Bill Alkofer, 61, perhaps the youngest resident of his St. Paul nursing home, reclined in bed, yawning his jaw for a routine dental check.

He had a question for the hygienist: Could she get him a fake tooth, to replace his missing canine? He wanted to record a video of himself, smile intact, to play at his funeral. But he didn't have much time.

"I'm going to die in, like, 2, 2 and a half months," Alkofer said, matter-of-factly, that March afternoon. "I'm not being embalmed," he added, "so it doesn't have to be perfect."

The hygienist said she couldn't promise anything. Making a tooth involved taking an impression, etc., etc. But she'd ask.

Alkofer frowned. He looked much the same as he always had: dark bushy hair, dark bushy eyebrows, longstanding uniform of dress shirt and tie that he wore on assignment for the St. Paul Pioneer Press and Orange County Register.

But Alkofer no longer dressed himself. After his body began showing symptoms of ALS (or Lou Gehrig's disease) about five years ago, he lost the ability to move his arms, then his legs. A few weeks ago, Alkofer lost what little mobility he had in his fingers, leaving him almost completely paralyzed.

But he wouldn't lose his sense of humor, even in life's final act.

He nodded toward the departing hygienist. "Five dollars Canadian I never hear from this woman again," he cracked, acknowledging the impolite truth: He was essentially helpless.

As a photojournalist, Alkofer spent his life coaxing other people — Gov. Jesse Ventura, a homeless guitarist, a girl who was allergic to sunlight — to let him document theirs. That's what motivated him to return the favor, letting the rest of us, so skittish about death and dying, witness the end of his life.

Alkofer invited a reporter and photojournalist to make regular visits, and watch his daily life — being fed, having a haircut. He let us interview his friends, family and death doula, and listen in on intimate conversations with nurses and clergy.

Most people choose to share such a vulnerable time only with close family and friends. But with a personality as big as his 6-foot-4 frame, Alkofer was never conventional.

He took a mannequin to his high school prom. And used a mug shot – taken after he'd climbed a water tower to get a photo – for his Christmas card. Close friends openly called him an asshole. ("But he's our asshole," they'd say with affection.) He planned a Monty Python-themed funeral with a Spam hot dish lunch, having already hosted 150-some friends and family at his "Awake Wake."

Alkofer hoped sharing his story would help others understand what it's like to live with death. He already had a sense of his own, particularly difficult, fate. Years ago, he'd watched his father die a long, awful death from an eerily similar disease.

As Alkofer saw it, his father's life had been torturously, unnecessarily, prolonged by a ventilator and feeding tube. He decided to make a different choice. At a time when Alkofer couldn't control anything, really, he remained determined to control his own death.

"Watching my dad go through what he did, and the pain that he suffered through, and that look in his eyes knowing he's going to die," Alkofer said, trailing off.

Photojournalism clicks

Alkofer was raised in rural North Dakota, near Grand Forks, where his first after-school job was with the Walsh County Press. Tasks included rewriting the wedding announcements and conducting person-on-the-street interviews that no one else wanted to do.

He thrived on connecting with people, but the toughest part was convincing the subject to let him take their photo. So he'd ask the person to turn their head or step into better light and say, "I guarantee you, this will be the best photo ever taken of you." And then, the secret: Take a couple of photos, set the camera down, and resume conversation. "After five or six minutes, then you take the real photo," he explained.

After graduating from college, Alkofer worked at newspapers in California and Minnesota, and rode life's ups and downs. Several times, he placed in Photographer of the Year competitions. But in the wake of a layoff and divorce (his two adult daughters live in Florida), he was homeless for a period.

Alkofer was the wacky uncle who once set fire to a toy car full of Barbie dolls and launched it into a river. ("This is not what normal people do, but I kind of like it," Alkofer's beloved nephew, Charlie Lang, remembered thinking.) Those who described Alkofer as obstinate, particular and attention-seeking, also called him an exceedingly charming, wonderfully generous, totally loyal friend. To have a conversation with Alkofer was to talk and laugh effortlessly for hours, bouncing between odd facts, wild stories and music references.

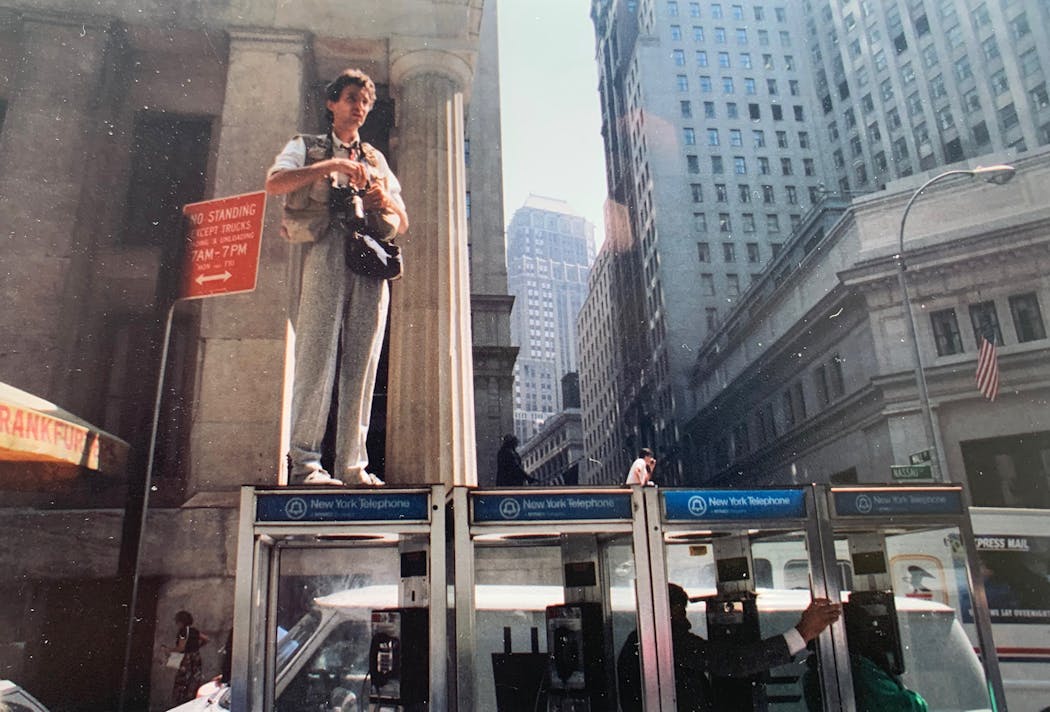

Known for his intensity and single-mindedness as a photojournalist, Alkofer pushed boundaries and bent rules. Sometimes that led to capturing an award-winning shot. (Wading into the 1997 Grand Forks floodwaters as firefighters worked to extinguish a blaze, for example.) Other times, losing a job. (Once, apparently, for defacing a Snoopy statue.)

Alkofer photographed high school sports as zealously as a Twins playoff game (when he wasn't banned from the ballpark) or the Olympics (where he slid down the Lillehammer bobsled track in a cardboard box). "It is a fun job," he said. "Oh my god, it's the greatest job to ever exist."

ALS arrives

Due to his camera's timestamp, Alkofer knew the exact moment he realized something was wrong. One October night in 2018, he was covering a football game when he went for an overhead shot of the crowd. He couldn't lift his arms.

Alkofer learned he had ALS, a disease with no cure. It causes patients to lose mobility in their limbs and, eventually, to be unable to talk, swallow and breathe. Life expectancy tops out at about five years.

At first, he worked around his limitation, using tools or momentum to help him maneuver. But by the time he left California for Minnesota in 2021, he was reliant on a wheelchair. Soon, the only part of his body that really worked was his brain.

"As the disease progressed, it was like, 'I can handle it,' " Alkofer said. "Now, it's to the point where the paralysis is such that I can't do anything. It kind of feels like being in a minimum-security prison."

Alkofer's father, Ray, experienced a similar decline due to developing multiple system atrophy, another rare neurological disease. Ray's condition was linked to his work degreasing airplanes with trichloroethylene (TCE), when he was in the service before Bill was born. There's no strong evidence connecting Ray's toxin exposure to his son's disease, but it is being studied.

Alkofer was motivated to share his story to raise awareness about TCE and help veterans and their families get the benefits they deserve. But he couldn't help wanting to influence the narrative.

"I want it to be a fun story, obviously," he said. "What's the best way we can write a story that will be about, you know, dying — because I'm a dying guy — but also make it a combination of educational and entertaining at the same time?"

Lost control

Alkofer never did get that fake tooth. Even after attempting to bribe the hygienist with his photographs of a mid-dunk Kevin Garnett and Tonya Harding at the Olympics.

Had he not been paralyzed, Alkofer would have shown up at the hygienist's office with a really cool print and left it on her desk. "Being a reporter is to know how to connect with people and get stuff done — and that's been taken away from me," he lamented.

The hygienist had suggested he instead stick a wad of chewed gum into the tooth-free spot. It felt like a metaphor for the best life could now offer: a tough, flavorless blob of gum in lieu of a uniform smile. Here he was: A guy stuck in bed who couldn't even drink his Grain Belt without a straw and someone to hold the bottle. (Adding insult to injury, the home staff doesn't serve alcohol.)

Using voice commands, Alkofer could make a phone call or turn on his fan. But with only minimal control of his head and neck, Alkofer spent much of his time directing visitors and staff to accomplish every minute task. He needed someone to arrange his pillows; adjust his thermostat; or fold his hands, now soft and waxy, across his chest for a nap.

Transferring Alkofer to a wheelchair involved two aides and crane-like mechanical lift. His hulking body, which once loped down a basketball court, dangled, limply, mid-air, in a sling. Once seated, Alkofer's ostomy bag needed to be tucked in; his feet repositioned several times. Even then, sitting could be so painful that it might be only minutes until he'd request morphine.

Surrounded by friends

In late spring, as plants bloomed, Alkofer withered. "You get the people saying, 'Oh no, no, you'll be fine, you're not going to die, you're going to fight this,' " he said. "I'm a religious person, but I'm also pragmatic. At some point — and it's started already — I'm going to have difficulty swallowing."

A few times, recently, when staff were feeding him, Alkofer had started choking, which was terrifying. When eating became impractical, Alkofer had decided he'd refrain from food and water to hasten his death. It would take, he was told, somewhere between a few days to a few weeks.

Outside Alkofer's window one day, a woman walking a dog wore a shirt that read: "Enjoy the miracle of being alive." (Alkofer's version of a slogan tee was a bib over his dress shirt that said: "Don't judge me. This dress was expensive.")

At this point, Alkofer's life didn't feel like much of a miracle. And he feared his final destination. Faith provided some comfort. As did his visions of his deceased dad. But having people around helped most.

Alkofer was hesitant to burden family and friends — "I think people are sick and tired of taking care of me," he said. But the many visitors he received, sometimes stacked up several deep in the hall, seemed not to mind. Alkofer continued to draw a crowd.

His regulars knew to slowly insert the straw into the Grain Belt, so as not to clog it with foam. And to give Alkofer the same grief they would have before his diagnosis — something he appreciated. "There are people I know who take everything so goddam seriously, and I try to do as little of that as possible," he said.

Alkofer's sister, Julie Lang of Excelsior, was the hub of his caregiving circle. Lang visited almost daily. Over the years, she had taken her share of midnight phone calls and bailed her brother out of bad situations, but she said it was well worth the effort. "He wasn't always easy, but you really couldn't help but help him," Lang said.

Alkofer worried people wouldn't remember him. Lang disagreed and told him so. "People all over the world have his photos on their walls, literally," she said. "He's going to be in people's minds for a very long time."

The end

Hospice workers are attuned to signs that a dying person has transitioned into their final stage. It's called the "11th hour," but can last for days.

On the afternoon of Friday, June 23, after friends visiting from California had left, Alkofer took a nap. In recent days, his condition hadn't markedly changed — he was still eating, if only a few bites — but he was sleeping more.

By evening, Alkofer's condition worsened. He made several calls, one after another, to Richard Marshall, his longtime friend from the Pioneer Press. But Marshall didn't have his phone with him. Marshall had visited earlier that day, and nothing seemed unusual. He had reassured Alkofer about his fear of dying, and resumed a mock-argument they'd had for more than a decade. After he saw Alkofer's calls, he alerted other friends and rushed over.

Cindy Benton, who lives close by, arrived at the nursing home first. Entering Alkofer's room, she said, "Hello, Bill," and immediately knew something was wrong. Alkofer, partially inclined in bed, didn't respond. She noticed two aides with tears in their eyes, who sat beside Alkofer, holding his hands.

Benton took Alkofer's hand. She told him he was loved, and that he would soon be with his dad. She wrapped his fingers around a rosary.

His breath and heartbeat were almost imperceptible. The room was quiet and calm. When the final moment came, a little after 9 p.m., Benton saw Alkofer's face relax. "It was just so peaceful," she said.

Lang and Marshall arrived soon after Alkofer died. The staff told them they could stay as long as they liked. When Benton and Lang eventually left, Marshall pulled a chair up to Alkofer's bedside, to be with him, Marshall said, as his spirit passed.

He fixed Alkofer's hair, straightened his shirt, and took one last photo of his hands. And then he sat, keeping vigil over his best friend's body, continuing their conversation until 2 a.m.