Marv Wolfenson, who with his lifelong business partner brought the NBA back to Minnesota decades after the champion Lakers left for Los Angeles, died early Saturday surrounded by his wife, children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren in La Jolla, Calif. He was 87.

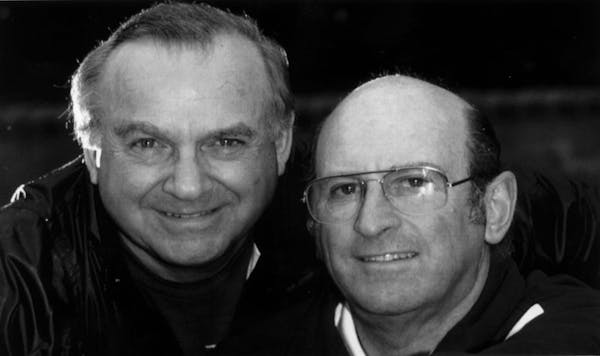

Grade-school friends from their childhoods in north Minneapolis, Wolfenson and Harvey Ratner were partners in real estate and health clubs, but they became famous on the Twin Cities sporting landscape as "Harv and Marv" when they pursued and purchased an NBA expansion franchise in 1987 and then privately financed the construction of Target Center, which opened as the home for their fledgling Timberwolves three years later.

They partnered for 54 years, a study of opposites who shared a simple room — with no receptionist and an open door — at one of their entrepreneurial Northwest Athletic health clubs for a good part of that time.

Ratner was the calm and introspective impeccable dresser who was a bench warmer when the two attended high school together. Wolfenson was the boisterous, opinionated star athlete who seldom was seen during his professional years in anything but an open-collared sport shirt, although he did rock the red leather pants well into his 60s.

"In some ways, they were absolutely the opposite of each other, and in some ways they weren't," Bob Stein, Wolfenson's former son-in-law who ran the Wolves for the seven years Wolfenson and Ratner owned the franchise, said when reached by phone. "They complemented each other. They were really good partners."

Ratner died in 2006.

In poor health for parts of the past decade, Wolfenson until very recently put on every morning the NBA logo baseball cap and Wolves staff credential the team sent him annually since he and Ratner sold the team.

"Never saw him without it," said granddaughter Lauren Sundick, who called his passing in Saturday's early hours surrounded by wife Elayne and family "heartbreaking but extremely peaceful."

Wolfenson had talked his more conservative partner into owning a pro sports team. Early in their business career, they helped try to keep the Minneapolis Lakers from moving away to California in 1960. In the early 1980s, they pursued the Twins before Carl Pohlad bought them and a few years later they came within hours of striking a deal to buy the NBA's Utah Jazz.

Eventually, they paid $32.5 million for an expansion franchise, saying they wanted to return the NBA to Minnesota and give something back to the community in which they were born, raised and called home all their lives.

In doing so, they brought back a man with Minnesota connections — controversial former Gophers coach Bill Musselman — to be their first coach. Musselman in turn brought in a young college assistant coach named Tom Thibodeau. All these years later, Thibodeau now is the successful head coach of the Chicago Bulls.

"To me, Marv had great wisdom," Thibodeau said Saturday. "He didn't overreact to things. He didn't underreact to things. I know how important it was for Harv and Marv to get that team. They took a big chance on bringing Bill back, and I know how fond Bill was of Harv and Marv and I certainly appreciated what they did for him and did for me.

"I was very fortunate. I was a young guy without experience. I didn't even know which way was up. Marv was great to me, phenomenal. I learned a ton from him and appreciated all he did for me."

Wolfenson and Ratner themselves financed Target Center, a $65 million project that turned into a $94 million completed arena. The costs overextended them financially and forced the pair to sell the team. In 1994, they struck a deal with a New Orleans group that planned to move the Wolves after only five seasons of existence. NBA Commissioner David Stern stepped in and brokered a deal that sold the team for $88 million to Mankato businessman Glen Taylor, who kept the franchise in Minnesota. The city of Minneapolis bought Target Center the next year.

Employees from the Wolves' formative seasons remembered Wolfenson fondly Saturday on Facebook pages and in conversations as a mentor and storyteller who didn't have the patience for but the very briefest of phone calls and yet would entertain for hours over dinner or after a movie.

He often attended practices and traveled with the team, bringing along childhood friends with whom he would kibbitz like they were all 12 years old again. He would hop a cab early to games with the team's young equipment manager, Clayton Wilson, and take him to movies during off days on the road.

It was an unexpected friendship, a kid not long out of college making $12,000 a year washing smelly uniforms and a multimillionaire NBA owner.

"He would buy the tickets and I'd buy the popcorn," said Wilson, a former Twins clubhouse attendant whom Kirby Puckett also befriended. "I've been blessed to have people in my life that I had instant connections with that last for some reason. Marvin and I were like that for some reason. We just clicked."

Wolfenson didn't sleep well at nights, so he napped days. One evening, the Charlotte scoreboard video caught him snoozing during a timeout contest that chose the fan of the game, an honor he won overwhelmingly by fan applause even though the audience didn't know he was the opponent's owner.

He woke up long enough — and was thrilled — to receive a prize pack that included a Hornets bag, T-shirt and cap.

"It's the simple things, isn't it?" said Wolves President Chris Wright, whom Wolfenson and Ratner hired the year the team moved into Target Center. "People can make a tremendous amount of money, but with Marv it was always the simple, little things. It really was."

The funeral will be held at noon Thursday at Temple Israel in Minneapolis.

Gordon, Jokic lead the Nuggets to the brink of a sweep with a 112-105 win over the Lakers in Game 3

Twins bring momentum into next series despite Angels Stadium struggles

Five home runs, including two by Julien, power Twins past White Sox