Was the Minneapolis Park Board created to benefit wealthy land owners?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

Compared with other American cities, Minneapolis has vested an unusual amount of political power in its parks.

The city's award-winning park system is overseen by a semiautonomous government, the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board. The agency has elected commissioners, its own police force and an annual budget pushing $140 million. And since its inception in the 1880s, it has crusaded to convert the city's private land into public parks.

Reader Carol Becker, a former member of the city's Board of Estimate and Taxation, advocates raising taxes to benefit parks. She believes recreation is one of the best ways to empower the city's young residents.

But she is also skeptical about stories painting the Park Board's founding fathers as civic heroes who used their wealth to promote public places out of concern for women, children and the poor.

"You can go, 'Wow, it was out of the goodness of their heart that they wanted a thriving city,'" she said. "No, no, they made bank. I just think that's part of the story."

Becker vaguely recalls reading about "fistfights in the streets, ballot stuffing and developers wanting parks to make money" while perusing old newspapers some decades back. So she sought more information about the board's creation from Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reader-powered reporting project.

A call for parks

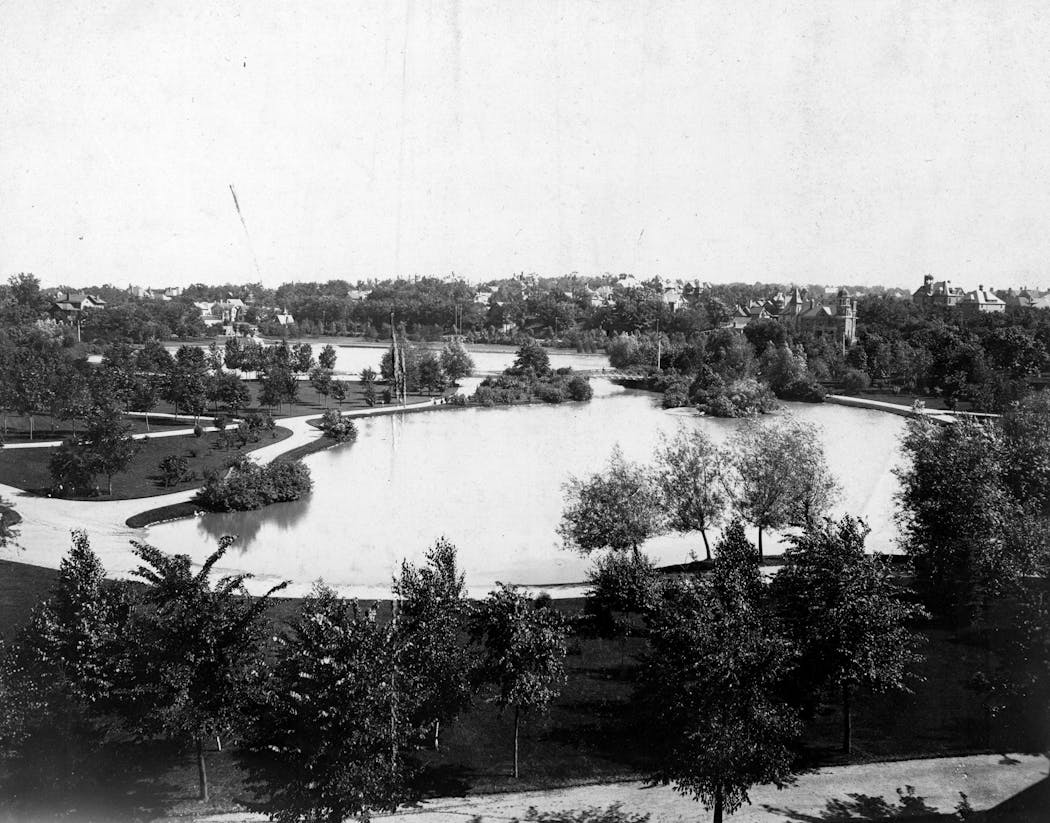

Recreation was not a priority for the developing frontier town of Minneapolis in the mid-19th century. The city councils of the era were busy building bridges and hospitals. Despite a brewing clamor for public parks, city leaders repeatedly rejected proposals to create them. Without green space, many residents picnicked in Lakewood Cemetery.

"Those who are opposing the park system ought to carry a banner inscribed, 'War upon mothers and babies — no fresh air for the women and little ones,'" quipped the Daily Minnesota Tribune, which used biting sarcasm to scold anti-park aldermen.

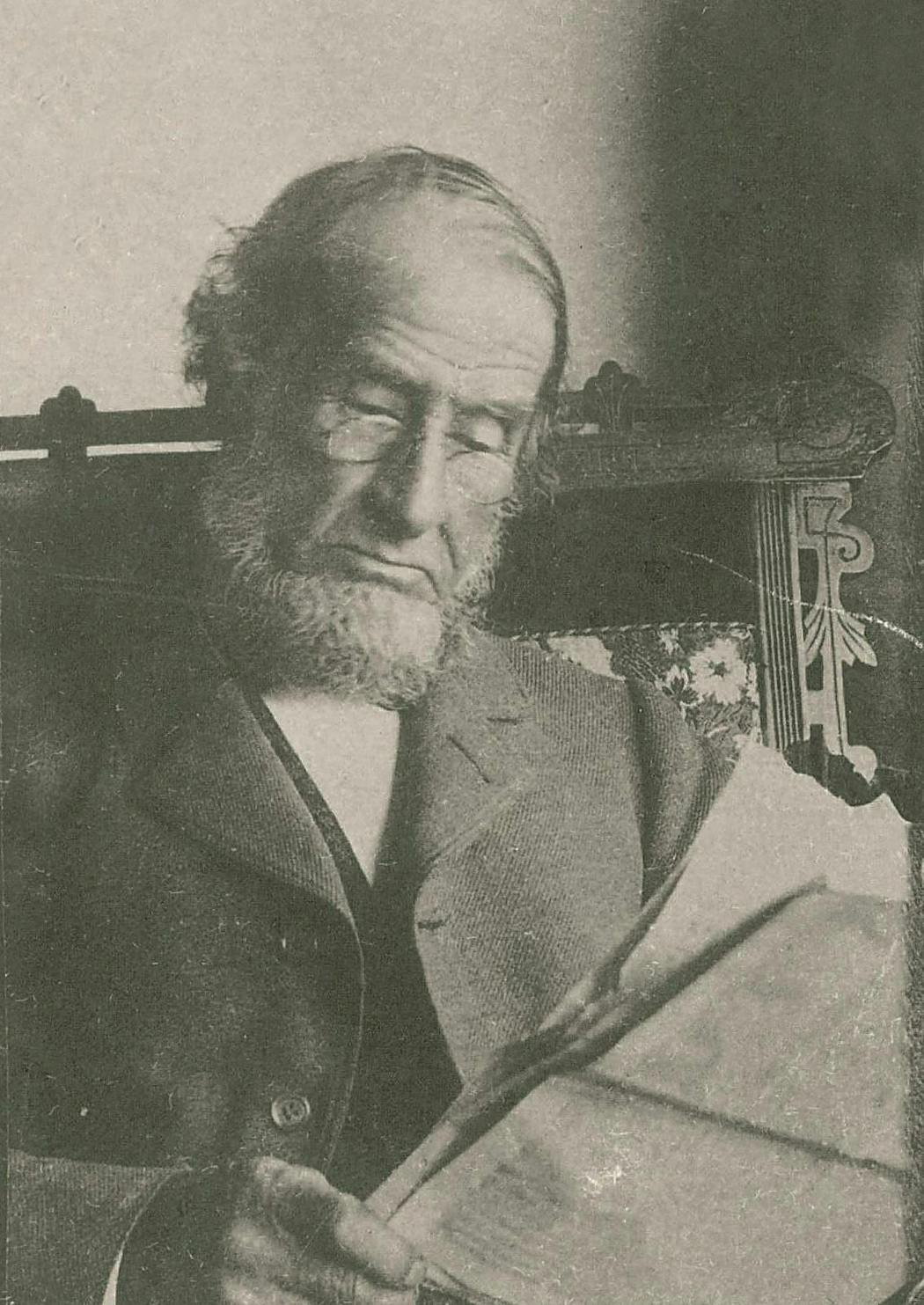

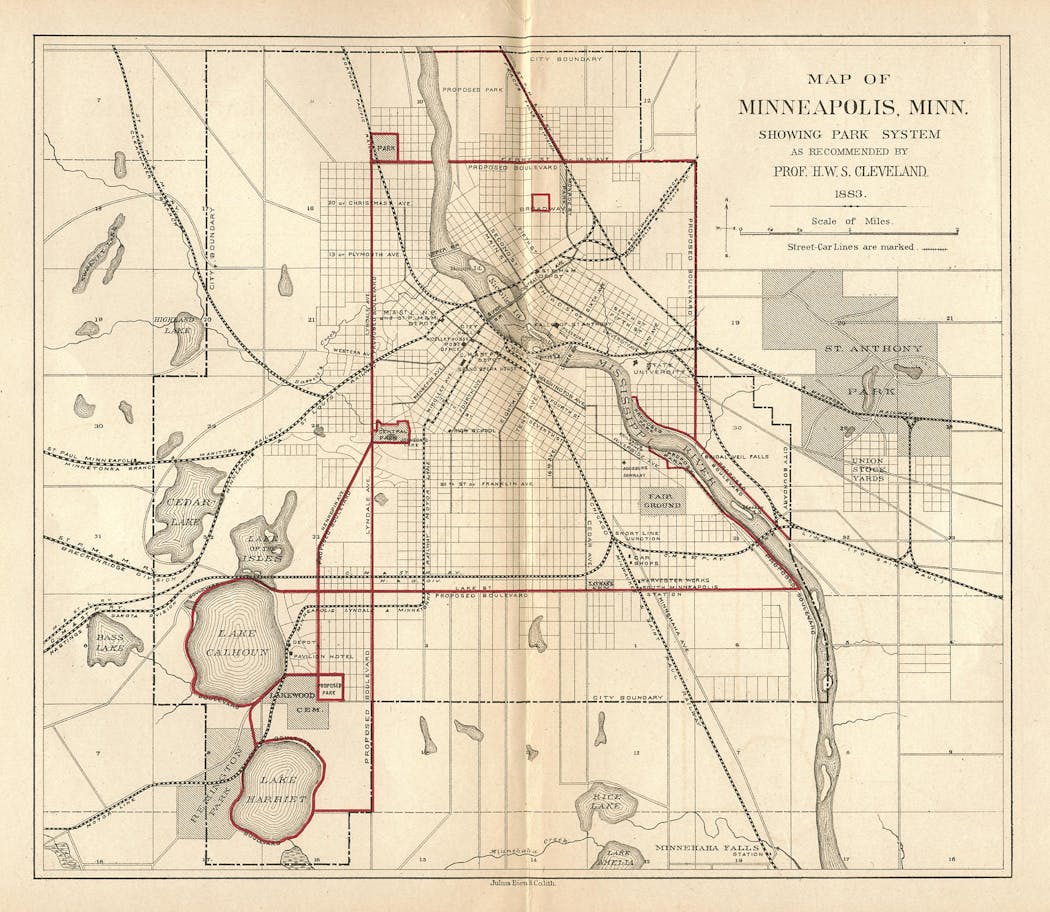

Visionary landscape architect Horace Cleveland helped win support for the cause during an 1872 speech at downtown's Pence Opera House, according to David C. Smith's lyrical history of the Park Board, "City of Parks." Cleveland urged city leaders to preserve the "mystery and beauty" of the city's natural resources.

He regaled city leaders on the wonders of New York's brand-new Central Park — as well as the increased value of properties surrounding it — and urged them to purchase still affordable land in Minneapolis for a sweeping, planned park system.

The message found fertile ground in the imaginations of the city's elite. Among them was Charles Loring, the businessman and civic booster who became known as the "Father of Minneapolis Parks." Smith speculated that Cleveland and Loring bonded over personal tragedies that made them both caretakers of young children in old age — and subsequent champions of playgrounds.

"I think the motives of [the early park advocates] were pretty positive, pretty noble," Smith said. "I think they really did believe that a park system would benefit everybody."

Smith recalled that Loring once argued, for example, that wealthy people like him had carriages to get fresh air out in the country, while it was the people without carriages who needed parks.

Progress or power grab?

Political winds suddenly changed in favor of park advocates in 1883.

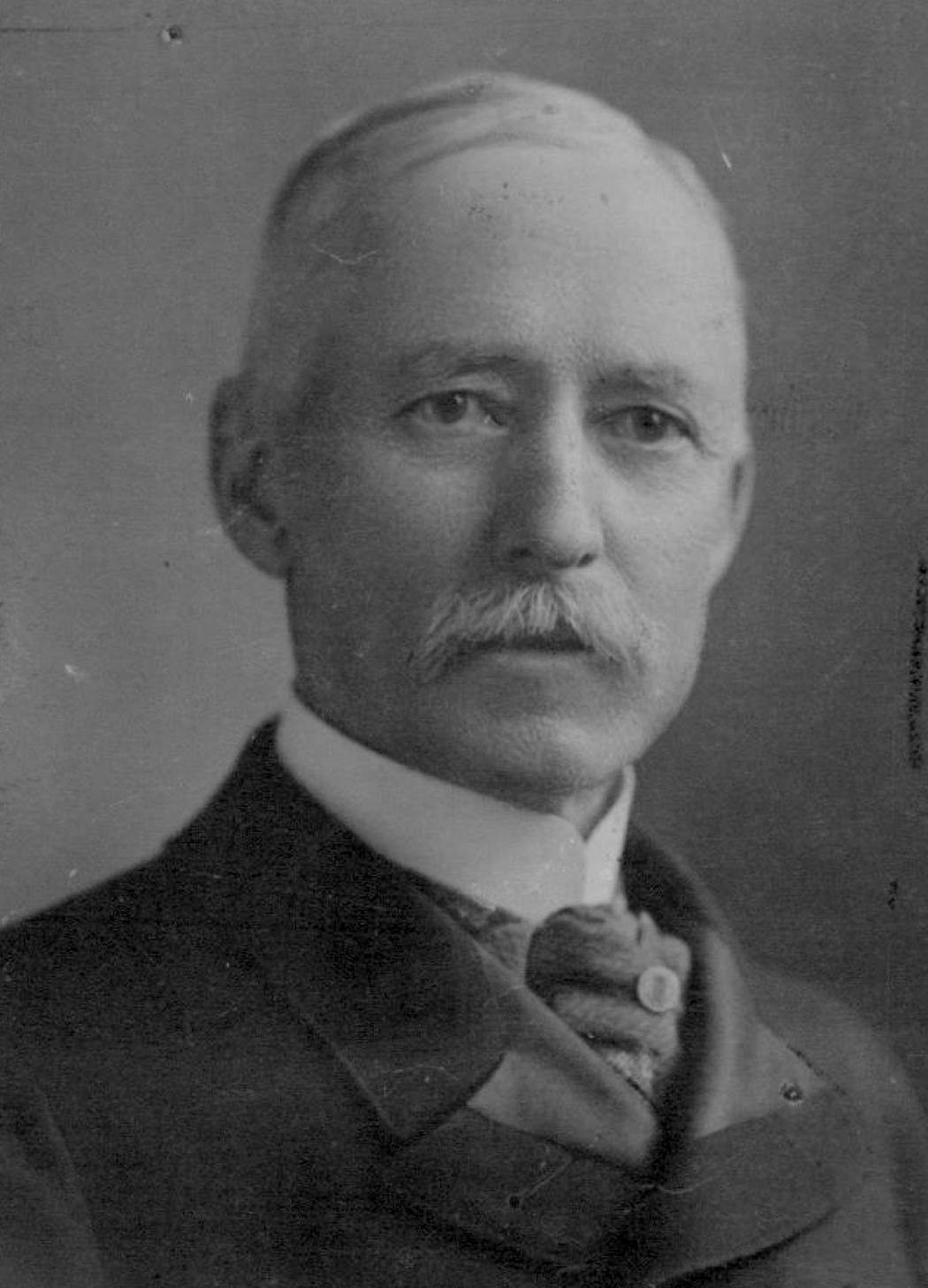

Loring's business partner, Republican legislator Loren Fletcher, was named speaker of the Minnesota House. A group of influential Minneapolis businessmen, meanwhile, jump-started the dormant Board of Trade — an early Chamber of Commerce. With Loring's friends in key positions, they pushed through a bill to let Minneapolis voters decide whether to circumvent the City Council and form a governing body for creating and maintaining parks.

Some found the details alarming. The first Park Board commissioners would be appointed (only later would they be elected) to buy huge tracts of land with the power of taxation and eminent domain.

Fissures appeared along political lines. The partisan press exchanged fire.

The Republican-leaning Minnesota Tribune argued parks would create jobs. The paper admonished that "the citizen who votes against the park measure votes to turn back the hands on the dial of Minneapolis progress at least a quarter of a century."

The Democratic-leaning St. Paul Globe was suspicious, pointing out that the proposed park commissioners were all landed capitalists. "There is probably not a man in Minneapolis who is opposed to the establishment of a park system, but a majority is opposed to the cunning trickery of the park bill," the paper wrote.

The Knights of Labor, an early union organization, also came out against the initiative. "The door is left open to rob the working classes of their homes and make driveways for the rich at the expense of the poor," the group wrote.

Smith believes that the class divide has been exaggerated over the years. He points out that a leading Democrat of the day, E.M. Wilson, sent the Tribune an emphatic defense of the Park Board.

"The bill presented for our consideration is by no means perfect, but its defects are small compared with the public misfortune of its defeat," Wilson wrote. "We need most small square and parks close within the city. These can be reached easily on foot and on street cars. The opportunity to have these is rapidly passing."

On the day of the vote, April 3, 1883, an early edition of the Minneapolis Journal lamented that the Park Board was doomed because a cloudy morning and muddy streets kept voters home. By the next morning, however, the paper effusively declared victory for the park bill: "[Supporters] rallied in force to the polls and brought a magnificent victory out of the jaws of defeat."

Democratic Mayor Albert "Doc" Ames, who opposed the Park Board, was not impressed. He told the Globe that Republican park advocates, including newspaper boss William King, schemed with the influential liquor dealers to drive up votes for parks in return for low licensing fees on saloons.

King denied the allegations. The Tribune called Ames an imbecile. Grumblings of fraud did not hinder the creation of the Park Board, however.

As for the fistfights, Smith said he has not encountered election violence in any of his research. A search of this newspaper's archive also came up empty.

Who profited?

Did developers get rich from the creation of beautiful parks? Undoubtedly.

King donated the north shore of Lake Harriet and part of his Lyndale Farm for the creation of Lyndale Park in 1890, according to the Minneapolis Park Board's historical records. But his charity came with conditions: King wanted the Park Board to develop the park and build a road through it within five years. He asked that the rest of his land in the area be temporarily exempted from assessments.

"The donation of land for parks was motivated at times in those days by the likely appreciation of adjoining land when a park was created. Park-front property was highly desirable," according to the Park Board's history of Lyndale Park, written by Smith. "This proved true in the case of Lyndale Park even before King's donation was accepted. Newspapers reported that lots near the proposed park nearly tripled in value when the donation was first announced."

As Minneapolis grew into the 20th century, park planners and real estate developers maintained a symbiotic relationship. Parks Superintendent Theodore Wirth made drastic changes to the natural landscape — including dredging shallow wetlands to make deep lakes — to create impactful parks as well as the neighborhoods of south Minneapolis.

"The entire area comprising Nokomis and Hiawatha Parks two decades ago was useless land which impeded growth of the city in that large south section," Wirth said in 1934. "Once the delayed growth of the city in that direction was stimulated; property values increased."

The people benefited as well. Minneapolis parks are consistently ranked among the best in the country. The Park Board spends $317 per resident annually, ensuring 98% of residents live within a 10-minute walk of a park. Almost all of the city's waterfront has been made public property.

An entity like the Minneapolis Park Board is rare among major cities, Smith reflected.

"In almost all cases, it's very unusual for a political body to give up power," he said. "And in Minneapolis that wouldn't have happened either, except for the fact that all the stars aligned to allow the Legislature to take that power."

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

How did Nicollet Island become parkland with private housing on it?

Is it true that Minneapolis has a park every six blocks?

Why is the BWCA a wilderness and not a national park?

Why did Minneapolis' famous flour boom go bust?

Why is Uptown south of downtown in Minneapolis?

Why is 'southeast' Minneapolis actually northeast of downtown?