How intercepted Soviet newscasts once fueled a hit show in the Twin Cities

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Apple Podcasts | Spotify

Editor's note: Alexey Voloshinov is a Russian journalist in exile who visited the Star Tribune's newsroom in September 2023. He had been practicing independent journalism inside Russia for the last six years, but the country's repression of journalists ultimately forced him to flee.

Residents of the Soviet Union once traveled far outside their cities, tuning their radios to pick up broadcasts of so-called "enemy voices" promoting life in the Western world, programs like Voice of America and Radio Liberty.

Little did they know that halfway around the world, Minnesotans were getting a glimpse of life in the U.S.S.R. thanks to an unusual show on public television: "Channel 3 Moscow."

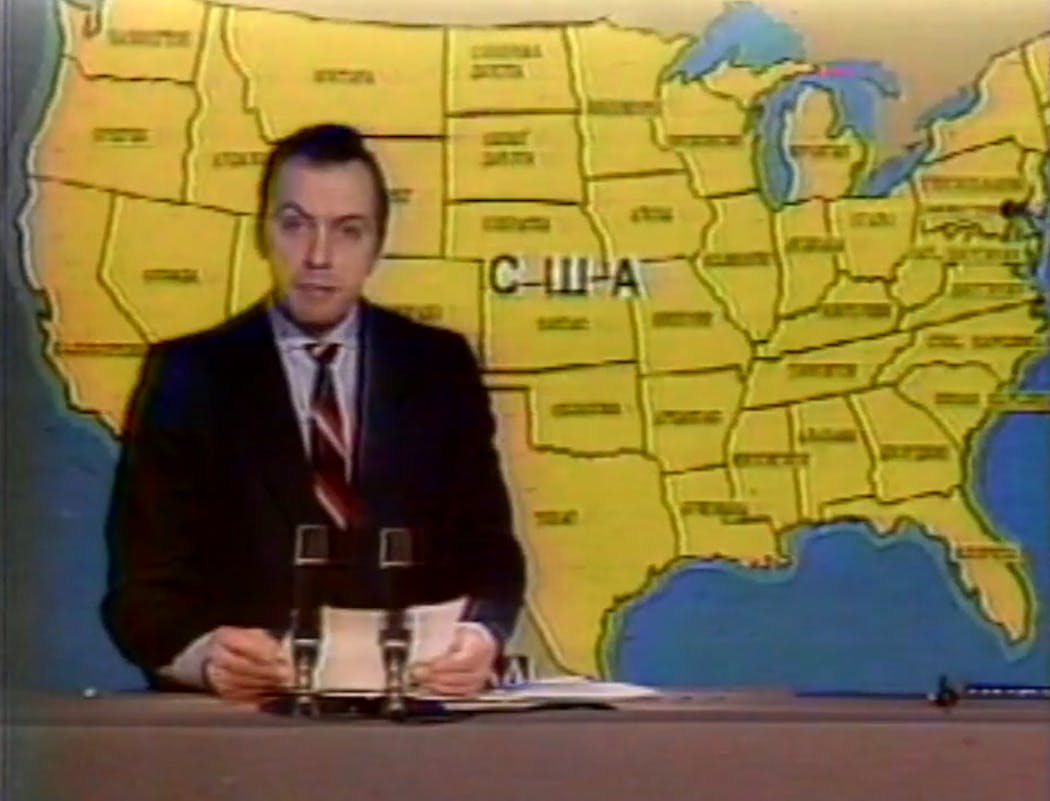

The show aired on Twin Cities Public Television (TPT) from 1985 to 1988. It was a mashup of clips from the Soviet news program "Vremya," presented along with commentary. And it was so novel at the time that it garnered a write-up in the New York Times.

Barry Cipra recently heard about the show from former TPT producer Bill Hanley. He felt it had new relevance today in light of the war in Ukraine and the criticism of journalism in Russia. Cipra turned to Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reader-powered reporting project, to learn more about the program.

"The topic struck me as interesting when I saw some clips of the show online," said Cipra, a friend of Hanley's. "I think it was a great idea at the time to offer Americans some insight into the Soviet view of things, and kind of amazing it was a Minnesota station that put it together."

"Channel 3 Moscow" is a tale of feeds swiped from satellites and a relic from a singular moment in history when Soviet media was evolving and Americans were curious about life behind the Iron Curtain as it began to fall.

How it started

"Channel 3 Moscow" started as a weekly segment on TPT's news series "Almanac." It came about as a solution to a problem: What could they put on "Almanac" in the summer, when news about politics and other topics slowed down?

One day, Hanley walked by an associate producer who was watching a clip of Soviet children singing the American protest song "We Shall Overcome."

The producer said there was "this priest in Omaha at Creighton University, who was regularly downloading Soviet television to use in his Russian language classes," Hanley said. "And I thought: 'Hey, this is a regular segment I could do with this show.'"

So Hanley flew to Omaha and asked the priest to send him the main Soviet news program "Vremya" (which means "time" in Russian) every week. Hanley said the priest used an early Apple computer to track a Soviet TV satellite and extract the TV feeds.

TPT was aware that viewers might consider "Channel 3 Moscow" to be spreading Soviet propaganda. But the feedback was so positive that soon it became a regular monthly show.

The channel collected excerpts of Soviet programs and aired translated clips with commentary by the hosts and a guest expert in the studio.

"Most of us have a lot of stereotypes about life in the Soviet Union," said the co-host Joe Summers in the first episode. "In our minds' eye, the pictures are uniformly gray. Life in Moscow is at best highly organized, at worst dull and depressing. Daily programming on Soviet television will confirm some of the stereotypes, but shatter others."

The expert in the studio was Nick Hayes, a former professor of Soviet history and culture from Hamline University. "The 'Channel 3 Moscow' experience was for me the golden peak of my career," he said in a recent interview.

The only time it was possible

The second half of the 1980s may have been the only time "Channel 3 Moscow" could have possibly existed.

Back then, the policies of glasnost and perestroika announced by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev meant the liberalization of the media and easing of foreign policy.

"It does seem like we were in this period between repressions of the old Soviet media and the new Russian repression of media," Hanley said. "Journalists working on television were legitimately struggling to be more and more open. They knew the opportunity they were being given and they were trying like crazy to do things."

Cipra, who sent the question to Curious Minnesota, remembers how shocked he was to see a performance by the Russian Army Choir singing "God Bless America" back in those days.

"I had grown up in the 1950s and '60s, during the fad for fallout shelters and other manifestations of the Cold War," Cipra said. "So this spoke volumes about the evolution of U.S.-Soviet relations."

Even though there were several stories critical of Soviet life in the "Vremya" program of that time — like one about a shortage of wallpaper — Soviet journalists also didn't hesitate to scold the Western world.

In one news item shown on "Channel 3 Moscow," for example, Soviet viewers were told about the U.S. Nazi Party and an American mother teaching her daughter to bake a cake with a swastika on it.

"Channel 3 Moscow" turned out to be so popular that PBS, the national public television network, asked TPT to produce a national episode. It aired in 1986 with Mark Russell as host.

A New York Times review said the program was "an uneven experiment, a bit more apprehensive than it need be. But the attempt to undertake what [TPT] describes as 'a modest effort toward international understanding' is valuable and, to say the least, timely."

But the reaction didn't just come from the American media.

As soon as the show was aired nationally, the State Committee of Television and Radio Broadcasting of the Soviet Union (Gosteleradio) sent PBS a cease-and-desist letter.

"The thing that made it work and made PBS legal was they [the Soviets] never encrypted it," Hanley said. "It was sent out naked. 'Cause they figured: Who's gonna be watching?"

Additionally, TPT concluded that no treaties barred them from airing Soviet intellectual property.

Events then took an unexpected turn.

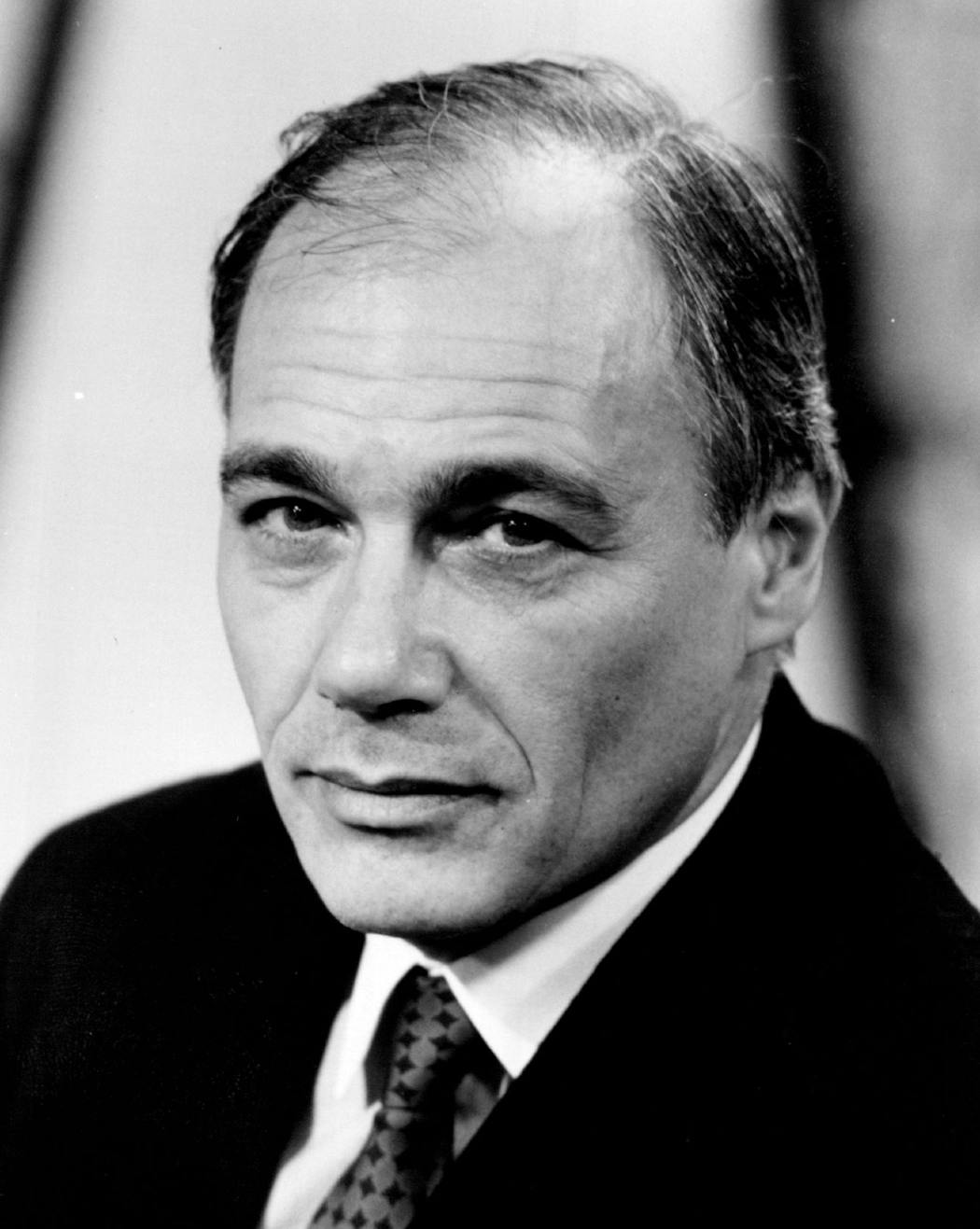

Hanley recalled that one day, one of the most famous Soviet journalists abroad, Vladimir Pozner, arrived unannounced at his office in St. Paul, accompanied by several Minnesotans sympathetic to the U.S.S.R. Pozner wanted to see the program.

"His bosses at Gosteleradio had told him that it was a horrible thing and they wanted him to investigate it," Hanley said. Once he saw the show, however, Pozner said it was professionally done and promised to arrange a meeting for Hanley and Hayes with Gosteleradio executives in Moscow.

The pair ultimately traveled to Moscow, where they met personally with the director of Gosteleradio, Valentin Lazutkin. Lazutkin told them that they could visit the U.S.S.R. any time and they would not be under surveillance. This resulted in a number of TPT documentaries produced on location in the U.S.S.R.

A new relevance

"Channel 3 Moscow" helped an American audience see Soviets not merely as symbols of evil, but as humans. The program is a reminder that understanding other cultures and seeing people as people first and foremost are the keys to better international dialogue.

Hayes said the "Channel 3 Moscow" broadcasts also offer a window into an important evolution in Soviet society.

"There was this people-to-people connection that came from many Russians … particularly in journalism and the media field," Hayes said. "That led the groundwork for criticism of the country itself, criticism of foreign policy."

Today, many Russian journalists agree that the late 1980s were one of the best periods in the history of journalism in the country. Just a few years before, federal TV channels would not air even the slightest criticism of the authorities. By the early 1990s, Soviet and then Russian journalism had gone from absolute censorship to unprecedented freedom.

This suggests that the same is possible today.

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Was Minnesota home to nuclear missiles during the Cold War?

Why does Minnesota test tornado sirens on the first Wednesday of the month??

Why did Finnish immigrants come to Minnesota? (And no, they're not Scandinavian)

Why didn't Minneapolis gobble up its suburbs?

Why do Minnesotans have accents?

Why do so many Fortune 500 companies call Minnesota home?