How did Northfield become home to St. Olaf and Carleton colleges?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Apple Podcasts | Spotify

Minnesota boasts many college towns. But Northfield is unique.

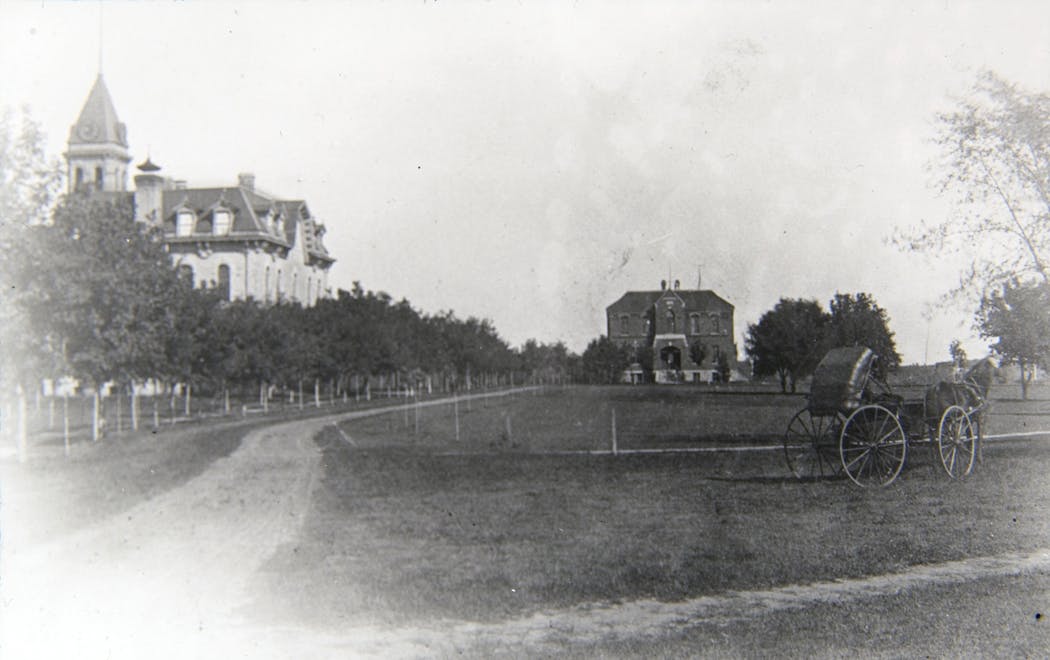

Located just beyond the Twin Cities' southern exurbs, Northfield is home to two prominent private colleges — St. Olaf and Carleton. Those institutions have shaped the city from a historical milling hub into an education-focused rural center.

Darrell Swanson, a 1970 St. Olaf graduate, regretted leaving Northfield after he got his degree. After recently reminiscing about his time there, the Pequot Lakes resident asked Curious Minnesota — the Star Tribune's reader-driven reporting project — how Northfield became home to Carleton and St. Olaf.

"Why would there be these two liberal arts schools founded in the 1800s in Northfield, Minnesota, of all places?" he asked.

The short answer: Religion.

Religious groups across the U.S. were largely responsible for founding private colleges and universities in the 1800s, in part because there were no set college plans or direction from the federal government, according to Tom Williamson, an anthropology and sociology professor at St. Olaf College. Northfield's colleges grew out of a camaraderie among Congregationalists and Lutherans who settled in the town.

That cooperation has given the city outsized stature. Alumni of the colleges include Supreme Court justices, governors and senators, as well as Pulitzer Prize and Oscar winners. And Northfield attracts a fair amount of visiting dignitaries for a small city of 20,000.

Northfield's religious origins

A treaty between the federal government and the Dakota people in 1851 opened up much of southeastern Minnesota to white settlement. Settlers raced to grab land and founded towns shortly after.

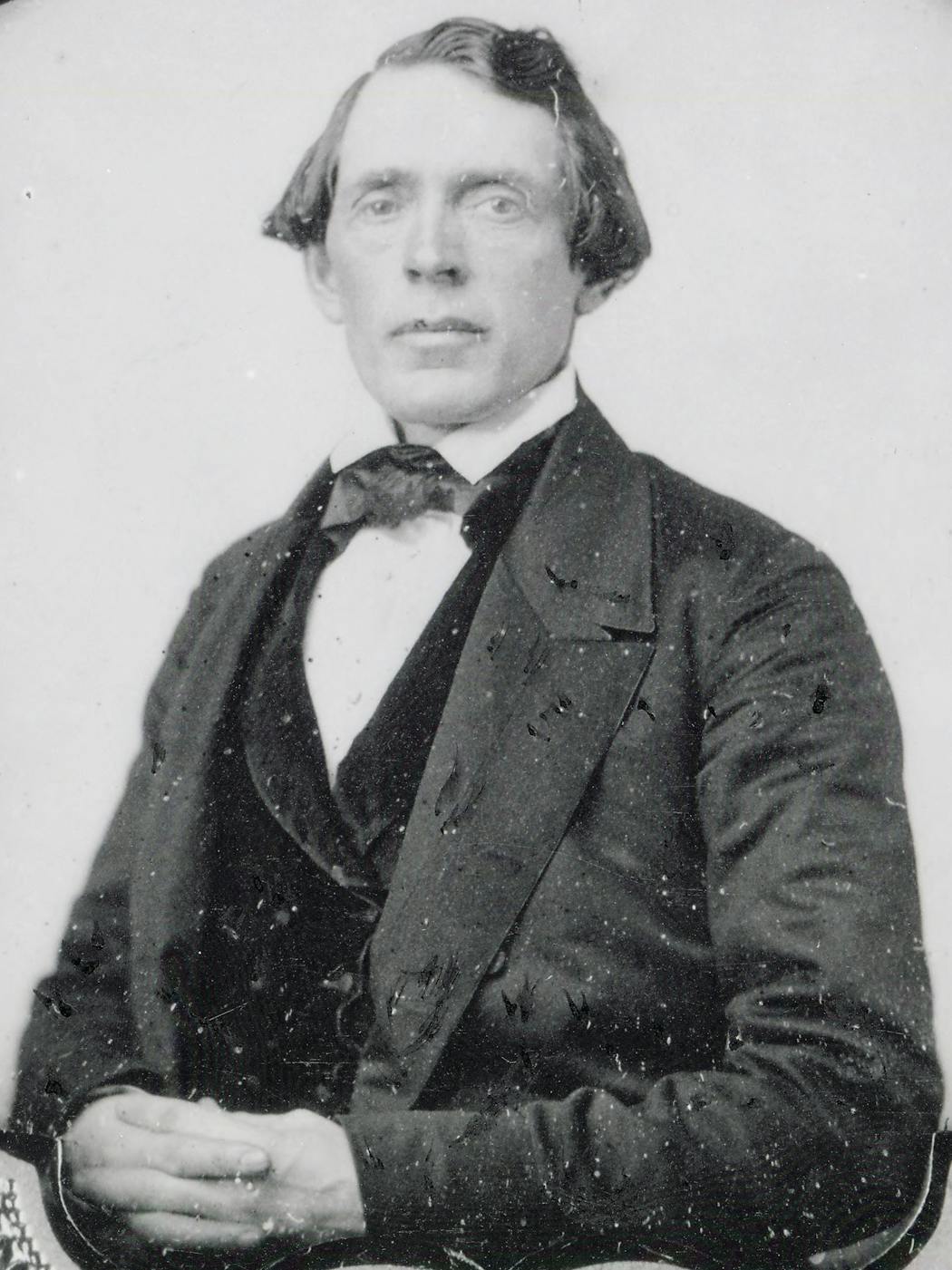

Among them was New York lawyer and abolitionist John North. He took a trip south from St. Anthony in 1855 to look at land along the Cannon River Valley, planning to harness the river's flow to power new saw and grist mills. That same year, North gathered other settlers from New England in the area and platted Northfield.

North had designs for a college there, according to archivists at Carleton and St. Olaf. The idea didn't gain traction, however, until the General Conference of Congregational Churches in Minnesota chose the city to build a school in 1864.

The conference of independent churches descended from New England Puritan churches. They had looked at multiple cities across the state for their school, including other southeast Minnesota towns such as Zumbrota and Mantorville, according to Tom Lamb, an archivist at Carleton College.

But Northfield was a growing burg, connected to St. Paul along the railroad in 1865. It also didn't hurt that the city had the second-largest Congregationalist population in the state behind Minneapolis.

That was by design, according to Sean Allen of the Northfield Historical Society. North and his neighbors shared similar views on ending slavery and the evils of alcohol, so they chose to create Northfield rather than settle in nearby places with bars or liquor stores.

"It was generally considered to be a dry town," Allen said.

The new school, Northfield College, evolved over time. It began as a preparatory program in 1867, with the first college students enrolling in 1870. The college was renamed Carleton College after a $50,000 donation by Massachusetts manufacturer William Carleton, which saved the institution from the brink of financial collapse.

Soon, Norwegian farmers and pastors in the community sought a college of their own. Congregationalists in town welcomed the effort. Carleton officials even helped their Lutheran counterparts found St. Olaf College in 1874.

From there, the two schools blossomed during the higher education boom in the 1880s through the 1920s. Colleges and universities in that era began offering specialized programs and enrollment across the country skyrocketed.

St. Olaf kept its reputation as a Lutheran school aligned with its heritage — the school was named after an 11th century Norwegian king who spread Christianity. The school also remains a dry institution.

Carleton shed its religious identity in the 1960s, doing away with requirements to attend chapel after a group of students jokingly formed their own druidic society to skirt the rules.

"That was a big period of transition," Lamb said.

An intense rivalry

The schools have largely helped one another over the years — they share library catalogs, among other resources. Their sports rivalry hasn't been quite as cordial over the decades, even becoming bloody at times.

There would be downtown brawls in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s whenever the colleges played each other, often stemming from the tradition where students would turn an eagle statue on Bridge Square to face the winning college, Lamb said.

Homecoming weeks were tough for both colleges. Freshmen would try to light the other school's bonfire the night before it was set to be lit, often running into student guards who would catch them and shave their heads. Williamson's father, a fellow St. Olaf grad, had his head shaved during his freshman year.

Things escalated to the point both schools had to sign a "peace treaty" in 1951, vowing to tone down their rivalry. Their competitive spirit took a slightly nerdy turn in 1977, when the two schools played the first game of metric football among U.S. colleges.

Northfield today

The colleges form the backbone of Northfield today. About three out of every 10 residents are students or faculty, according to each college's records. The colleges help fuel the area's vitality, but their dominance has its downsides.

Both schools continue to buy land for future growth. Yet Northfield also has become a draw for seniors looking to enjoy the vibrant college community in retirement. These factors have driven up home values and resulted in fewer housing options for would-be residents. Allen said many professors commute from the Twin Cities.

Aside from a Post cereal factory, there aren't many large industrial employers in town where college students can start their careers.

"We just don't have as much as a city our size needs to have, and so it's something I know the city has been trying to improve on," Allen said.

At the same time, Northfield arguably wouldn't have grown without Carleton and St. Olaf drawing people to the area.

"I don't know of any other small town ... that would have two institutions like this," Lamb said. "It is kind of a unique setup."

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

The Jolly Green Giant has moved on from Minnesota. So who is maintaining his iconic billboard?

Why is it so much harder for U students to graduate debt free compared to the '60s?

Why did Scandinavian immigrants choose Minnesota?

How St. Cloud nearly became a car manufacturing hub

How were the bluffs of southeast Minnesota formed?

Did political shenanigans derail an effort to move Minnesota's capital from St. Paul?

Correction: Previous versions of this article erroneously said that Carleton and St. Olaf colleges do not pay property taxes.