What roles did Minnesota's Native American chiefs play? And who were some notable ones?

It is a well-known image: A stoic Native American man in ceremonial garb with a feathered headdress. A chief.

That portrait of strength and courage has been memorialized in films and statues, as well as exploited to sell cigarettes and motorcycles. It is a core American cultural stereotype, recently at the center of the most-watched sporting event in American history when the Kansas City Chiefs won Super Bowl LVIII.

Rob Robertson, a history buff from Eden Prairie, wanted to know more about Minnesota's chiefs and their roles. He wrote to Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reader-driven reporting project.

I am an enrolled member of the White Earth Nation here in Minnesota. I grew up on the White Earth reservation, and developed pride in my community and the land partly through hearing about these leaders. They felt real and tangible. But there are many misconceptions about Native American chiefs.

These people were leaders, but not like monarchs. Some communities had several chiefs. Many fought for their status, but also had a fragile hold on power. They often had an uncomfortable role bargaining and representing tribal interests to white colonizers — which sometimes left them ostracized from their own communities. Being a chief meant making tough decisions that others might not agree with.

What is a chief?

Anton Treuer, a professor of Ojibwe at Bemidji State University and the author of numerous books on Native Americans, said even the term "chief" is misleading.

"The word 'chief' is an English word and each tribe had its own words for different kinds of leaders," Treuer said. "I think there's a lot of confusion and stereotypes about what and who Native leaders were."

Some chiefs oversaw social functions, while others led people into battle. Fur traders in the region that became Minnesota would call Ojibwe people who represented their community a "village chief," Treuer said.

"But that was not the person who led people to war or the person who led ceremonies," he added.

Historically, chiefs followed hereditary lines, like European monarchies. But by the 19th century, this system was being usurped by some leaders — especially among the Ojibwe people — who came from common stock and pushed their way to leadership by charisma and force of will.

These chiefs led by consensus, persuading their fellow community members to work toward a common goal. For Native communities, leaders were only as good as their argument to action. They could easily fall out of favor.

Native American chiefs were not typically rich. Often, chiefs were materially poor and willing to give away what they had for the betterment of their communities.

There were parallels to European leaders, of course. Bravery was exalted. And many Native American chiefs were known for their reckless behavior on the battlefield and flamboyant appearance in public.

Little Crow

Taoyateduta, known as Little Crow, was a leader of the Mdewakanton Band of Dakota. By the early 1860s, the tribe was living in poverty on a strip of land along the Minnesota River. Treaties with the U.S. government promised them payments that never materialized. Little Crow was selected to speak for the rest of the tribe — and became known as a "chief" because of that leadership.

"He was ... restless and active, intelligent, of strong personality [and] of great physical vigor and vainly confident of his own superiority and that of his people," wrote Asa W. Daniels, a physician who worked with Native people in the mid-1800s. "He was affable and always self-possessed."

Negotiating with white people could bring dilemmas, including creating divisions among Native groups.

"Chiefs who accepted the advice of whites and incorporated them became dependent upon these new kinsmen to act in the best interest of the Sioux people," historian Gary Anderson wrote in the book, "Little Crow: Spokesman for the Sioux."

Little Crow was caught in the chain of events that led to the 1862 U.S.-Dakota War. He tried to calm the Dakota people who were starving and desperate, but found himself at the forefront of the conflict when it exploded into open warfare against white settlers. It is well documented that Little Crow did not initiate the uprising, but he did expand the conflict once it began.

The war with the U.S. government led to the eventual banishment of the majority of Dakota people from Minnesota.

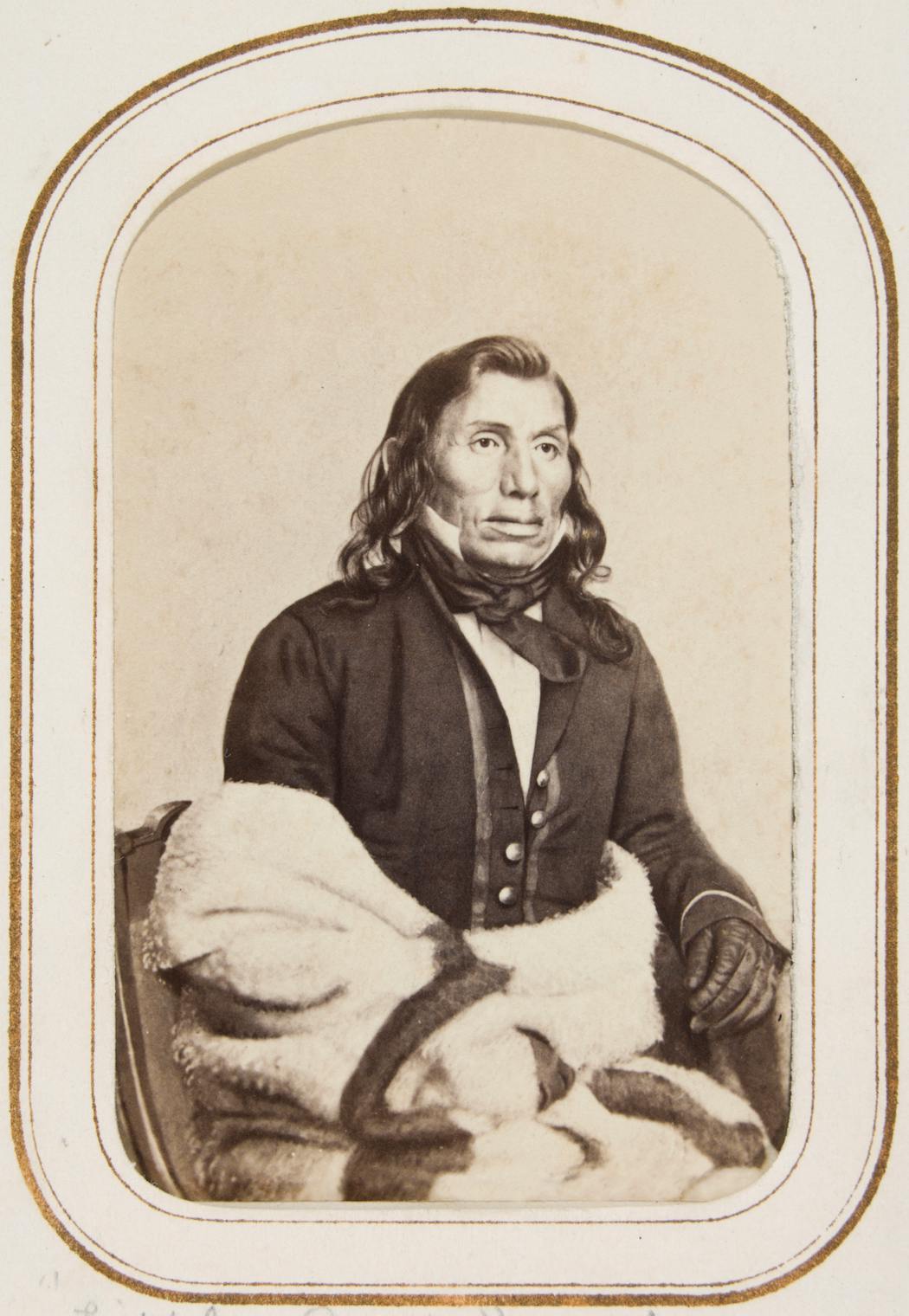

Wabasha

Tahtapesaah, known as Chief Wabasha, was also caught in the U.S.-Dakota war. He joined a group of Dakota who called themselves the Peace Party. The aim of the group was to bring people to safety during the chaotic conflict.

Despite his commitment to a peaceful outcome and the preservation of life, the U.S. government nonetheless exiled him to South Dakota and, later, Santee, Neb., according to the Minnesota Historical Society. The city and county of Wabasha are named after him and his ancestors.

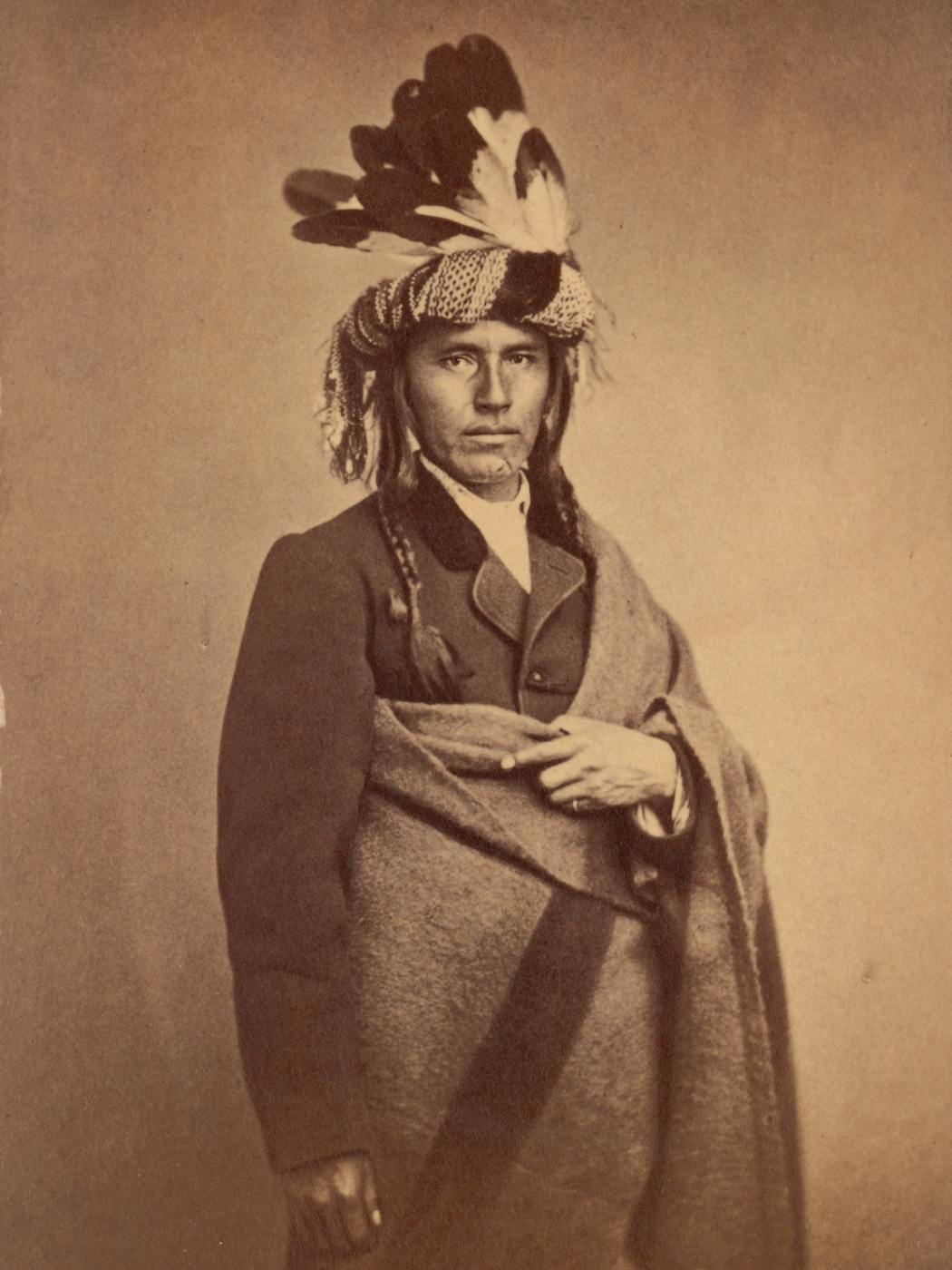

The Hole-in-the-Days

Several prominent Ojibwe chiefs shared the name Bagone-giizhig, or Hole-in-the-Day. Hole-in-the-Day the Elder, born in 1800, carved a new path to leadership through charisma rather than the old hereditary system. He led war parties against the Dakota in brutal battles for territory and influence.

"[H]e molded the minds of his admirers and adherents as he desired," wrote missionary Alfred Brunson.

His son, Hole-in-the-Day the Younger, was a brash and courageous leader like his father. His leadership led to divisions among the Ojibwe, culminating with his assassination at the hands of a group of Leech Lake Pillager Ojibwe. His killers held him responsible for the plight of all Minnesota Ojibwe and his controversial stance on who should go to the White Earth Reservation. It was later revealed that the assassins were hired by Charles Ruffee, a white Indian agent, and Clement Beaulieu, a mixed-blood trader.

The Hole-in-the-Days "had to lead in extremely stressful times when there was tremendous pressure on their people," Treuer said, "and the future of Native lands, leadership, and livelihoods were all in jeopardy."

There were other Ojibwes called Hole-in-the-Day, too. Probably the most famous was Ogima Bagone-giizhig, who led a skirmish against the U.S. Army on the Leech Lake Indian Reservation in 1898. The battle resulted in seven dead white soldiers and civilians. Some consider it the last chapter in the long and brutal conflicts between the tribes and whites moving into the American frontier in the 19th century.

Female chiefs

Not all of Minnesota's chiefs were men.

Ruth Flatmouth assumed the position of her brother, the Leech Lake hereditary chief Flat Mouth, while he was traveling. That continued after his death, and Ruth served as proxy at several significant diplomatic events, according to Treuer.

Female leaders, though rare, were not confined to religious or civil matters. Ogimaakwe, a female warrior at Turtle Mountain (in what is now North Dakota), also led war parties, Treuer said.

Modern chiefs

Today, Native communities have ceremonial drum chiefs and lodge chiefs who are recognized for spiritual ceremonies like naming newborn children and recognizing marriages. And the Red Lake Indian Reservation has civil chiefs overseeing some operations, several of whom are recognized by the tribal government, Treuer said.

"Most political positions are now elected," Treuer said. "But it's not uncommon for elected officials to be directly descended from hereditary chiefs."

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

How did Minnesota's indigenous people survive the extreme winters?

Which Indigenous tribes first called Minnesota home?

What does 'Minnesota' mean and how did the state get its name?

The voyageurs helped power Minnesota's historic fur trade. Who were they?

How many Native American boarding schools were there in Minnesota?

Minnesota's state seal and flag are changing. How was this controversial image created?