Minnesotans are about to host the greatest show on bentgrass.

We have the Vikings and Twins, the Wild and Wolves, the Lynx and Loons. We have a Big Ten athletic department, the MIAC, and as attractive an array of sports venues as you can find anywhere.

The Super Bowl and major college events are bound for new U.S. Bank Stadium. Baseball's All-Star Game recently visited Target Field. There is the possibility that a local team could even host a championship in the near future, if we can find a way to move the entire state off the million-mile burial ground that haunts Minnesota sports.

Minnesota has played host to a handful of golf majors, and the annual 3M Championship, and in one stretch during the '90s the Stanley Cup Final, the World Series, the Super Bowl, the U.S. Open, an NFL playoff and the arrival of an NBA team.

We do not lack for major sports activity, but Minnesota has never seen anything like the Ryder Cup, and likely never will again in any of our lifetimes.

The Super Bowl imposes itself on America, promoting itself as the temporary center of the universe. The World Series generates a Rockwellian sense of glee in each home ballpark.

The Final Four is the "all rims are 10 feet" speech from Hoosiers writ large. College football offers pageantry and the world's best marching bands. The Stanley Cup and NBA playoffs, shoehorned into arenas, prompt giddy claustrophobia, and golf's majors promote individual dramas strewn over the most beautiful spaces on earth.

None of those events is quite like a Ryder Cup.

The Ryder Cup should not be as entertaining and dramatic as it is. To paraphrase the old joke, the Ryder Cup is an international competition waged between a bunch of people who live in Orlando. That's part of its charm.

The Ryder Cup takes a couple dozen professional golfers who spend most of their time obsessed with swing thoughts, practice, money, sponsorships, money, majors and money, and changes the way their brains and hearts work for a week.

Every other championship offers a logical conclusion, a heightened version of a familiar game. The Super Bowl isn't necessarily better than the NFC Championship Game; it's just the next step.

The Ryder Cup is a departure. It alters the sport and the people who play it.

Most golf championships pit individuals looking out for their own self-interest in stroke play, which encourages conservative decision-making.

The Ryder Cup's match-play format, combined with jingoism, brings adrenaline to the first tee, and the first green. On Friday at Hazeltine, you will see golfers pumping up the crowd at the first tee instead of trying to calm their own nerves.

The Ryder Cup forces individualists to play for the greater good.

Europe's dominance of the event is painful for American golf but instructive. The Americans usually have a perceived talent advantage but lose to Euros who seem more united.

In so many other sports, playing with emotion is a requirement, or a stratagem. At the Ryder Cup it is a reaction to nerves and fear.

Golfers who have won majors say they've never been so nervous as on the first tee of a Ryder Cup. The competition has made heroes of Sergio Garcia, Lee Westwood and Ian Poulter, who have never won majors yet play like champions in Ryder Cups.

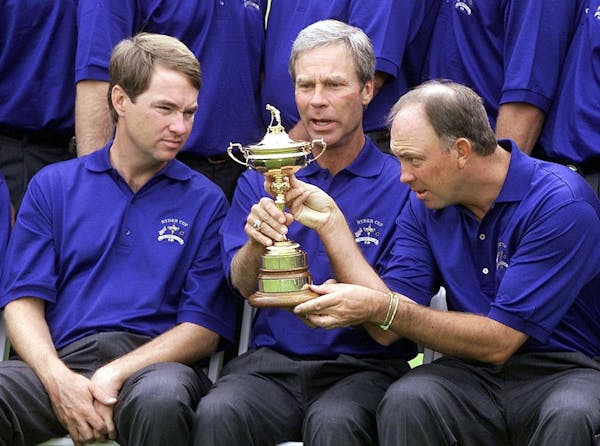

One of my favorite moments in Ryder Cup history was not pivotal or even important. Minnesotan Tom Lehman was playing for the American side at Valderrama in 1997. Lehman's temperament reflects his home state. He is understated, polite.

Lehman holed a long, difficult, brilliant chip to win a hole, and then Our Guy leaped in the air, shaking his fist as he ran toward the green.

It was not choreographed. It could not have been choreographed. No one would have thought to combine those movements. Lehman's reaction spoke of joy, and relief.

We'll see a lot of that at Hazeltine this week. There is nothing quite like the Ryder Cup, and there may never be another one in Minnesota. Enjoy.

Jim Souhan's podcast can be heard at MalePatternPodcasts.com. On Twitter: @SouhanStrib. • jsouhan@startribune.com

Souhan: These seven plays showcase Wolves' new defensive fire

Souhan: Wolves fans made Game 1 special. Now bring on Game 2.

Souhan: Should Vikings even consider McCarthy in NFL draft?

Souhan: NAW erases Suns' lead, Game 1 advantage with big performance