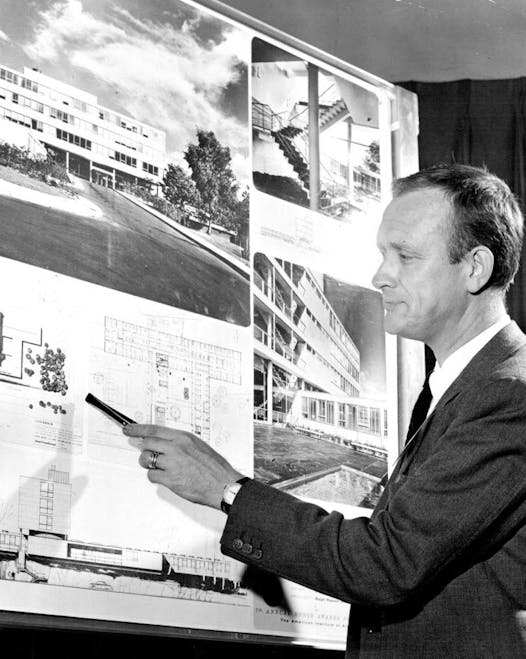

Ralph Rapson is the Prince of Minnesota architecture — with a capital "P." Just as the Purple One spread the sound of Minneapolis funk, Rapson spread Minnesota modernism as head of the University of Minnesota's architecture school for 30 years — and a practitioner based here for more than 50.

His own creations, most notably the original Guthrie Theater, are hailed as fresh yet fully formed examples of the iconoclastic spirit that drove design in the second half of the 20th century.

But for all he did during his 93 years, which ended in 2008, is Rapson's influence still vital today in the built environment of the Twin Cities?

The answer is a resounding yes, according to architects and scholars who will gather next weekend to celebrate Rapson's legacy through the scholarship program he inspired.

"His whole idea of the architect as master designer, from the furniture to the building, is alive and well," said Nancy Blankfard, a principal with the Minneapolis firm HGA who won a Rapson Traveling Fellowship in 1997.

For 25 years, young architects have competed to become Rapson fellows, with winners getting a stipend to travel and study. Rapson believed travel and exposure to other built environments were vital to an architect's professional development.

Matt Kreilich studied at the U of M in the immediate post-Rapson years and won a Rapson fellowship in 2004. Now a partner in Snow Kreilich Architects of Minneapolis, he said Rapson's most powerful legacy may be the way he put people at the center of his projects.

"I think that approach to architecture is really important," Kreilich said. Rapson's own project drawings, he said, "were animated and filled with life and people. That quality of how people engaged in spaces within and around buildings really came to life in his work."

Kreilich said he drew on that inspiration in one of his own recent designs, the Brunsfield North Loop apartment building in Minneapolis, which opened in 2013. The project features outdoor spaces "that blur the public and the private realm," Kreilich said. The same can be said for the newly opened CHS Field, home of the St. Paul Saints, designed by Kreilich's partner, Julie Snow.

"Rapson's DNA can be seen in the work of local architects who are designing buildings for people first and foremost," Kreilich added. "It's the quality of light, and the material, and the views, and the richness of the experience."

Though Rapson is usually identified as a modernist, it may be too easy to pigeonhole him with that label, said Jane King Hession, an Edina architectural historian and co-author of "Ralph Rapson: Sixty Years of Modern Design."

"It's hard to wrap modernism into a nice, neat package," Hession said. "Ralph was a modern architect in that he wasn't looking to repeat what had been done before. He was looking at how people lived, and how architecture could best address those questions."

Without a doubt, the quintessential Rapson building is the original Guthrie Theater, Hession said.

"I have always said that the Guthrie is the building that was most like Ralph himself," she said. "It was a very serious, well-considered building. But Ralph also had an element of whimsy and fun and welcomeness."

Here's an occasion when experts and the public are in easy agreement. For generations of Minnesotans, including this writer, a trip to the old Guthrie — especially the first trip — was a deeply memorable experience.

Less known to the general public are Rapson's groundbreaking designs for nine American embassies overseas in the aftermath of World War II. Those projects, Hession said, helped create a new design language for important public buildings.

"They demonstrated that modernism was suited to embassies and diplomatic enclaves," she said. "In the same way, when he came here and designed the Guthrie Theater, he demonstrated that modernism could be part of our landscape and was an appropriate style for the period and the place, Minnesota."

Stillwater architect Brian Larson won the first Rapson fellowship in 1989. Rapson himself came to prominence as a young architect through success in design competitions, Larson noted, so the competition for a Rapson fellowship is in keeping with the spirit of its namesake.

"At that point in his career, architecture was transitioning from a classical Beaux-Arts style to modernism," Larson said. "And these competitions were a chance for modernist architects to stretch their wings and show what could be done."

In that vein, the design briefs for Rapson fellowship competitions have always been ambitious. In the competition's first year, Larson's task was nothing less than designing an iconic monument for the state of Minnesota. His winning submission was a 600-foot tower in downtown Minneapolis that would change with the seasons. In the temperate months, it would be covered in flowering vines. In the winter, it would become a tower of ice through a trickler watering system.

"Ralph was really thinking of how architecture and modern life could come together," Hession said. "If you look at his houses, they don't necessarily look like his university buildings, and the university buildings don't look like his theaters.

"One has to wonder: If Ralph was with us today, would his architecture take on a different character?"

John Reinan • 612-673-7402

Sour Patch Kids Oreos? Peeps Pepsi? What's behind the weird flavors popping up on store shelves

The unstoppable duo of Emma Stone and Yorgos Lanthimos