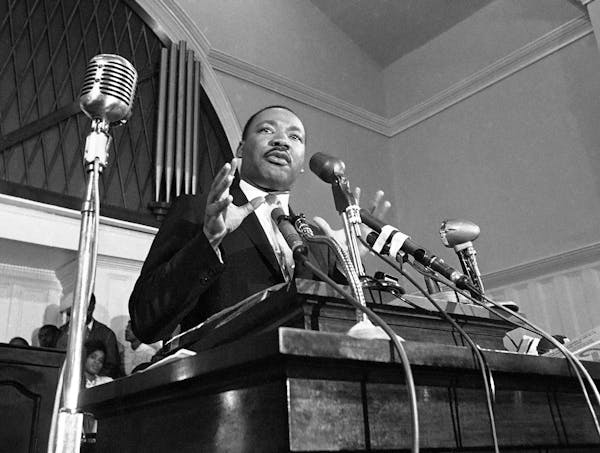

Like the rest of the nation, Twin Cities residents were stunned on April 4, 1968, to learn that Martin Luther King Jr., the nation's pre-eminent civil rights leader, had been assassinated in Memphis.

Black residents in the community felt a combination of sorrow, frustration and anger.

"I could hardly believe a man who had been preaching love and patience could be assassinated," recalled Josie Johnson, who was acting president of the Minneapolis Urban League at the time.

"We were traumatized," Spike Moss, 72, a longtime local black activist, said Tuesday. "Women and children were crying and wailing. I didn't think I would survive that day."

Some 300 people jammed the Sabathani Baptist Church in south Minneapolis that night. Five hundred people, many from the University of Minnesota, marched on City Hall the next day, and 5,000 turned out for events on Sunday, including 3,000 who marched through the streets of Minneapolis.

"The city was in an uproar," recalled Ron Edwards, who was vice chair of the Minneapolis Civil Rights Commission. "We were being called on to try to keep the lid on the city. It was the end of the world as far as people were concerned."

Gary Hines, now the music director for the Grammy-winning Sounds of Blackness, was a 15-year-old student at Minneapolis Central High School, where he was leader of a group called DECOY, Determined Ebony Council of Youth.

"There was anger and frustration," he said. "The last time I had witnessed and felt that level of outrage was when four girls were killed in Birmingham," the infamous bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church by white supremacists in 1963.

Edwards, Moss and Hines all recalled fires being set in the city as the anger spread. Moss remembers Molotov cocktails being thrown. He remembered when a local black man, Clarence Underwood, 27, declared: "They just killed our King, they just killed our leader." Underwood then went out and shot and killed the first white man he saw, John Frank Murray, 25, on the North Side.

There were reports of whites firing into the cars of black people.

Hines said he joined black patrols, which paired a young person with an older person, who went through black neighborhoods trying to calm distressed youth.

One night, he drove with Minneapolis Lakers basketball player Bob Williams. Another night he drove with Harry Davis, one of the most prominent black figures in Minneapolis, who was later the DFL's unsuccessful candidate for mayor.

"We can't swallow the bitter pill of hatred with revenge," Davis declared at a news conference in Mayor Arthur Naftalin's office.

City leaders were anxious, recalled Edwards, who attended a Civil Rights Commission meeting at 1:30 a.m. at City Hall only hours after the shooting.

"Things were so tenuous, General Mills chartered a DC-8 and flew a significant number of African-Americans to Atlanta, Georgia, to attend King's funeral," said Edwards. He said he joined Josie Johnson, civil rights activist Nellie Stone Johnson and Curtis Chivers, of the Minneapolis Spokesman newspaper, on the trip.

Fifty years later, some of the activists of that era express despair that the goals of equality for which King gave his life have not been achieved.

"I feel America is going backward," Moss said. "Its racism is more emboldened than it was in the 1950s."

Bill English is consulting project director of the Northside Job Creation Team in Minneapolis. Fifty years ago, he was director of the Sabathani Youth Center, and addressed the gathering at the church, acknowledging their anger, but urging people to remain nonviolent.

Today, he says, things aren't much better. English, 81, cited local racial disparities and the shooting deaths of Trayvon Martin; Philando Castile; and Stephon Clark in Sacramento; the prosecution of Mohamed Noor, the Somali police officer, for killing Justine Ruszczyk Damond, when white officers were not prosecuted in the local shooting of Jamar Clark.

"I am tired of commemorating the [King] assassination because we are almost as bad off now as we were then," he said.

Staff researcher John Wareham contributed to this report.

Randy Furst • 612-673-4224

Icehouse owner hopes to avoid evection as music scene rallies around Eat Street venue

Edina man admits to fatally shooting a man in Minneapolis during dispute over money

After an ATF ruling, the bottom falls out for a St. Cloud firearms manufacturer

Duluth mayor pledges population growth in the long-stalled city