Times are tough in Zimbabwe. President Robert Mugabe has caused economic collapse in thevery nation he helped found. Unemployment is 10 times greater than in the United States. There are not enough zeros toaccurately reflect the hyperinflation that now makes the notion of buying aloaf of bread with a wheelbarrow full of currency seem like a good value.Poverty, malnutrition and hunger are widespread in a nation that was onceconsidered the breadbasket of the continent. Throw in the human rightsviolations that are occurring in Zimbabweand you have another African nation on the road to failed state status.

Even in the best of times in Zimbabwe,however, things would have been tough for a young person named Tawanda. As achild, Tawanda was the apple of his father's eye. Tawanda was born in a growthpoint (an underdeveloped rural village on communal land) 200 kilometers northof the capital city, Harare. At theage of 12 Tawanda says that "I started being me." It was at that point that thefather's affection for Tawanda began to diminish as it became apparent to thefather, and others in the growth point, that although Tawanda was born agenetic male; he identified as a female. (From this point forward I will referto Tawanda as a she.)

Year after year, as social conditions worsened in Zimbabwe,things also got worse for Tawanda. The name calling she endured at the age of13, turned into rocks being thrown at her at 14, and beatings later. Tawandacould no longer safely attend school so her mother home schooled her, butTawanda fell behind in her education.

Earlier in his presidency Robert Mugabe referred tohomosexuality as "sub-animal behavior." In 2006, when Tawanda was 16 and nolonger allowed to attend church because of how she looked and acted, Zimbabwepassed legislation that further criminalized homosexuality. Today, any actionsthat can be perceived as homosexual, such as two men holding hands or kissing,is a criminal offense. By this time rocks were being thrown through the windowsof Tawanda's home at night.

Fearing for her safety, and that of her family, Tawanda realizedshe needed to leave her country. Tawanda secured a visitor's visa and with onlythe clothes on her back, boarded a bus for Johannesburg, South Africa. She triedto keep her face hidden to avoid any possible harassment from fellow passengerson the two day journey. In Johannesburg,Tawanda read about a nonprofit that helped people like her in Cape Town and she found the money to take a local train tothe southernmost African city. From there she made it to iThemba Lam, anorganization in the township of Guguletuthat provides temporary shelter to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgenderedpeople who have nowhere else to go. By the time she arrived at the shelter,Tawanda was barefoot – her only pair of shoes having fallen apart.

For now, Tawanda can stay at the safe house. And she canlegally stay in South Africafor another seven weeks until her visa expires. Although to an outsiderTawanda's future seems as grim as that of Zimbabwe's,Tawanda, at the age of 19, does not see it that way.

"All my life" she says, "people told me to try to be normal.But this is normal for me. I always knew I would have a good life one day – notin Zimbabwe –but somewhere. Somewhere there is a good life for me."

(Postscript: Tawanda is a real person, but a fictitiousname. Out of concern for her parents in Zimbabwe,the subject requested that her actual name not be used.)

Former St. Kate's nursing dean embezzled $400K, charges say

Debate over whether to divest from Israel dominates University of Minnesota regents meeting

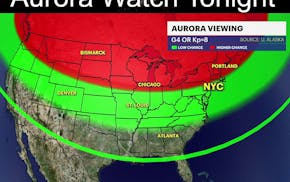

'Highly active' northern lights displays this weekend may be largest in nearly 20 years

Neal: Hurt most by Bally-Comcast fight? Superfans like Debbie