Erika Lee was sitting in a college history class when she first learned about a law that had barred Chinese people from coming to live in the U.S. That law was on the books for 60 years.

Lee, the granddaughter of Chinese immigrants, couldn't believe it. She had never heard this history — her history — before.

" 'Aha moment' doesn't even capture it," she said. "It was this jaw-dropping moment of shock because I am Chinese-American. My family has been in this country for generations. And I was a history major. I remember thinking, 'I never knew this happened.' "

She felt shock, anger and an urge to dig deeper.

"Then it translated into: Why?" she said. "Why haven't I ever learned about this? And what other stories are there? And who is writing this stuff? Maybe I should do it."

She did.

After graduating from Tufts University with a degree in history and cross-cultural studies, she earned a doctorate in history from the University of California, Berkeley.

Today, the soft-spoken 45-year-old professor is director of the renowned Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota, which promotes research on the lives of immigrants to the U.S.

She's also the author of three books about the Asian migration to America. Her latest — "The Making of Asian America: A History" — is epic and eye-opening.

We talked to Lee about the fastest-growing ethnic group in the country, and about what the Asian-American experience tells us about who we are as a nation of immigrants.

Q: You say that the history of Asian-Americans is also the history of how race works in America. How so?

A: One of the questions that I was trying to answer was: Why are Asian-Americans invisible in American history?

Typically when we think about race in America, we think about black and white. So Asian-Americans kind of slip through the cracks, along with Latinos and American Indians, as well.

I think it's [these] groups in the middle that often shift between being more considered like African-Americans or being more considered like whites that we can best understand how race is so complicated.

And that it really depends on what's going on in the country: the state of the economy, Americans' confidence in society, our international relations, whether we're at war, what's the state of African-American civil rights.

Q: Can you give an example?

A: In the late 19th century up through World War II, historians have argued that Asian-Americans were more seen like African-Americans, but that during World War II and the Cold War and since then, there's been a dramatic shift in perception in relation to Asian-Americans. Now they're seen as "model minorities." Maybe even honorary whites. Maybe even outperforming whites, which can be a threat itself.

Q: How do you see Asian-Americans?

A: I think of Asian-Americans today occupying this really interesting, but also fragile, place of being celebrated, accepted, but still vulnerable.

Q: With so many different countries of origin and religions making up the Asian-American community, can there really be one Asian-American history?

A: Yes and no.

There are 24 different groups. And most would find very little in common with each other. It's more of a second- and perhaps third- and later generation that understands and embraces this pan-ethnic label.

One of the reasons why this label even came to be — it is a creation of Asian-Americans themselves in the 1960s — was to foster unity and coalition-building. The idea is that together, we can be more unified and lobby and advocate on common issues.

[The Asian-American label] still has some use, and I think it's growing as an identity. But it also doesn't encapsulate everything, that's for sure.

Q: What lessons from the history of Asian immigration to the U.S. can be applied to today's immigration debate?

A: We have debated immigration before, and we have passed some egregious laws that we later apologized for. We've done it before and we've realized our mistake. So the question is: Do we want to do it again?

Q: What mistakes did we make?

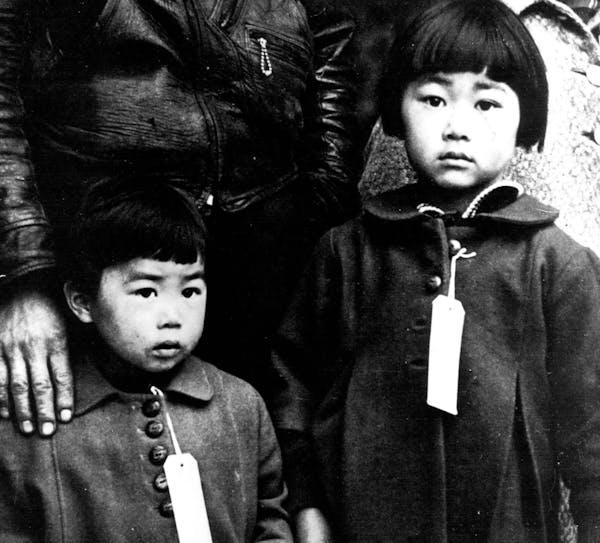

A: The Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred generations of Chinese from coming [to the United States], helped to promote a multinational business in undocumented immigration because there was still demand [for workers] but the gates were closed. It helped to ensure that generations of Chinese-Americans — including U.S.-born citizens — lived in the shadows, and were not fully integrated into America.

When President [Franklin] Roosevelt signed the repeal of the exclusion laws, he called them a "historic mistake." In 2012, Congress passed a Statement of Regret, which talked about the injustice of the laws and its long-standing effects.

Some would argue that the new immigrants are different. They are much more of a problem. I would say go back to the historical record and see how Americans from every class, every background, talked about the Chinese, Japanese — the so-called model minorities today — as an immigrant invasion, unassimilable foreigners, a threat to American civilization, a threat to world civilization.

Then the argument that today's immigrants are so different and are such a bigger threat seems a little hollow.

Q: Who is this book for?

A: It's for the students whom I teach every semester, so that they don't have to say, 'I never knew that this happened.' So they can turn to this book and realize that their histories are also part of American history.

It's also for people interested in American history in general, so that they realize how important Asian-Americans have been always to the making of this country.

Allie Shah • 612-673-4488

Jerry Seinfeld's commitment to the bit

Chasing 'Twisters' and collaborating with 'tornado fanatic' Steven Spielberg