What did the topography of the Iron Range look like before it was mined?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

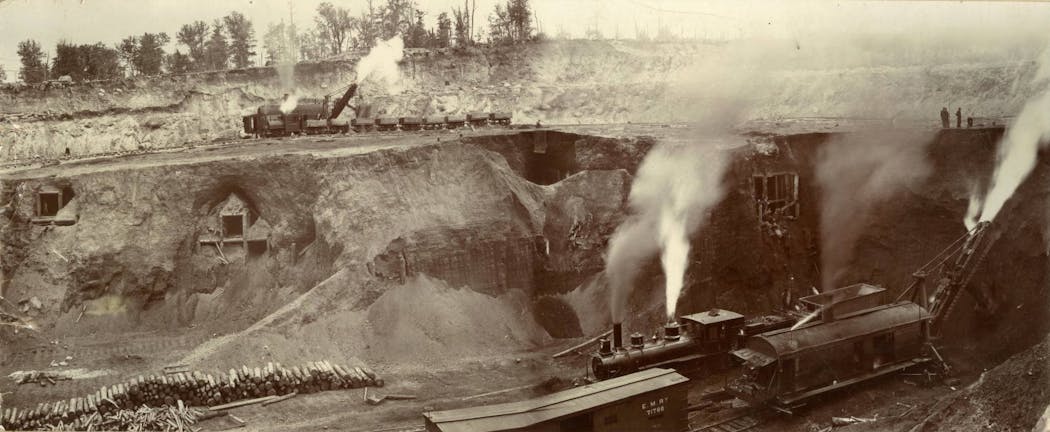

DULUTH - Scanning the vast horizon from Hibbing's Hull Rust Mine View can feel like a trip to another planet. From the air, too, the stretch of iron mines is hard to miss: Enormous pits dot the 100-mile ribbon of the Mesabi formation that takes its name from the Ojibwe word for "giant."

The open-pit mines that now account for nearly all U.S. iron ore production have unquestionably transformed the landscape of northern Minnesota. So one anonymous reader wanted to know: What did the Iron Range look like before mining?

As part of the Star Tribune's series fueled by great reader questions, Curious Minnesota, we took a deep geological dive to find the answer.

Let's start roughly 2 billion years ago.

Life on Earth was just beginning to proliferate at a rapid pace, leading to a lot more oxygen in the air and the oceans. This caused the iron in the shallow sea that covered Minnesota at the time to form a layer that settled under layers of silt. This happened around the world, creating similar iron deposits in Australia, Brazil, China and elsewhere.

Odds are, that won't happen again.

"We're not going to experience something like that again in our geologic history, and that happened billions of years ago," said Heather Arends, mineral potential manager with the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. "That was preserved through tectonic history for the next billion years and is preserved in our landscape in these deposits."

In more recent geological history, about 2 million years ago, the Iron Range began to resemble a tundra, with woolly mammoths and saber-tooth tigers roaming the vast Mammoth Steppe that spanned the globe's northern latitudes. The advance and retreat of the glaciers did not disturb the bands of iron, but they did create the conditions for the modern boreal forest that eventually became home to generations of the region's Indigenous residents.

The shape of the Mesabi Iron Range, which cuts a diagonal band across northeastern Minnesota, has been shaped by a bedrock formation called Pokegama Quartzite that served as a "speed bump" for glaciers, Arends said.

"If you think of the Iron Range being a ribbon running east-west across the landscape with a crease in the middle, the Pokegama Quartzite is exposed on the very north side of the feature and dips south underneath the iron formation," she said.

The Mesabi Iron Range is the largest of Minnesota's three major iron formations, which also include the Vermilion Range near Ely and the Cuyuna Range near Brainerd — both of which are now inactive. When folks talk about "the Iron Range," they are usually referring to the Mesabi, which stretches from Grand Rapids to beyond Virginia.

By 1892, when large-scale mining started scooping that two-billion-year-old iron out of the ground, the natural features of northern Minnesota looked much as they do today. But now there are massive pits and mounds of waste-rock stockpiles spread across the Iron Range.

Up close, that has left an otherworldly imprint on the landscape. Parts of Hibbing were once moved to make room for the ever-expanding Hull-Rust-Mahoning mine that is now six square miles and more than 500 feet deep in parts. Hills on the edge of the mine were created from mine tailings; such deposits are especially noticeable when driving into Virginia on Hwy. 53 and in some cases are 200 feet tall.

Viewed from afar, and from a geologic lens, the changes are less dramatic — if the goal is to picture what it looked like before 1892.

"With in-pit mining, the major original topography is still preserved," Arends said.

Despite billions of tons of ore and other rock being removed over the past 130 years, Arends said it's not too hard to imagine what the region looked like before those pits and stockpiles started growing to their current size. That's due to the relatively flat topography of the Range and the lack of mountaintop-removal mining that has more drastically transformed other mining regions.

In Appalachia, for example, hundreds of mountains have been blasted away for coal mining, which has had spillover affects on nearby streams and wildlife.

"Other mines operate in more mountainous regions, where you have thousands of feet of (elevation) versus maybe hundreds here over many miles," said Larry Zanko, senior research program manager at the Natural Resources Research Institute in Duluth.

"Two billion years ago, the topography of the Iron Range looked a lot different. But today it's fairly flat," he said, referring to the modern era. "It's not like the Rockies."

The short answer to our reader question? Squint at a satellite image of the Iron Range, or zoom out enough so the features start to blur. There you can piece together the look of the region just before mineral extraction started to reshape the land, its people and the world.

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

How much gold is hiding underground in northern Minnesota?

Is Duluth the most inland seaport in North America?

Why is the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame located in tiny Eveleth, Minnesota?

What is the best place, time to see northern lights in Minnesota?

Why is Minnesota the only mainland state with an abundance of wolves?

When did wild bison disappear from Minnesota?

Correction: This story has been updated to clarify the location of the Mesabi Iron Range.