The voyageurs helped power Minnesota's historic fur trade. Who were they?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

Boisterous, bearded and clad in buckskin, sashes, feathered caps and beaded bags, they chanted in canoes by day as they skimmed across lakes and rivers in pursuit of fur, and by night danced and sang around campfires in the primeval woods encircling the Great Lakes.

These were the French-Canadian voyageurs of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, who left an impression on a region often more associated with its stern Scandinavian and German settlers.

In fact, voyageurs were some of the first Europeans to actually mingle with and marry into the area's long-established Native tribes. The Métis, an Indigenous people of southern Canada, are of mixed native and French ancestry.

And you don't have to look hard for signs of the legacy of the voyageurs around Minnesota. There's Voyageurs National Park along the U.S.-Canadian border. There's the 20-foot-tall "Pierre the Voyageur" statue in Two Harbors, and a 15-foot-tall companion along Crane Lake in the Kabetogama State Forest. There's the many voyageur-themed small businesses: a brewery in Grand Marais, a bus company in Duluth, even a Republican fundraising firm in St. Paul, to name a few.

"Who were the voyageurs?" Anne Stohr of Minneapolis wrote to Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reader-driven reporting project. "What brought them, what was their culture? What is known of their long-term impact upon the region in which Minnesota lies?"

"Voyageur" means "traveler" in French. The voyageurs are often conflated with the fur traders who drove much of the early European exploration of the Great Lakes, in search of the pelts of beavers, muskrats, bears, fox, lynx, otters and other mammals to sell as luxury items back home. In exchange, the tribes with experience in animal trapping got European-made goods: rifles, iron tools, cured tobacco, alcohol and other items.

Furs "were super sought after in Europe at that time," said Stephen Hausmann, an assistant professor of history at the University of St. Thomas. The voyageurs weren't driving the trade, but they provided the manpower that made it possible.

"They were the laborers," said Jacob Jurss, a visiting assistant professor of Indigenous history at Macalester College. "They're the ones out in the canoes paddling 14 hours a day or longer."

They hailed mostly from French settlements around Montreal and Quebec City. Most were "from impoverished backgrounds" and "saw a couple of tours on the waterways as a path to a better life," according to Minnesota writer Jon Lurie, who has researched the fur trade.

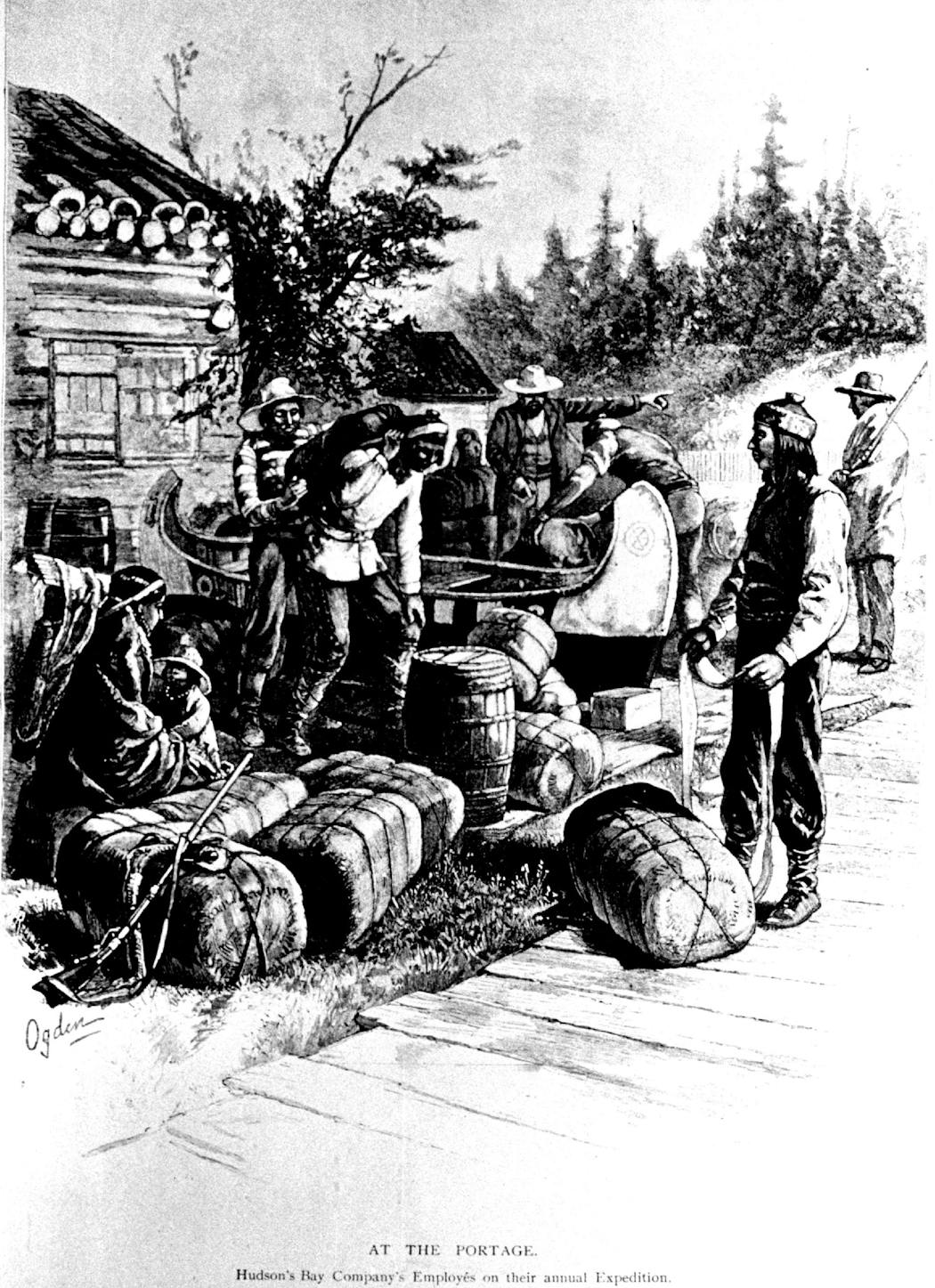

Recruited by several powerful corporations, the most well-known being the Hudson's Bay Company, voyageurs set out west for months or years at a time. Almost always short men — the better to fit in a canoe — they subsisted on rations of pork, nixtamalized corn and, well, whatever else was around. "A beaver's tail was considered an especially dainty morsel," Grace Lee Nute wrote in "The Voyageur," first published in 1931.

As they traversed the Great Lakes, voyageurs built knowledge of waterways and portages, and forged relationships with tribal nations. In Minnesota, that was primarily the Ojibwe and the Dakota.

"There would not have been a fur trade without the Ojibwe and Dakota people," said Katrina Phillips, an associate professor of history at Macalester and an enrolled member of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. "A lot of these voyageurs married Native women, and these kinship networks helped them find success in the fur trade. These nations knew the best ways to travel. It was Native knowledge, experience and expertise that undergirded the fur trade."

In fact, canoes were a Native invention. "Without the birchbark canoe the history of inland North America would have been altogether different from that which is on record," wrote Nute, who was a curator at the Minnesota Historical Society.

Phillips said it's possible to recognize the contribution and culture of the voyageurs — she likes to think of them as a sort of cowboy of the canoe — while still honoring the centrality of the tribes that were here first.

"To me you're not denigrating the voyageurs by recognizing this all started with the Native nations," Phillips said. "For me, it's more about creating a richer narrative."

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

How lumberjacks harnessed an 'ocean of pine' to build Minnesota?

Why has the Park Board allowed the 'birthplace of Minneapolis' to deteriorate?

Why did Scandinavian immigrants choose Minnesota?

Is Minnesota actually more German than Scandinavian?

How did early settlers survive their first Minnesota winters?