’70s

Defiant beginnings

1970-1979

Jean-Nickolaus Tretter: It was a time for movements — the African American movement, the women’s movement. The Stonewall Riots [in June 1969 in New York’s Greenwich Village] were a kind of signal that we were going to have our own movement.

Michael McConnell: The term “gay pride” was invented here. Thom Higgins had been raised in the Catholic Church and decided to come up with a means of countering the negative energy coming out of the church. So he paired two of the deadly sins: gay and pride. That language was transformative. It is one of those things that opened the door and moved people forward. Jack [Baker, McConnell’s husband] went down in 1971 to Chicago, where he had been invited to speak, and took the term “gay pride” there. And the explosion began.

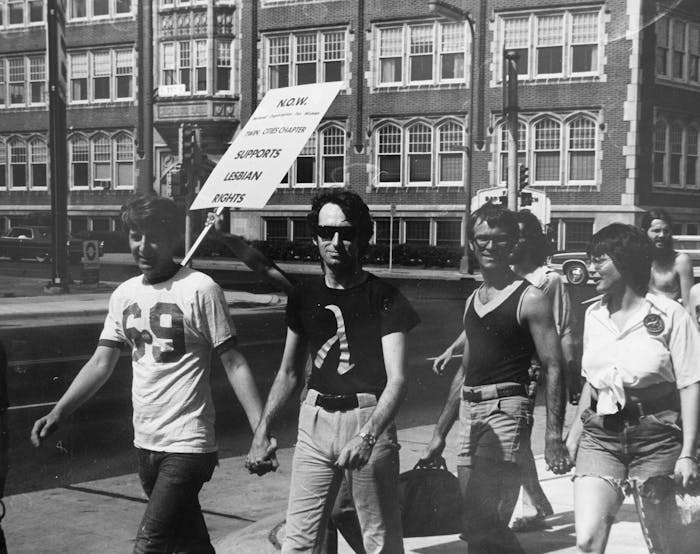

Jack Baker, left, and Michael McConnell held hands as the 1974 Pride march made its way to Loring Park. (University of Minnesota Libraries, Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection)

Tretter: Jack Baker had been elected as student body president at the University of Minnesota — the first openly gay student body president in the United States. Chicago made him grand marshal of its march. So we said, “If Chicago can do it, we have to have a festival here.”

In June 1972 we decided we’d have a picnic in Loring Park and then walk down Nicollet. We didn’t know what would happen, so we divided the 50 people into two parts: Twenty-five stayed in the park with all the money so they could get us out of jail if we were arrested for being gay. Then the other 25 of us went down to Nicollet Mall and 4th Street. It was much more of a march than a parade.

Jean-Nickolaus Tretter

Established an LGBTQ studies collection at the University of Minnesota

John Moore: There was just a handful of us. Most watched from the side. They were afraid of the police. That first parade, now that meant something. Even though they didn’t want us there, we were showing them that we were there. Now, everyone wants to be a part of it.

Julie Dafydd: I can tell you exactly what I was wearing. I wore my knee-high brown suede moccasins, my matching fringe vest with a suede headband, a Mickey Mouse T-shirt and cut-off jean shorts.

Tretter: Nobody really bothered us because they didn’t understand what we were trying to do. We were saying “gay and proud” and everyone thought we were talking about being happy.

Lisa Vecoli: The second year, in 1973, the Pride program was one page, a 10-inch square, handwritten on both sides, designed to be folded so it could be flicked like a Frisbee. There was a sense that people might be confronted by law enforcement and harassed. So it was designed to be tossed.

Lisa Vecoli

Founder of the Minnesota Lesbian Community Organizing Oral History Project

Meadow Muska: Many lesbians, we had been marching for everybody — for children who are hungry, Native American rights, African American rights. There was a lesbian resource center at that time and some very brave women held it and we marched for all social causes. It wasn’t just one focus.

Claude Peck: It was all very grassroots. I got involved because my old boyfriend Bob Bruneau became the treasurer of Target City Coalition, a 1970s activist group formed to combat antigay crusader and orange juice spokester Anita Bryant. She had targeted St. Paul as a place to try to win the repeal of an early gay rights ordinance.

Anyone who was a Target City Coalition regular was duty bound to help out with Pride, which had been more like a march and a protest rally, and then it evolved. The political component was still there, but it was fun, it became a celebration, a time to socialize, see old friends and make new ones. That’s what I’ve always loved about Pride, feeling that web of connection.

McConnell: Those first years were celebrations. It was proud people holding signs and saying: Yes, we’re here, and we’re good.

Beginnings of Pride

’80s

Battles won and lost

1980-1989

Tom Burke: Our attitude was that Pride was inherently political. But we wanted it to be something people wanted to come to. We wanted a beach party down by the river, which was a cruise-y area, the river flats down there, south of Franklin Avenue. We scheduled it on the day before the parade, and quickly learned that was wrong because everyone was so hung over and sunburned that nobody showed up the next day.

Tretter: Other festivals charge to get in. In Minnesota, people wouldn’t come if they had to pay. We tried it one year — charged a dollar to go to the festival. People went back to where they parked.

Peck: We raised money back then by selling $2 Pride buttons. The themes included “An Army of Lovers,” that was from Walt Whitman. “Cruising Into the ’80s” was the most controversial; a lot of people hated it.

Burke: At one point, Brad Golden said he wanted to have a block party on Hennepin Avenue. I said, “They’re never going to give us a permit,” and he said, “Why not?”

Peck: We filed for a block-party permit in 1980 and the Minneapolis City Council turned it down, which was a slap in the face, because the city had closed Hennepin for other groups. Later that year, we sought a permit for 1981 Pride, and that was also turned down. Some on the City Council opposed the permit because of traffic and crime issues. Dennis Schulstad, who was the most conservative, gay-hating member, opposed it on moral grounds. Council President Alice Rainville famously said, “This will turn Minneapolis into the San Francisco of the wheat belt,” and we were like, “Yeah, that sounds good.”

Walt Dziedzic, Minneapolis City Council member, speaking in 1981: People with six kids like me fear that lifestyle. They fear their children might be converted to that lifestyle. It sends a message that Minneapolis is a gay town.

Peck: The Gay Pride Committee went to the Civil Liberties Union, which sued the city of Minneapolis in U.S. District Court. The judge was Miles Lord.

Burke: We were skeptical any judge or city council was going to give us a permit until the case got assigned to Miles Lord — randomly, I think. He was known as a very liberal judge. So we were like, “Oh my god, we may have to actually put on this block party.”

Judge Miles Lord in 1981: Those who wish to promote gay rights have a constitutional right to do so.

Claude Peck

Board president of Quatrefoil Library

Peck: All of a sudden, we had a permit, for one hour, between 8 and 9 p.m., for the block on Hennepin between 4th and 5th streets, in front of the Gay 90s and the Sun Disco. We thought it might be impossible to pull something off in that time frame, but we decided that we had to do something or lose face.

I went to Hiawatha Rental and got a flatbed truck, and we basically lashed all the equipment for the Urban Guerrillas — a post-punk pop band — to the truck. I’m barely able to drive this truck, and I’m hoping that I don’t flip the band right off the back of it. When I turned the corner onto Hennepin, I saw that there were almost a thousand people in the street, and then the crowd just kept getting bigger and bigger. I just freaked out.

The band plugged in — we ran extension cords from the Gay 90s — and started playing. There were speeches by Matt Stark [of the Civil Liberties Union] and Brad Golden [of the Pride Committee], and some drag queen performances, and before you knew it, the hour was up, and it was over.

In 1982, the Pride Committee removed “Lesbian” from the event’s title, so women held an alternative Lesbian Pride in Powderhorn Park, near the so-called “Dyke Heights” neighborhood. The festival became Gay and Lesbian Pride again in 1983.

Vecoli: There was tension — pretty much from the start — between the gay male community and the lesbian community. Women felt like they weren’t represented in the existing Pride organization.

Lori Dokken

Music director, vocalist, pianist and producer

Lori Dokken: I remember sitting on a hill in Loring Park with a picnic basket. There were maybe 200 people. There was a stage, with folks playing guitar and singing, maybe two or three people spoke. It was very chill, and I thought it was swell, especially because I’d grown up in a small town. Benson, Minn., was a pretty isolated place in the ’60s and ’70s, and now I was sitting with other gay people in public at a Pride event.

In the beginning, there was one stage, and it was a pianist and a vocalist. It expanded from there, to a stage band with a full-on horn section and six girls singing up front. And it was always me saying to people, “Hey, will you come sing for free? And haul all of your gear? Oh, and by the way, there’s no place to park.”

Vecoli: What I remember from my first Pride, the part that’s so visceral to me, was walking across the pedestrian bridge into Loring Park — the sense of freedom I felt. Throughout the day, I put on the buttons and the arm bands. And at the end of the day, you had to cross back over the bridge. As you did that, that sense of safety and inclusion and visibility fell away. All of a sudden you weren’t safely visible — you were exposed. I remember walking across the bridge and taking off the buttons, taking off the arm bands and disappearing.

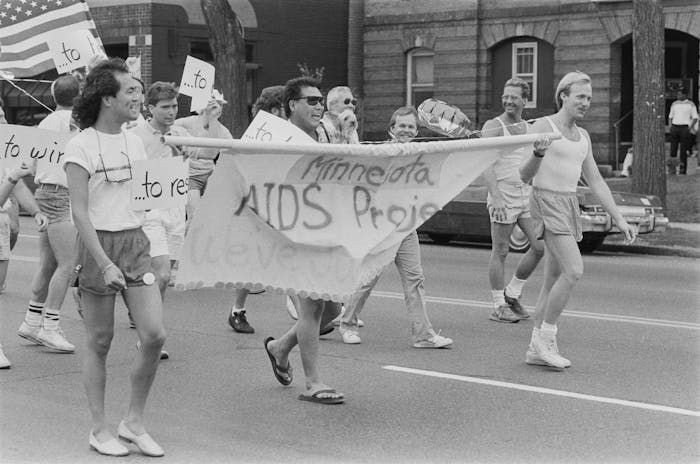

Marchers in the 1986 Pride parade carried a banner for the Minnesota AIDS Project, a grassroots effort founded by gay volunteers that galvanized the state’s public-health response to the HIV/AIDS crisis. (Minnesota Historical Society)

By 1983, AIDS had become a topic of alarm even though only a handful of cases had been confirmed in Minnesota. Half of the proceeds from that year’s Pride Week were pledged to an AIDS medical fund.

Brian Jones, editor of the gay newspaper Equal Time, in a 1983 interview: It’s all you hear talked about where gay people meet. Some people are just plain panicked. We were finally making some progress, gaining some acceptance. Suddenly, out of nowhere, comes the mystery killer that is striking us down.

Moore: People were being murdered in Loring Park. People were dying of AIDS. We had wakes on the Saloon's dance floor, because funeral homes wouldn’t have people with AIDS. There was a network of underground gay funeral directors, and they would come to us. Those bodies of people with AIDS, they blessed our space. That’s the story of gay Pride.

Dokken: In the early years of HIV/AIDS, when we were raising awareness about being more open, and being more out, that’s when everything really took off.

’90s

Growing acceptance

1990-1999

By 1990, the event had grown so large that it began requesting vendor applications. Trans activist Ashley Rukes — now the namesake of the Pride parade — became festival director.

Burke: Ashley had been in charge of the Aquatennial, so she brought her Rolodex. That’s when the parade really took off.

Ashley Rukes, speaking in 1993: The parade had traditionally been rather free-for-all. They lined up on that street on Sunday morning — first-come, first-to-march. In the past several years, we’ve organized ourselves. We are meeting one another now. I just love to introduce people and get people going. We have brought people of color, youth. I think we’re seeing the beginnings of a real wonderful community.

Dafydd: For the amount of people that show up, it’s so peaceful. It’s turned into a celebration — not that there isn’t plenty more to be done.

In 1992, Tretter debuted the History Pavilion in Loring, with displays covering “4,000 years of gay and lesbian history.”

Tretter, speaking in 1992: It’s important we create a historical legacy to pass along to future generations. It’s how the Jews endured thousands of years of persecution, because they had a tradition and a history. I would like to have a part in giving gays and lesbians of the future something similar to hold on to.

Attendance reached 50,000 in 1992, doubled that by 1995 and hit 200,000 in 1998, according to the Civil Liberties Union, as corporate sponsors began coming aboard.

Dokken: It was 1994, and state Sen. Allan Spear and I were the Grand Marshals. His partner was shy and reticent to ride in the parade. So was my partner, Kate. Allan and I talked them into getting into the car with us. It was a white convertible. It was a sunny day, there were a lot of people and I was just amazed. The back of my head hurt from smiling for an hour and a half.

Then it was over, and it was time to run to the stage in Loring Park and set up. That brings you back to earth, because one minute you’re smiling and waving and the next you’re hauling stuff. The glamorous side of the entertainment business, right?

A mother offered her support during the 1992 Pride Festival at Loring Park. (Jeff Wheeler, Star Tribune)

Vecoli: I think my favorite Pride has to be the march where my now-wife and I marched with all four of our parents. That was something I don’t think we ever thought we would get to do. My wife, Marjean, grew up in Wisconsin. Her father was a Methodist minister. Her mother was a schoolteacher. My father was a professor at the U and my mother was a teacher.

What is their reaction going to be? And, you know, I was so proud of them. They were fine. We marched with PFLAG [Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays] and it was pouring rain. We were wearing garbage bags. We got drenched. You would see people on the side of the road crying. And I think we were crying, too. We felt like the luckiest people at Pride that year because we had the acceptance of our families.

Dennis Anderson: Twenty years ago, Pride wasn’t so inclusive. So we decided to come up with our Black Pride in 1999 to set a different tone. To make sure all cultures are included. Your food. Your ethnicity. People like you onstage. We did a boat ride, a picnic in a park, a night of partying.

This has continued now for two decades in some fashion. This is my calling — letting people know that you don’t have to suffer. You can be yourself and come out. That is what Pride does every year. For the last 20 years, it’s helped me grow and a lot of my friends grow.

How would you describe Pride?

’00s

New beacons

2000-2009

Beverly Little Thunder became the first Native woman to be Grand Marshal in 2001: It was a great honor. My granddaughter Aris, who was 10 at the time, rode in the parade with me. She was so excited. As a side gig now, she does makeup for weddings. She told me: “You know where I learned to put on makeup? From the gay boys in Minnesota!”

For me, it was an opportunity to share with a generation in my family that this was OK — that this was something to be celebrated. I never dreamt I would see something like that happen in my lifetime, much less that it would be me in that position. After that, my mother had a whole different take on my being gay. People were coming up to me at powwows, in the grocery store, on the street. “I remember seeing you in the parade! You don’t know how much that meant to me.”

I was like: Wow, you never know who you impact. The Pride parades do that, sometimes in subtle ways we’re not even aware of. It’s a gift when we become aware that something we have done has impacted another person, especially another person in the next generation.

Beverly Little Thunder, center, became the first Native woman to be Grand Marshal in 2001. (Photo by Sophia Hantzes).

Roxanne Anderson: The Power to the People area in Loring Park was a response to discrimination. In 2000 I was tabling with an organization called Minnesota Men of Color (MMC), and on a stage very near our booth there was a trans woman of color performing. Midway through her song, the DJ cut the record. She came marching to our booth: “We keep getting kicked off the stage, and I’m sick of it.”

We took that as a challenge. [MMC co-founder] Nick Metcalf had us show up at Pride board meetings. They didn’t take us seriously at first. They didn’t have an understanding of why we needed something that was about just us. The very first year, we got 20 different organizations serving people of color to show up in our area. We had 24 artists, groups or acts performing cultural music, relevant content to communities of color.

Dennis Anderson: It became a beacon in the park. The rest of Pride is basically Caucasian, so that area is making sure you have a voice.

Dot Belstler, executive director of Pride since 2009: I’m a straight, white soccer mom from Anoka. What is this person doing running Pride? It’s something I care deeply about. I have close friends in the community. I’m the ally — I’m the “A” part [of LGBTQIA], how’s that? Pride was a bit of an old boys club. Really, the board was made up of gay males. We’ve really worked to diversify that.

Dokken: In the 2000s, I noticed that there was a lot more corporate sponsorship coming in, and that’s when I went, “Huh, I don’t know if I like all this corporate stuff.” I missed the picnic basket on the hill. But as the years went on, I realized that it was great, seeing all of the organizations of all kinds — and communities of all kinds, and families of all kinds — getting involved and having a great time together. A minority group can make noise and fight for its rights, but it’s when our families and our neighbors get involved, that’s how we can take turns advocating for each other. We’re not alone. We’re all in this together.

Jana Shortal

KARE-11 host

Jana Shortal: My first reaction: There are this many gay people? Kind of like, excitement, overstimulation — probably how a 5-year-old reacts to Disney World the first time. In my early years I didn’t know enough about it — it started at Stonewall, it was a riot and it wasn’t a parade where there was candy and everyone was happy. There was brutality and retaliation and fear. Most of us live in our own lives that get us to our own point of coming out safely. In the beginning, I just wanted to be me.

Xochi de la Luna: Before I dug into the history, it seemed like this big corporate festival for gay white men and, yeah, sure, lesbians, but it seemed overwhelmingly white, and always the cop presence turned me off.

Dennis Anderson: This is America. If we don’t have those funders, how do we have a free Pride? The city charges us for the police, for the park. Who pays for that? We are a nonprofit. If we don’t have Target to make sure this happens, we don’t survive.

Challenges facing Pride

’10s

Marching on

2010-NOW

Shannon TL Kearns: I was at a booth for the church that I was serving at the time, and we had this banner that said, “A Catholic Church That Welcomes All.” People were so shocked to see a Catholic community at Pride. There were a couple folks who came up and couldn’t say anything. They were just crying.

To stand and witness that and to hug them and let them know how loved they are was really profound. For folks to say, “I didn’t know I could be and do this.” Just to be able to say, “You can.” You can be both queer/trans and a person of faith. It’s not like you’re Christian in spite of your transness. These two things can give life to each other and profoundly challenge one another.

Shannon TL Kearns

Playwright and theologian

Xay Yang: For me, the Power to the People stage is the highlight of Pride — that little corner, filled with people of color. In white, gay culture, we experience so much racism, and coming into our Hmong community, we can experience homophobia. On that stage, Hmong folks would do drag, they’d sing in Hmong, they’d play Hmong instruments, they’d do skits that were gender-bending. Omigod, to embrace all the queerness and the Hmong-ness together!

Roxanne Anderson: The talent that has been on that Power to the People stage! We’ve had Chastity Brown, we’ve had Lizzo, we’ve had Frenchie. All kinds of local artists and activists. The list goes on and on. We get the great fortune to play host to them for five minutes or 30 minutes, and that makes us — LGBT folks of color who are sitting the hill — feel really good. We have had Lynx players come and hang out. We have had mayors come and hang out. Some have been welcomed, some haven’t.

Roxanne Anderson

Created Power to the People stage at Pride

Belstler: In 2012 the marriage amendment [to ban same-sex marriage in Minnesota] was going to be on the ballot. I remember going to [the advocacy group] OutFront and saying, “How can Pride be a vehicle to help get this message out?” We turned Pride orange that year. Everything was “Vote No.”

Then in 2015, the Supreme Court declared that the Constitution guarantees a right to same-sex marriage. This was the Friday before Pride. That was just so fun. So many people were there. It was like the world came out.

T.J. Danielson, interviewed that day among the hundreds of thousands on Hennepin: Truthfully, I never thought I would see it in my lifetime. [In past years] Pride was the safest place you could be. You couldn’t do it any other time of the year. It’s about time they actually took the sex out of it and realized it’s just love.

Andrea Jenkins

Minneapolis City Council President

Andrea Jenkins, who led that 2015 parade: Oh my goodness, being Grand Marshal was huge. It felt like I was being seen and acknowledged and recognized for my service to the community. It felt like trans voices were being uplifted and recognized. This was right at the beginning of the recognition that so many trans women of color were being murdered. We staged a die-in to bring awareness and attention to that issue.

I had a convertible, and the people with me — mostly trans or nonconforming, people of color — were on bikes and scooters. Once we got to the stage at 8th and Hennepin, we all got off our bikes and scooters, and I got out of the car.

Yang: They paused, and everybody marching with Andrea fell to the ground. Wow. In the parade, you see a lot of politicians, businesses; it’s become less about community. To see somebody do that — to make that kind of statement — was really powerful.

Jenkins: It was a nod to the fact that Pride has always been about advocacy and direct action.

The festival and parade was canceled in 2020 but the murder of George Floyd brought hundreds to Loring Park anyway.

Roxanne Anderson: Even when Pride said we’re not gathering because of COVID, people still came. People performed. People danced. There were still people protesting, still demanding justice, still reminding us that we would not have Pride if it wasn’t for Black and Latinx trans women of color.

We forget that when we’re in the club, dancing and shaking our booties and looking our best dusted in glitter. And that’s OK; we don’t have to protest all the time. But we have to remember that the reason we come to Pride is because of police brutality, because of discrimination, because of state-sanctioned surveillance.

The first Pride was a riot. Without people saying: I’m not going to tolerate violence against my person or my body any longer, and I’m going to stand up and fight back, we wouldn’t gather 400,000 people dancing, drinking, wearing beads, doing their best Beyoncé impression onstage. That is the real essence of Pride.

Jenkins: These public displays of Pride and community are so important for our young people who are coming out as gender-fluid, gender-nonconforming at a time they’re being attacked and vilified in our nation.

Hannah Edwards, mother of a trans child: When Hildie was 3, she chose to wear this Superman cape and a Princess Merida wig to Pride.

Hildie Edwards

actor/performer

Hildie Edwards: I just remember all these fabulous people walking down the street. And I loved it.

Dave Edwards, Hildie’s father: After Hildie transitioned, she had a streamer and she danced the entire route of the parade. Seeing her be celebrated and feel all the love that was around her ...

Hannah Edwards: And seeing the joy that people watching the parade were drawing from Hildie! Which of course made my heart explode.

Dave Edwards: I think we’re at a particularly scary moment with a lot of legislation and the attacks on trans kids. So I’m hoping we’re taking a turn towards affirming LGBTQ+ youth: “You’re seen and you’re loved. No matter what’s happening in your school or your household, there are people that are gonna be here for you.”

Older folks in the queer and trans community are like, “Oh, it’s Pride again.” But for a lot of our young people, this is the first time they’ve seen anyone who reflects who they are. And that’s always going to be special — and so needed at this moment.

Looking to the future

Contributors

to this oral history

Dennis Anderson, 54 (he/him), founded the Minnesota People of Color LGBT Pride and is a member of Twin Cities Pride’s board of directors.

Roxanne Anderson, 53 (they/them), a community organizer and activist, created the Power to the People stage at the Pride festival, which is celebrating 20 years this month.

Dot Belstler, 63 (she/her), is the executive director of Twin Cities Pride. She is retiring this year.

Tom Burke, 75 (he/him), is a longtime gay rights activist and attorney who helped create many of the events still celebrated as part of Twin Cities Pride.

Julie Dafydd, 70 (she/her), is an actor, writer, accidental activist and hopeless fashionista. A self-described “worker bee,” she raised money and planned entertainment for Pride.

Xochi de la Luna, 31 (they/she), is a multidisciplinary artist and event producer whose work focuses on the cross pollination of the arts. They live in Minneapolis.

Lori Dokken, 62 (she/her), is a music director, vocalist, pianist and producer. She lives in Minneapolis.

Hildie Edwards, 11 (she/her), is a transfeminine and nonbinary actor/performer who advocates for affirmation and celebration of trans kids. Hildie’s parents Dave and Hannah Edwards fight against gender-based bullying and discrimination in schools.

Andrea Jenkins, 61 (she/her), became in 2017 the first African American openly trans woman elected to public office in the United States. An artist, poet and activist, she is now president of the Minneapolis City Council.

Shannon TL Kearns, 41 (he/him), is a playwright, theologian and ordained priest who has written a memoir about being a transgender man, due in August.

Beverly Little Thunder, 75 (she/her), is a Lakota elder, women’s activist and member of the Standing Rock Band from North Dakota.

Michael McConnell, 80 (he/him), and husband Jack Baker made history when they became the first same-sex couple in the country to apply for a marriage license in 1970.

John Moore, 72 (he/him), has co-owned the Saloon, a gay bar in downtown Minneapolis, since 1980.

Meadow Muska, 69 (she/her), is a photographer and retired master electrician. She splits her time between Minnesota, Florida and the rest of the world.

Claude Peck, 66 (he/him), was an editor at the Star Tribune, Twin Cities Reader, Q Monthly and Mpls.St. Paul. He is board president of Quatrefoil Library, an LGBTQ+ resource center in Minneapolis.

Jana Shortal, 44 (they/them), is host of KARE-11’s “Breaking the News.” They live in Minneapolis with their wife, Laura, and 6-month-old child.

Jean-Nickolaus Tretter, 75 (he/him), established the Tretter Collection in Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies at the University of Minnesota, the largest LGBTQ+ collection of its kind in the Upper Midwest.

Lisa Vecoli, 59 (she/her), is curator of the Tretter Collection and founder of the Minnesota Lesbian Community Organizing Oral History Project.

Xay Yang, 32 (she/her), serves as the queer-justice director at Transforming Generations, an organization focused on ending gender-based violence.

Jenna Ross was the lead reporter, with contributions from Alicia Eler, Chris Hewitt and Rick Nelson, videography by Shari Gross and photos by Aaron Lavinsky. Tim Campbell was the project editor and Christine Nguyen the photo editor, with research help from reference librarian John Wareham. Anna Boone designed the digital edition and Mike Rice the print section. Assistant Managing Editor for Features Sue Campbell supervised this project.