How important was the Iron Range to winning World War II?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

DULUTH — Minnesota nearly depleted its immense supply of high-grade iron ore to help the Allies win World War II, providing much of the crucial raw material behind America's tanks, warships, guns and ammunition.

Reader Jim Herzog wanted to know just how much the Mesabi Range mines contributed to the "arsenal of democracy." He sought answers from Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reader-powered reporting project.

The short answer is that Minnesota's rich iron deposits were a vital component of America's war effort. About 70% of the iron ore that America devoted to the war came from Minnesota, amounting to more than 333 million tons, according to Pam Brunfelt, a retired Vermilion Community College faculty member and historian.

"Without the Iron Range, we would not have won the war," said the Britt, Minn., native, who is writing a book about the phenomenon. "It was just the most astonishing accomplishment."

Steel production in America tripled from 1938 to 1943. In 1942 alone, America produced about 8,000 warships, 24,000 tanks, 48,000 military airplanes and 667,000 machine guns, according to Marvin G. Lamppa's "Minnesota's Iron Country." Much of the raw material to make those armaments came from the Iron Range.

The country's need for all that natural iron ore during the war almost depleted Minnesota's deposits and led to the mining of taconite, the lower-grade mineral produced on the Range today to make steel.

A breathtaking pace

The rich deposits of the Cuyuna, Mesabi and Vermilion ranges formed more than 2 billion years ago when iron eroded from mountains into an inland sea that covered the Arrowhead region. It was eventually exposed to oxygen and formed layers of compacted iron sediment.

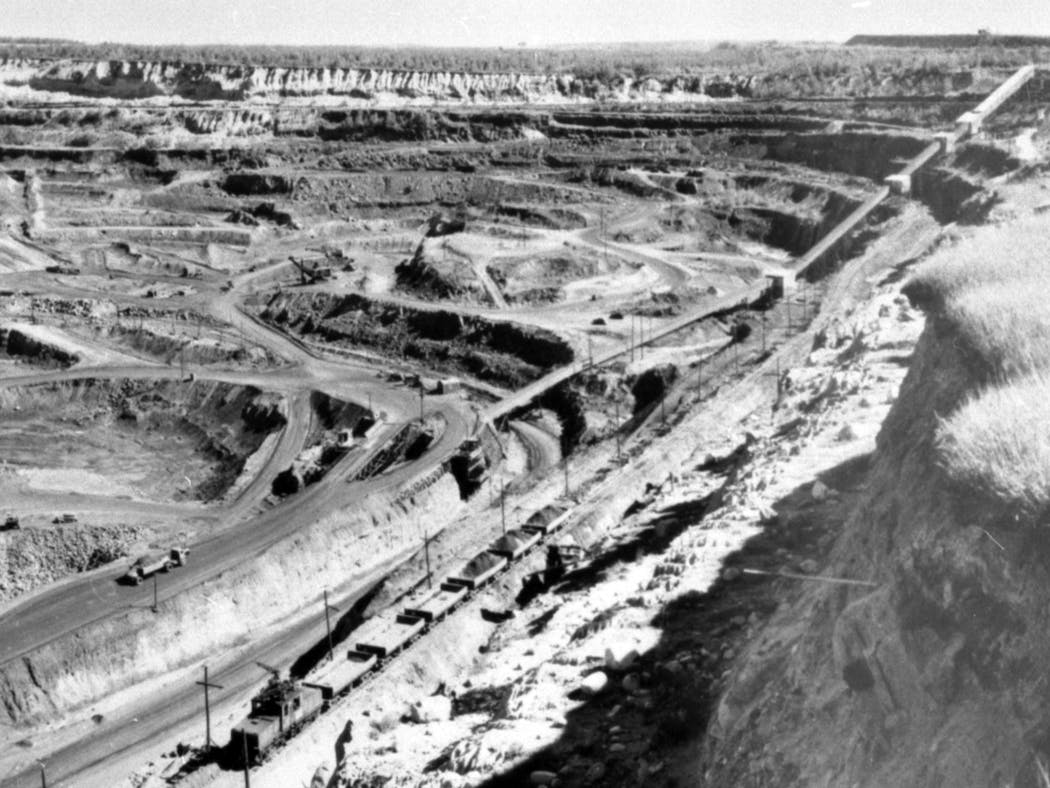

Minnesota's Iron Range featured the top iron ore-producing mines in the nation in the early 20th century, helping to build structures like the Empire State Building. The area was keenly positioned to lead the way during the war in iron production, with fully equipped open-pit mines that could ship material easily via a railroad system and docks at Two Harbors and the Twin Ports.

"The infrastructure was there to make it happen," said Ron Hein, a retired Erie Mining executive who co-authored the book "Taconite: New Life for Minnesota's Iron Range, the history of Erie Mining Company." "We had the raw material and manufacturing base to convert from peacetime manufacturing to war time manufacturing."

The great need for labor and military personnel led Iron Range women to enlist in war efforts once they were authorized by Congress, as well as work in the mines for the first time.

Mining companies opened new mines and expanded existing ones, in some cases excavating more than 100 feet below ground to reach ore. The Mesabi's oldest mine in Mountain Iron, which had become a lake by 1943, was even drained and reopened.

Wartime propaganda touted the importance of the Range. A 1943 Great Northern Railway magazine ad, for example, declared the region and its iron "more vital than gold" to winning the war.

In one 24-hour period in August 1943, more than 120,000 tons of ore were loaded onto 245 trains headed east to the hearths and blast furnaces of steel mills, Brunfelt said. Empty and loaded trains traveled in and out of the Hull-Rust-Mahoning pit in Hibbing every three minutes.

Miners and dock workers raced to keep up with the breathtaking pace, sometimes laboring around the clock even through winter months.

The Minneapolis Star wrote in 1943 that thousands were working through "sub-zero cold and driving snows, day and night ... preparing for the greatest movement of iron ore that man has torn from the earth in one year in all human history."

These efforts broke iron ore shipment records for the entire Lake Superior region in 1941 and 1942, according to a 1943 issue of Skillings Mining Review, printed in Duluth.

"Certainly the 1942 record of shipments was an achievement that was undreamed of a few years ago," the story read, citing more than 93 million tons moved by ship and rail that year.

It was 19,000 times what was produced in the Range's first year, five decades previous. But that total would not be topped again.

A depleted resource

Stakeholders knew that high-grade iron ore on the Range was finite. But many were confident supply would withstand the war.

"Mr. Hitler is wasting his time. The marvelous little Mesabi makes it impossible for him to win," mining booster Arthur Dudley Gillett said in 1943, according to the book "Minnesota Goes to War" by Dave Kenney.

But when the war ended, "the rusting wreckage of steel formed from Iron Country's mines lay strewn across the planet — smashed and broken tanks, trucks, ships, guns. ... And most of Minnesota's natural iron ores were gone," Lamppa wrote.

Brunfelt's father and grandfathers were miners. She recalls hearing worries about the eventual depletion of iron ore and what that would mean for the future of Iron Range communities.

"Taconite turned that around," she said.

Indeed, research on how to extract and process low-grade iron ore — taconite — had been underway for years, spearheaded by Edward W. Davis, a University of Minnesota professor. New technology led to steel companies building taconite mines and mills in the 1950s and 1960s.

People at the time believed that taconite had saved the Iron Range, Jeffrey T. Manuel wrote in "Taconite Dreams."

But it had consequences, he wrote, including the closure of mines that couldn't compete and years of environmental pollution from tailings dumped into Lake Superior. That resulted in a blockbuster lawsuit against Reserve Mining Company in the 1970s.

The Iron Range's mining industry is smaller today. Some empty mines have been reclaimed for new use, such as the Redhead Mountain Bike Park in Chisholm. Redhead Mountain is a 25-mile trail that travels through the rugged red earth along open pits filled with water.

Mining on the Mesabi Range remains a big part of the United States' story, said Jordan Metsa, a spokesman for Chisholm's Minnesota Discovery Center. It continues to support the global economy, he said, but its past — both in helping to build the country and in aiding war efforts — deserves more recognition.

"Forty-three different ethnicities came to the Range to mine the ore," he said. "The work they did to win World War II gives me goosebumps. It is one of the most underestimated stories in America."

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

What did the topography of the Iron Range look like before it was mined?

Was Duluth once home to more millionaires per capita than any other U.S. city?

Is Duluth the most inland seaport in North America?

How much gold is hiding underground in northern Minnesota?

Historic wildfires once destroyed entire cities in northern Minnesota. Could it happen again?

Why is the BWCA a wilderness and not a national park?