The news has roiled the Twin Cities' West African community: A program that allowed natives of the countries hardest hit by the 2014 Ebola epidemic to stay and work here is ending next spring.

In September, U.S. officials granted a final six-month reprieve to about 5,900 visitors from Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea here on Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and urged them to make departure plans before the program expires in May.

Community leaders had lobbied for the status and successfully pushed for extensions, arguing that the economies and health-care systems of these countries are still damaged even as infections have decreased.

Local West Africans said a majority of visitors will probably stick around and slip into the immigration shadows. They say they will keep lobbying, emboldened by a recent letter signed by Sen. Al Franken that urged President Obama to consider a much longer extension.

"Right now, these people are an asset," said Abdullah Kiatamba of the nonprofit African Immigrant Services. "They are not going to leave. They're going to stay in the shadows, become a burden and become a target."

In late September, national advocacy efforts bore limited fruit: Obama announced he would block deportations for another 18 months for longtime residents from Liberia.

Critics of TPS often cite multiple extensions given to natives of other countries — stretching more than a decade in some cases — to argue that the program is not really temporary.

Some voiced surprise that the government is winding the program down for the West African countries — even as they insist that should have happened sooner.

A haven from Ebola

Federal immigration officials have not released state-by-state numbers.

But local community leaders estimate between 500 and 1,000 people benefited in the Twin Cities — some who came to stay with relatives during the epidemic and others who had lived in the United States for years. More than 40,000 immigrants from the three countries live in the metro, one of the largest West African enclaves in the United States.

James Tuan's pregnant girlfriend came to Minnesota to visit a family member before the contagion hit their native Liberia.

As infections mounted, she decided to stay, and Tuan joined her after the birth of their son. Both are supporting children from previous relationships who still live in the capital, Monrovia, as well as members of their extended families. Tuan, who works at a north metro gas station, says relatives and friends back home complain about the stagnant economy and worry the deadly disease might strike again.

"Liberia is a bit better, but not too good," said Tuan, who lost a cousin and a close friend to the epidemic. "Everybody's still afraid of Ebola."

That's an argument that advocates for lengthier TPS for West Africans have echoed: Though the epidemic is over, the damage to economies already weakened by brutal civil wars in the 1990s and early 2000s lingers. Local leaders such as Karifa Jalloh say money sent home has offered a needed boost. He tells of one fellow Sierra Leonean who came on a visitor visa on the eve of the outbreak, lost her husband to it and now supports four children back home by juggling part-time jobs in a group home and manufacturing plant.

Critics of TPS have charged that the program offers open-ended reprieves to immigrants, including some who crossed the border illegally or overstayed visitor visas. They chastised the Obama administration for extending an application window for the three West African countries after the World Health Organization declared Liberia Ebola-free in the spring of 2015.

An end to reprieves

This past spring, the government offered what appeared to be a final six-month extension for the Ebola-affected countries. In the Twin Cities, a coalition of West African community leaders and the St. Paul-based nonprofit Immigrant Law Center pleaded with the state's congressional delegation to intervene.

"Folks are working here and contributing, and they are living in constant fear that tomorrow this program could go away," said one of the coalition's members, Abena Abraham, a college student whose family once benefited from TPS after fleeing Liberia's civil war.

In a letter to Obama this summer, Franken and 10 other U.S. senators cited the lingering effects of that war and a poverty rate of almost 65 percent in asking for at least a two-year extension. The letter also urged the administration to consider granting permanent status to end "perennial uncertainty about whether they will be able to remain members of the communities they have come to call home."

But in September the government said it had concluded that conditions do not justify a longer extension. It gave TPS recipients another six months to plan their departures or, if they qualify, apply for another immigration status.

"In my book, this is a victory because we were able to delay the expiration for another six months," said John Keller, executive director of the Immigrant Law Center. "But it's not as long a continuation as we wanted."

Local advocates are unsure why the administration decided to end the program quickly compared with some Central American nations. Nationally, pundits speculated that's because the number of West African recipients is fairly small, and that immigrant community does not have the political clout of U.S.-based Latinos.

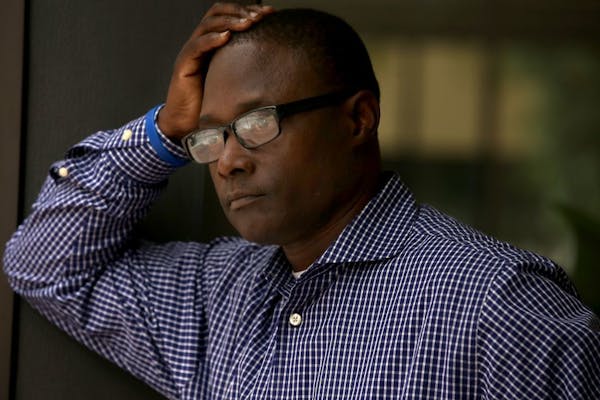

In the Twin Cities, Shelf Sheriff still struggles to come to terms with the announcement. He came to stay with a sister during the epidemic and, after TPS was granted, decided to stick around. Now, he feels his life is in Minnesota, where he works the night shift at a plant that manufactures reading lenses.

"I still hope there will be some kind of solution," he said.

Last week, Obama said there are "compelling foreign policy reasons" to extend for another 18 months a separate program that has blocked deportations to Liberia since an earlier TPS granted during civil war there expired in 2007. But that doesn't apply to more recent arrivals to the United States such as Sheriff.

Local advocates said they will press the next administration for a broader reprieve and a more permanent fix.

"Nobody's giving up," Keller said.

Mila Koumpilova • 612-673-4781

Charge: Driver going 77 mph ran red light, fatally hit man crossing St. Paul street and kept going

Minnesota Senate GOP files ethics complaint against Sen. Nicole Mitchell

High school archer focuses on target: another national championship