To figure out just how loud some local restaurants are, I enlisted the man who has created the world's quietest room: Steve Orfield. As president of Orfield Laboratories, which analyzes acoustics, he has extensive experience with restaurants.

For Bill and Steve's Excellent Auditory Adventure, we headed to Minneapolis' North Loop, home to several popular eateries, most of which have been carved out of warehouse spaces. With their wide open expanses, high ceilings and hard surfaces, they're a recipe for noise.

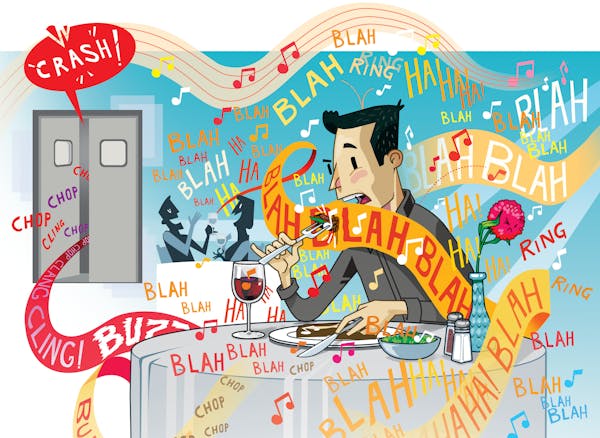

We were looking for what Orfield called "speech interference level," the point at which you have to raise your voice to be heard. Orfield was equipped with two small measuring devices: a real-time analyzer that measures full frequency range and decibel level (dB), and a precision sound-level meter that doesn't track fast noise changes but measures the average sound pressure level (dBA).

At Smack Shack, we got a table upstairs, where it seemed, at first, to be fairly quiet. Before long, the din from the music and the quickly filling tables had increased enough that we had to raise our voices. The average noise levels clocked in around 80 dBA, well above the normal talking level of 65 dBA.

We were dealing not only with music and other patrons talking but also reverb, Orfield said. "Because of reverb, the noise continues to last."

This is a bigger factor at places with high ceilings, like Smack Shack. "If the ceiling is twice as high, the reverb will be twice as high," he said.

Our next stop, Bar La Grassa, had a lower ceiling, but was just as noisy. From our perch at the pasta bar, we were farther away from the stereo speakers, but right next to the clamorous open kitchen. Most of the racket came from the crowd, which was predominantly under 40. "Older groups self-sort from venues that are difficult for them to use," said Orfield.

Next stop: Borough. While the volume was similar to our two previous stops, the music was louder here and the tall, room-ringing windows created dissonance. "People have to overtalk the music," Orfield said, "and before long everyone's talking louder. It's a ripple effect."

After Borough, we ducked into Black Sheep, which had at least a dozen people waiting for tables. The din, however, was more tolerable, in part because the lower-level space has low ceilings, Orfield said.

It was time for a break, and Sapor filled the bill. Lower ceilings, softer music and a smaller crowd comprising mostly couples made for a much quieter stop, at just under 70 dBA.

At the wide-open, sprawling Freehouse, though, the music was booming, if much less clear, what Orfield called "a low-frequency rumble."

"Right now, nobody would say that this was music," he said. "The louder the noise is, the more all you hear is the bass. The bass punches through everything."

To get better, clearer sound in restaurants, Orfield advocates smaller, higher-quality, strategically placed speakers rather than a few large thumpers.

I strained to hear him. He strained to talk. We'd been at this for hours. We were both happy to call it quits.

Bill Ward • 612-673-7643