There's a certain type of grown-up who waxes nostalgic about the summer camp. They'll tell you it was magical. That it somehow slowed time. That they discovered parts of themselves they didn't know existed.

And, for a smaller subset, it is no exaggeration when they say summer camp radically changed their lives.

"Camp is this magical space where you get to be the authentic version of yourself," says Sara Lemke, director of development and communications for Camp Fire Minnesota in Excelsior, Minn. "You're so detached from the world. You don't have technology. Maybe at some point, you don't have your peers. You're plopped into an environment where you are experiencing new things together."

Out under the pine trees or on a glistening lake, relationships can deepen.

Lemke, 33, would know. While in middle school, she attended a summer camp where she fell hard for a blue-eyed boy she spotted at mealtime. Years later, she married him. They now have a 3-year-old son (who, by the way, will definitely be going to summer camp).

In July, my soon-to-be sixth-grader will pack up his rucksack for his first week away from home to attend a summer camp in northern Minnesota. I worry he'll be homesick, even though it is probably I who will miss him more. I hope he experiences a taste of freedom and independence and gains permission to explore nature as much as his sense of self.

Will his summer camp experience be as pivotal as the Minnesotans I found? Hard to say. Either way, it was nothing short of enchanting to hear how their lives were forever transformed during their magical summers in the woods. Here are their stories.

The couple

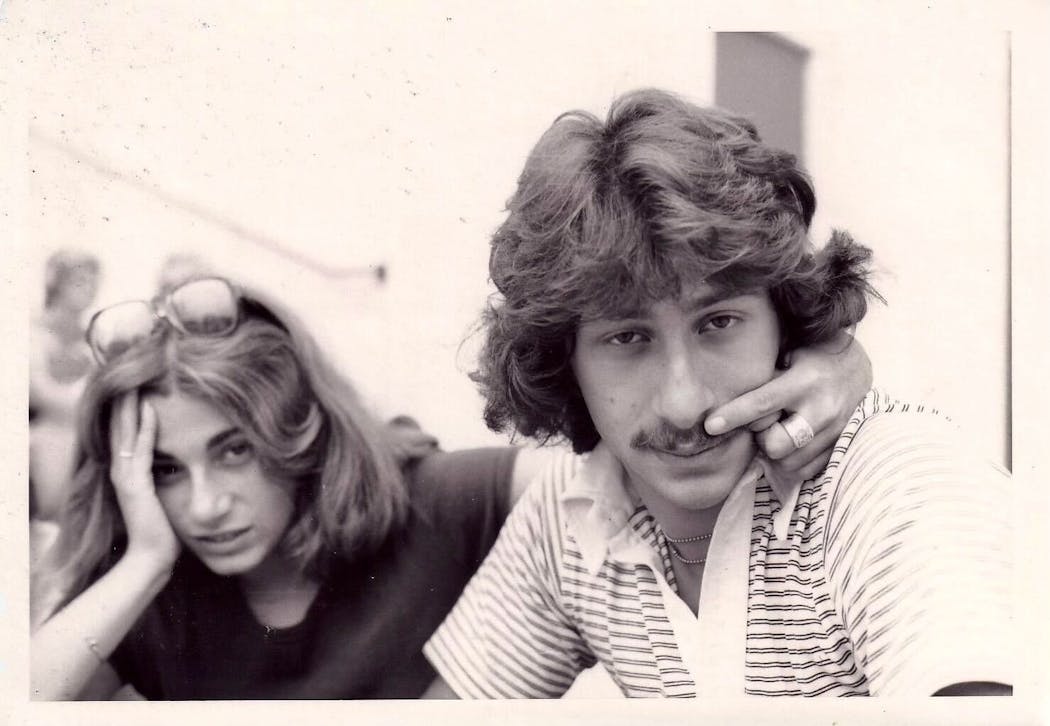

Carolyn Bloom remembers zeroing in on her future husband, Stuart, in the summer of 1976, while they both worked as counselors at Herzl Camp in Webster, Wis. He sported a bandana around his neck and a purple Chevy trucker hat.

"Stuart had a big personality back then," Carolyn, 66, recalls. "I of course noticed him. He was cute."

"I thought she was hot," says the 65-year-old Stuart, his eyes growing wider. (He added later that he was also attracted to her intellect.)

The two had just graduated from neighboring suburban high schools — Carolyn from St. Louis Park, and Stuart from Golden Valley — and knew of each other from local Jewish circles. They had even attended Herzl together as 13-year-old campers. But until that fateful summer as young adults, they hadn't deeply connected.

Their time as camp counselors afforded them the chance to have soulful conversations, far removed from school or parties back home.

On July 4, 1976, Stuart was in a communal building at camp while on his "shmira" shift, or guard duty, making sure the campers were safe at night. Carolyn paid him a visit. The two worked together on a bicentennial Star Tribune crossword puzzle that Stuart's mom had sent him. When they walked back to their cabins, it was impossible to ignore their attraction.

Carolyn and Stuart had seen Fourth of July fireworks from a field earlier in the evening, but now there were even more.

"It was a good night kiss that was more than a peck on the cheek," Carolyn remembers.

In retrospect, Stuart says, he knew after that summer that Carolyn would one day be his life partner. They later attended colleges on the East Coast, settled in New York, and managed a career shift that transitioned Stuart from a singing comedian to an oncologist and now professor, a job that has him shaping future doctors at the University of Minnesota. The couple, who live in Hopkins, reared three children and have two grandchildren.

Stuart says he still flexes the skills that he honed at summer camp.

"The same things that make you an extraordinary counselor make you a really good oncologist," he says. "You have to have a certain calm in the setting of somebody else's distress — it's the same with cancer and the kids who are homesick. And you have to be able to manage diarrhea."

Carolyn laughs. She says that summer at Herzl deepened her sense of "ruach," the Hebrew word for spirit, and understanding her obligations to the community. "We were encouraged to be independent, but also to have responsibility," she says, adding that those values served as a springboard into the rest of their lives.

"It was a magical time for us," she adds.

Stuart agrees. "And that feeling has never left."

The teacher

Even as a 13-year-old, Lalo Edmondson knew he wanted to be a teacher one day. But there was one problem: He was excruciatingly shy.

The middle-schooler was nervous leading up to his first experience at Camp Fire Minnesota. But when he set foot on the wooded shores of Lake Minnewashta, not far from his Minnetonka home, the community there welcomed him. It felt like a secluded and otherworldly bubble, reminding Edmondson of a scene from a Percy Jackson novel.

Edmondson was paired with a 5-year-old "buddy," who shared his first name, Eduardo. ("Lalo" is a common nickname for Eduardo.)

"This guy is literally like my mini version," says Edmondson. "I had to be more outgoing. I had to be a good leader and a good role model for my little buddy."

Edmondson discovered he had a knack for drawing kids out of their shell. Later, as a camp counselor, he strived to make them feel safe and comfortable while pushing them to try new experiences, whether it was kayaking or rock climbing. It wasn't tough to imagine their fears while stepping into a tippy canoe for the first time because he was once that kid, too.

He also knew innately what it was like to be an outsider; Edmondson was born in Mexico and moved to the U.S. when he was 8. Raised by a single mom who wanted to pass on her love of the outdoors, Edmondson says he wouldn't have had the chance to attend summer camp without the scholarship he received from Camp Fire Minnesota. Nearly half of its participants receive financial help.

"If it wasn't for that summer, I don't know where I'd be in life," says Edmondson, 25. "It's helped me to become who I am."

Edmondson didn't have the best grades growing up. But his summers at Camp Fire helped him see his path as a teacher. He found the motivation to go to college and thrived there. Now an ESL teacher at Burnsville High School, he exudes camp vibes in the classroom. Yes, he will sing a full-throated version of "Pizza Man," split the class into Team 1 and Team 2, and do the wave.

With his students who are fresh from another country, Edmondson says he strives to create a place much like the camp community that enveloped him: a bubble where they can discover their potential and be who they are.

"Every kid who comes to my school who is an outsider because of language or socioeconomics, it's like, 'Buddy, I understand you 100 percent,' " he says.

The BFFs

Carrie Bush kissed her first boy at summer camp. She doesn't recall his name. But she does remember befriending Abbey Bryduck.

In that summer of 1995 at YMCA Camp Icaghowan in Amery, Wis., the two camp counselors enjoyed deep conversations while lazing on the dock, admiring the shimmering stars at night. They were able to shed their high school personas and discover their true selves. Away from parents and the trappings of high school life, "there's a certain level of vulnerability that happens," Bush says.

Bryduck, 46, agrees. "When you're in school, it's about being cool: Who's cool? Am I cool? Is this cool?" she says. "In camp, it's not about being cool. It's about having fun, being very silly and including everybody. Carrie is especially good at being silly."

The giggles and the camp songs and the goofy skits helped them bond. But so was their sense of social responsibility. Everyone had a role to play, whether it was collecting sticks or pitching a tent. Their summers together built the beginnings of a friendship that has continued for nearly three decades.

"With that strong foundation, a relationship can grow and grow and grow," Bush, 50, said of Bryduck. "She's one of my first calls for anything big that's happened in my life. We drop everything and anything for each other."

Bush was Bryduck's maid of honor when she got married in 2009. Bush is also the godmother of Bryduck's 10-year-old son, Sidney.

"Somebody who knows you for that long, especially your formative years — she knows the context of me," Bryduck said.

When they think of how long their friendship has endured, she says, it's like a major investment they each made in another human.

"The reward is, you get someone like a sister," Bryduck says. "The intensity of a camp experience can set that off."

The environmentalist

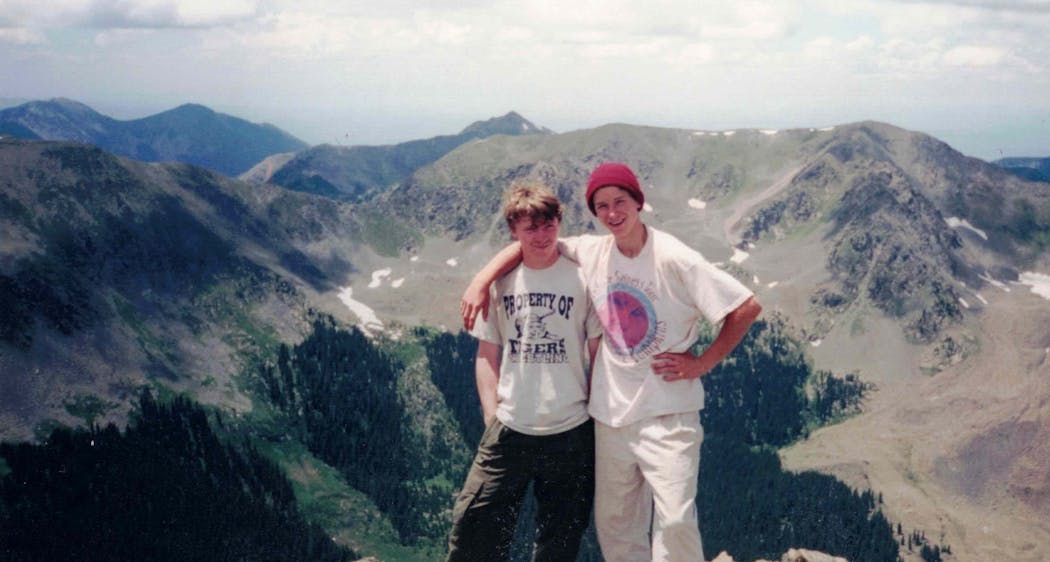

Peter LaFontaine always loved being outdoors as a kid, but his first intense foray into nature — and his first long stint away from home — came when he was 14 and embarked on a wilderness inquiry program based out of western New Mexico.

For about a month, he and his fellow trekkers traveled the Four Corners states, everything from the high mountains to massive sand dunes. He backpacked, canoed, car-camped and immersed himself in Navajo and Hopi reservation communities. For this white middle-class kid plucked from his New Hampshire roots, the exploration couldn't have been further from home.

"The distance was geographical, but also cultural and in mindset," says the 41-year-old LaFontaine, who now lives in Minneapolis. "I was so far outside my experience that it could not have been more alien than if it was on Mars. ... There are deep connections with Indigenous communities, who have a lot to teach people like me about what it's like to live in a place with harsh conditions, weather-wise, and the availability of water."

The concept of building self-reliance within a community taught him how to be a better global citizen. LaFontaine credits his summers with the program, Cottonwood Gulch Expeditions, for steering him toward a career in environmental advocacy. As agricultural policy manager for Friends of the Mississippi River, you can find him writing bills and advocating for better river health.

Looking back, he says he would be hard-pressed to think of a more transformative experience than summer camp. It gave him plenty of opportunities to test his personal limits, like climbing a 14,000-foot mountain.

"But you're also part of this lineage of people who love the place and cultivated a set of rituals and experience," he says. "It's not like you're being air dropped into a place where you're the only person. You're feeling what it means to be a human in this beautiful place."