In Harm's Way

This four-part series explores how Minnesota’s child protection system failed to save some of the state’s most vulnerable residents.

Every year, Minnesota judges remove thousands of endangered children from their parents' care. They often do so after county workers have documented horrific acts of abuse and neglect.

Most of those children are eventually sent back home.

Some don't survive the reunion.

A 2-year-old girl was beaten to death by her mother when she wouldn't stop crying at bedtime.

A 17-year-old girl died by suicide after enduring years of physical and sexual abuse by her parents.

A toddler approaching his first birthday died from an overdose of fentanyl and methamphetamine in the back seat of a stolen car after his father fled the scene.

At least 15 children have died from maltreatment or by suicide during the past decade after being reunited with their caregivers, records show.

Hundreds more endure brutal beatings, sexual abuse and other forms of maltreatment after judges send them back into harm's way in the care of their parents.

Minnesota has repeatedly failed to meet federal benchmarks that measure a state's ability to successfully reunite troubled families — drawing threats of government sanctions.

Kathleen Blatz, the former chief justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court who served on a state task force that in 2015 recommended nearly 100 child protection reforms, said too many children are being harmed because the system is focused too much on helping the abusers and not protecting the abused.

"We've got this system now that I think has elevated family preservation and parents' rights over children," Blatz said. "And the child pays the price. … If we ever did to domestic abuse victims what we do to children, there would be such a hue and cry."

In some cases, families are reunified despite warnings from relatives or county workers. Even parents who fail drug tests, skip therapy or engage in new criminal behavior are getting their kids back.

The Star Tribune spent more than a year examining Minnesota's child protection system after 6-year-old Eli Hart was killed by his mother last year in a case that drew international attention.

Julissa Thaler was convicted of first-degree murder in February and sentenced to life in prison for shooting Eli nine times and then stuffing his body in the trunk of her car. Eli's death came 10 days after a Dakota County judge granted Thaler full custody of the boy.

Court records show that Thaler failed to attend court-ordered mental therapy, was kicked out of a required parenting class and had to find a new drug-testing facility because of her "bizarre behavior."

Though county workers repeatedly raised concerns about Thaler's actions, they ultimately recommended that she be reunited with her son after she consistently tested negative for illegal drugs and agreed to start seeing a therapist.

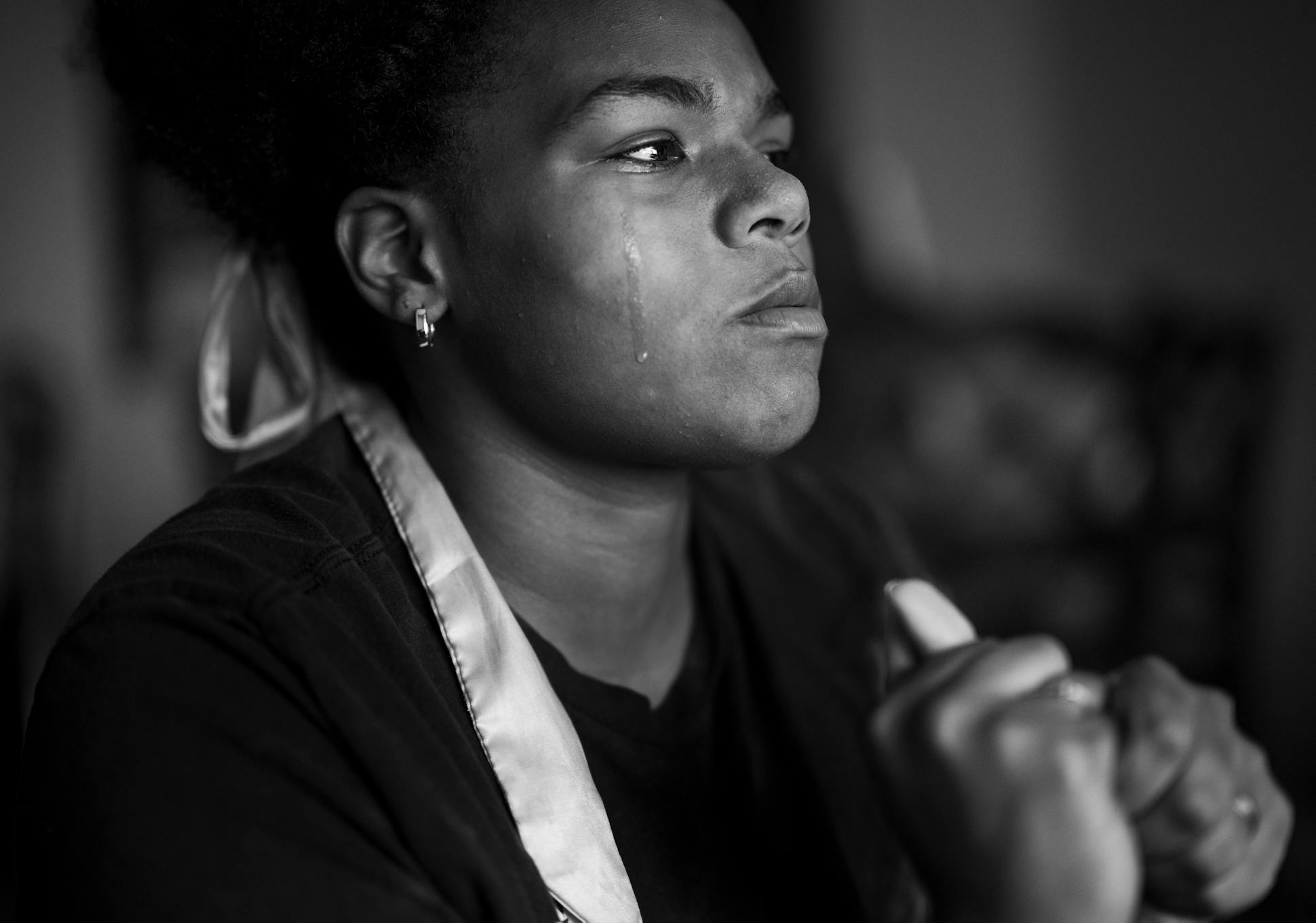

Heaven Watkins

Sheronda Orridge said her warnings also went unheeded in 2016 when a Ramsey County judge agreed to return her 9-year-old niece to her mother, Latoya Smith. The county had just gotten a report that the girl, Heaven Watkins, had been hit in the face while on a trial home visit. Heaven, who had cerebral palsy, had been removed from the home after prior incidents of physical abuse.

"I actually told them if you let her go back to her mom, she is not going to live long — and the blood is going to be on your hands," Orridge said.

Heaven was beaten to death 19 months later by her mother's boyfriend after the family moved to Virginia. Smith pleaded guilty to homicide and felony child abuse. She admitted to multiple incidents of abuse involving Heaven, whose body was found with 24 bone fractures in various stages of healing.

In a written statement, Ramsey County officials expressed their "sincerest condolences" for Heaven's death, calling it a "tragedy," but declined to answer questions about the case or the county's child protection practices.

"Removing a child from their family doesn't guarantee safety," Ramsey County officials said in the statement. "It is a tool, utilized when it's determined with thorough assessment when safety cannot be established in the child's home setting. Data shows that children are more likely to experience significant trauma when they are removed from their homes."

Nikki Farago, a deputy commissioner at the Minnesota Department of Human Services, said the department is looking "seriously" at how to reduce the levels of abuse that take place after reunification.

The fatalities, she said, are "very small numbers."

"Many times, when we have a tragic death, you want to know what went wrong and you want to go to quick fixes," Farago said. "And so many times those quick fixes don't really address the problem."

Children still in danger

Reunification is supposed to be the last step in an often twisting legal road that begins with someone, often a teacher or doctor, calling in a report of abuse or neglect to the county.

In Minnesota, most abuse and neglect reports lead nowhere. In 2021, the last year for which data is available, county workers screened out about two-thirds of the nearly 80,000 referrals they received for child protection. Only five states screened out more, federal records show.

Minnesota's ability to determine which cases merit further action hasn't improved much since 2014, when the Star Tribune published an investigation of the death of a 3-year-old boy named Eric Dean.

Before Dean was killed by his stepmother, caregivers and family members reported at least 15 incidents of abuse. The boy sustained a broken arm, bruises, scratch marks and bites over his body. Nine of the calls were screened out, meaning no action was taken, and the only report that was investigated resulted in a finding of no maltreatment.

The Star Tribune's reporting prompted then-Gov. Mark Dayton to form a task force that recommended sweeping changes to the child protection system. Though state officials adopted some, such as beefing up training and creating new intake guidelines to address screening decisions, Minnesota children are not better off.

A dozen children with a child protection history died from maltreatment in 2021, the second-highest figure in at least a decade. The number of repeat abuse victims is also up by 60%, with Minnesota's rate now more than twice the national average, federal records show.

Since 2012, at least 86 children died from maltreatment after Minnesota's child protection system failed to protect them from caregivers with a history of abuse or neglect, records show. Another 11 children died by suicide after a child protection case was filed on their behalf, including a 6-year-old girl.

Lucinda Jesson, a former commissioner of the Minnesota Department of Human Services who helped craft the recommended reforms, said the data suggests it's time for the state to yet again re-evaluate its approach to child protection.

"We were very explicit that we needed to readjust the pendulum," said Jesson, who until recently served as a judge on the Minnesota Court of Appeals. "There are some things where I see real progress. But the numbers really cause me to wonder if what was implemented did the job we wanted it to do."

To reduce abuse, the task force urged the state to impose a limit on the number of cases handled by overburdened child protection workers and boost state funding to cover those costs. But no limits or new funding streams were created, and county supervisors say they still have workers who handle as many as 20 cases at a time — twice the maximum recommended by the task force.

"Bad things are going to happen because we don't have a well-funded child protection system in Minnesota," said Judith Brumfield, a task force member who supervised child protection services in Scott County until 2015.

Returned too soon

Under state law, the aim in every case is to reunify children with their caregivers "at the earliest possible time." Typically, about 60% of the cases end in reunification each year.

The goal, according to child protection workers, is to avoid the trauma children experience when they are removed from their parents, and their homes, for extended periods of time. The consequences have long fallen hardest on Black and Native American families, whose children were removed at disproportionately high rates.

But reunification is not supposed to occur until parents have addressed the problems that prompted judges to remove their children.

In 18 cases involving fatalities, records show judges approved reunifications despite warnings from family members or county workers, or when parents had failed to obtain required therapy and other services.

For instance, a Hennepin County social worker reported in 2021 that she was unable to obtain a mother's recent drug tests or reach her treatment counselor for an update. A judge allowed the mother to regain custody of her son anyway. Two months later, the boy — who had been removed from home shortly after birth because of his mother's drug use — died from an overdose of fentanyl and methamphetamine. The county blamed his mother for failing to protect the infant.

Kelis Houston, co-chair of the Minneapolis NAACP's child protection committee, said the state needs to find a way to identify higher-risk situations and remove children when they are in harm's way. Too often, she said, child protection agencies in Minnesota are overwhelmed by low-level neglect cases involving poverty-driven problems such as inadequate clothing.

"I don't think we're punitive enough when there's actual abuse," said Houston, who also represents children in protection cases as a guardian ad litem. "If you're sadistic enough to shoot your child and put him in the trunk, or if you're sadistic enough to chain your child to a bathroom sink over the course of months, do you really think a parenting assessment or a psych evaluation or UAs [drug tests] — which is the case plan for all of our families — is going to address that? It doesn't."

Federal records show 552 Minnesota children suffered maltreatment in 2021 after being returned to their caregivers, up from 345 incidents of re-abuse in 2014.

As a result of additional abuse and neglect, nearly 13% of Minnesota children who were returned to their parents were subsequently removed again over safety concerns in 2021, well above the federal standard of 8.3%.

"Minnesota has among the highest rates in the country of failed reunifications," said Sarah Font, an associate professor at Penn State who specializes in child protection issues. "Minnesota seems to be rushing those reunifications — or reunifying when it is not appropriate."

Minnesota is one of nine states in which child protection services are administered by county agencies. The state Department of Human Services (DHS) provides oversight.

The DHS monitors county performance on various benchmarks, including how often children suffer substantiated maltreatment within 12 months of a prior determination of abuse or neglect. Since 2018, public records obtained by the Star Tribune show 36 counties failed to meet the federal limit on repeat abuse, most more than once.

While the DHS routinely warns counties that "fiscal penalties may result if performance does not adequately improve over time," the state did not impose any financial sanctions on the counties for violating the repeat abuse standard.

By contrast, federal regulators threatened to withhold more than $500,000 in aid for Minnesota's repeated failure to meet the standard for successful reunifications.

"DHS prefers to work collaboratively with counties to improve their child welfare outcomes in lieu of imposing financial penalties," an agency spokesperson said in a written response to questions.

Counties are supposed to file a child mortality report every time a child dies from maltreatment or if the child dies from homicide, suicide, an accident or undetermined causes. The reports are supposed to help guide improvements to child protection.

But a Star Tribune survey of more than two dozen counties shows that compliance is spotty. Some counties fail to conduct required reviews; others take years to complete them.

Farago said she could not think of a single policy or procedure that changed as a result of the mortality reviews in the past five years.

Yet researchers say a single death can reveal important shortcomings in a state's child protection efforts.

"For every child who dies because of a series of systemic failures or poor decisions, there are easily 100 children who experienced the same processes and have not yet died — but shouldn't be in the position they are in," said Emily Putnam-Hornstein, a University of North Carolina professor who has consulted on child protection reform in California, Colorado and Pennsylvania.

The Star Tribune requested interviews with the leaders of child protection agencies in 26 counties that had at least one fatality in the past decade, and all but three counties declined the offer or did not respond to the request.

Don Ryan, who has served as Crow Wing County attorney for 28 years, said the pendulum has swung too far in favor of parents' rights. The shift came in response to complaints that the system was overzealous, with children sometimes languishing for years in foster care.

"I remember when Crow Wing social services would initiate court actions for dirty kitchens," Ryan said, noting that such cases would merely open the door to social services today. "But if everyone is looking over their shoulder, wondering if we are being too aggressive, that is not a good thing either."

Anoka County Attorney Brad Johnson disagreed, saying he believes Minnesota has struck the right balance between protecting kids and preserving families.

"Every experienced social worker or child protection lawyer has lost one or more cases where children remain in or are returned to what was considered a dangerous environment," Johnson wrote in response to questions. "From the government's standpoint, that was the wrong outcome. Sometimes from the standpoint of the court, the guardian ad litem or the parents, that was the correct outcome. It can be a matter of perspective."

'All about reunification'

There are no limits in state law to who can get their children back. Among the Minnesotans who have retained or regained custody of their children: parents convicted of second-degree murder, kidnapping and malicious punishment of a child.

In 25 cases involving children who died, records show that parents who were wholly or partly blamed for causing the death of one child were later allowed to regain custody of surviving siblings. One of those parents, who was convicted of manslaughter for not seeking medical attention for her 17-month-old son after he was seriously injured by her husband, won custody of her 1-year-old daughter in 2019 after a Dakota County judge ruled the woman did not present a threat to the girl.

"That is just shocking to me," said Putnam-Hornstein, the researcher at the University of North Carolina. "Those are cases where [other states] bypass reunification efforts."

Rowan Stephens

In 2012, doctors raised alarms when Nicole Stephens brought her infant son Rowan to a clinic and X-rays revealed three fractures to his left leg. Rowan and his two siblings were quickly put into foster care when Stephens was unable to explain the injury and investigators matched bruises on his chest to her fingers.

Another concern: Stephens' first child, Aidan, died in his sleep while in bed with his mother in 2005.

Despite this history, Stearns County returned all three children to Stephens and closed the case after she demonstrated a "commitment to sobriety and safe parenting," records show. Rowan died a month later from a blow to his head. No one was ever charged in the death, which was classified as a homicide.

"It was determined that Rowan was physically abused and that the injuries resulting from the abuse led to his death," Stearns County said in the statement issued after declining interview requests. "It is not possible to determine who caused the life-ending injuries based on the evidence currently known."

A judge terminated Stephens' rights to her two surviving children in 2013 after county officials said Rowan's death showed his mother was unable to "provide minimally adequate parental care."

Stephens did not respond to calls or emails seeking comment.

Rich and Jean Stephens, who adopted Rowan's older brother and sister, said Stearns County should have let someone else raise Rowan.

"The policy is the problem," said Jean Stephens, whose husband adopted Nicole when she was a baby. "It's all about reunification, but what if it is not the right thing? What if it is wrong?"

In Dakota County, workers repeatedly recommended that a rape victim be returned to her parents in 2018 even though her adoptive mother blamed the girl for the abuse and forced her to watch sexually explicit videos made by her attacker. Court records show the girl, Simone Hunter, was afraid to go home and suffered post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of being raped over a six-year period by a relative, who was sentenced to more than 30 years in prison for the attacks.

"I think they should be ashamed," said Hunter, 22, who became so depressed she tried killing herself. "I can't tell you how many kids are like me, who have gone through the system and have been left for the world to tear apart."

Dakota County officials declined interview requests.

"Child protection workers want the best for children and families," Dakota Social Services Director Evan Henspeter said in a written response. "They work tirelessly to improve safety for children."

Kamari Gholston

Arneshia Cunigan temporarily lost custody of Kamari, her 4-month-old son, in November 2020 after she brought him to the hospital with an elbow injury she couldn't explain. While treating the infant, doctors discovered additional fractures to his ribs, arms and legs that were "highly suggestive" of abusive trauma, records show.

Hennepin County officials removed Kamari and his twin sister from her home in Brooklyn Center, but the children were returned to Cunigan three months later, after she enrolled in family therapy and "fully cooperated" with other recommendations.

Kamari was found dead two months later. He had been smothered.

Cunigan's 10-year-old son told police that his mom frequently choked and shook Kamari when he cried. The boy said Kamari's twin sister, Kamaya, escaped the same treatment because she was his mother's "favorite."

Cunigan pleaded guilty to second-degree manslaughter. She is serving a 41-month prison sentence. Cunigan also was charged with assault and malicious punishment of a child for the 2020 incident after Kamari died, but those charges were dismissed as part of the plea deal. She declined an interview request through a prison spokesperson.

Terrence Gholston, Kamari's father, blames the county for not giving him custody of both of his children in 2020, when Kamari was first injured. A judge gave him permanent custody of Kamaya in 2022.

"I don't think they valued my child's life," Gholston said. "I think it was just another case to them."

Hennepin County officials declined to comment on specific cases, but a spokesperson noted that the county has sharply reduced its rate of repeat abuse after missing the federal standard from 2017 to 2019.

"We've worked hard and are proud to have met the federal maltreatment recurrence performance measure since 2019," the county said in a written response to questions. "Still, we cannot acknowledge recent accomplishments without also acknowledging there are areas we're still working to improve."

Former staff writer Chris Serres contributed to this report.

About the project

In Harm's Way explores how Minnesota's child protection system fails to save some of the state's most vulnerable residents. Reporters began investigating in the wake of the 2022 death of Eli Hart, who was killed by his mother after being put back in her care.

To report on this topic, Star Tribune journalists spent more than a year examining thousands of documents, starting with more than 900 death certificates, dating back to 2011, that they cross-referenced with court records of child protection cases. Altogether, the reporters reviewed more than 1,000 child protection cases and dozens of related criminal cases statewide. They supplemented that information with data from state and federal reports on the child protection system.

To learn more about the individual cases, the Minnesota child protection system and best practices, reporters contacted hundreds of people, including families, social workers, guardians and state officials.

Credits

Reporting Jeffrey Meitrodt, Jessie Van Berkel, MaryJo Webster & Chris Serres

Photography Aaron Lavinsky

Photo editing Nicole Gutierrez, Emily Johnson & Katie Rausch

Digital design Dave Braunger

Graphics Yuqing Liu

Editing Katie Humphrey & Eric Wieffering

Copy editing Adelie Bergström & Catherine Preus

Digital engagement Sara Porter, Nancy Yang, Amanda Anderson & Jenni Pinkley

How to get help

People can find mental health information and resources for crisis care on NAMI Minnesota's website, namimn.org. If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, call the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline by dialing 988. You can also text HOME to 741741 to connect with a Crisis Text Line counselor.

If you or someone you know is in an abusive relationship, contact the Day One Hotline by calling 866-223-1111 or texting 612-399-9995.

If you suspect child abuse, report it to the county where the child lives. Contact information is at tinyurl.com/3bkwukax.

Contact us

The Star Tribune is continuing to report on Minnesota's child protection system. We would like to hear from families, social workers, judges, guardians ad litem and others who have been involved in child protection. Our reporters will not share your information without your permission. You can reach Jeffrey Meitrodt at 612-673-4132 or jeff.meitrodt@startribune.com. Jessie Van Berkel is at 651-925-5044 or jessie.vanberkel@startribune.com. If you'd like to submit a letter or commentary about this story or series, use this link.

Correction: A previous version of this story included a wrong date for when Arneshia Cunigan was charged with malicious punishment of her 4-month-old son. The charges were filed after the boy's death in 2021.