COVID-19 cases in Minnesota and across the country have dropped sharply this winter, but doctors and health officials say they aren't exactly sure of all the reasons why.

Adherence to social distancing, mask wearing and other health measures clearly helped slow the spread, and the rollout of vaccines may have started to make a difference, they say. Some speculate the virus might also have run up against cyclical factors as well as sizable pockets of immunity from prior infections, although there's not agreement among health officials on the magnitude of that protection.

Despite the decline, there's considerable uncertainty about whether it can be sustained, particularly as more contagious versions of the virus spread.

Federal officials warned on Friday the U.S. should not relax health restrictions since case declines might already have started to level off. In Minnesota, which was ahead of most states in reporting a winter surge, state officials last week said infection rates are now pushing higher in some rural counties.

"We're seeing some increases in what is coming. … We are by no means out of the woods yet," said Kris Ehresmann, the director for infectious diseases at the Minnesota Department of Health.

Of the cause for the drop in cases this winter, she added: "There are a lot of things that we don't know."

On Saturday, the state Health Department reported 826 new coronavirus cases and 13 more deaths linked to COVID-19. The seven-day rolling average for net case increases stood at about 805 per day — down slightly from Friday's reading, but up from last Saturday's comparable figure of roughly 767 new cases per day, according to the Star Tribune's coronavirus tracker.

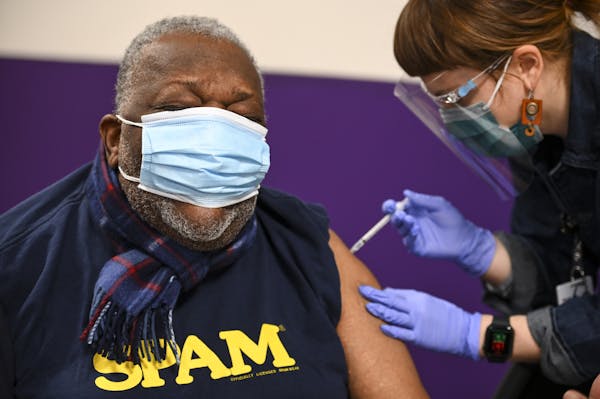

The statewide tally for people who have received at least one vaccine dose increased to 836,735 people so far. That's about 15% of the state's population, according to Star Tribune estimates.

Dramatic case declines this winter are a humbling reminder of the uncertainty over exactly what drives the virus, said Dr. Paul Sax, an infectious disease specialist at Harvard Medical School.

Whereas the U.S. averaged about 250,000 cases per day in January, that dropped to less than 70,000 this month. The trend spans countries around the world, Sax wrote this month in a blog post for the New England Journal of Medicine, and includes places such as the United Kingdom and South Africa, where virus variants have widely circulated.

The pattern resembles seasonal flu with cases rising to a peak in winter before turning. Yet seasonal changes can't fully explain the drop, he said. Some countries in the southern hemisphere, where it is now summer, have seen a similar case declines.

It could be that immunity from previous infections is broader than scientists can document, Sax said. A related theory is that the virus already has infected a large number of people with the highest exposure risks, including those who must work outside their homes, live in crowded settings or simply opt not to follow health guidance.

But, Sax concluded in an interview last week: "I can't really give any single explanation."

As cases surged in late fall and early winter, people did a better job of wearing masks, social distancing and following public health guidelines to get tested and stay isolated when needed, doctors say.

At the same time, the decline in cases has some health officials wondering whether growing immunity from past infection and vaccination has made a big difference.

"It doesn't mean on the population level, among all the adults in the U.S., that there's herd immunity," said Dr. David Boulware, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Minnesota Medical School. "But as the number of susceptible people decreases due to past infection and vaccination, the chance for the virus to spread decreases."

That shouldn't provide a false sense of security for people who have been working from home and following health guidelines, said Dr. Eric Toner, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. People who have "hunkered down are all quite susceptible until we have been vaccinated," he said.

Overall, Toner thinks cases will continue to decline across the country, albeit with "some spotty spikes here and there." Even with the leveling off in cases described by federal officials last week, he doesn't expect another big surge.

Citing the effectiveness of vaccines, Sax also expects a continued decline. Warmer weather in the northern hemisphere also should help, he said, since spring and summer allow for more gatherings outdoors.

But Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, fears trouble ahead.

Too often during the pandemic, speculation about pockets of immunity in certain subgroups has been followed by outbreaks in those very populations, he said. What's more, he added, the share of the population with previous infection is just not big enough yet, studies show.

"We've still got 60% of our population that is vulnerable to this virus after a year," Osterholm said. "And look what we've been through with clinical disease and vaccination just to get to 40% protection."

Osterholm has raised alarms for weeks over the spread of the B.1.1.7 variant, a version of the virus that was first identified in the United Kingdom and is thought to be more contagious and virulent. Sequencing data last week show the variant is quickly spreading in California and Florida, Osterholm said, adding that a new study calls for the U.S. to take "immediate and decisive action to minimize COVID-19 morbidity and mortality."

"How big it is, we're not completely clear yet," Osterholm said of a surge he believes is coming. "We just have so few vaccinated relative to the population, we still could have a major surge in cases occur because of this particular strain."

Boulware said he worries that spring break travel might trigger more cases. Like Osterholm, he thinks the U.S. should strongly consider a delay in administering second doses of vaccines so more people can quickly receive first shots, giving them at least some protection.

That's what happened in the United Kingdom, and the experience suggests the U.S. could benefit, said Dr. Gregory Poland, a vaccine immunology specialist at Mayo Clinic. Still, Poland said, doctors can't fully explain the case decline because potential factors range from travel and human behavior to viral changes and vapor pressure.

One alarming consequence of the lower case numbers, Poland said, is that it's leading many politicians, business leaders and individuals to call for lifting restrictions just as the variants are spreading.

"It is a race between vaccine and virus," he said. "Because we don't have enough vaccine out yet, and because we don't have a policy of [giving] as many people as we can one dose as quickly as possible, I believe we will see a fourth wave — a resurgence."

Christopher Snowbeck • 612-673-7744

Medcalf: Join us for our book club talk with author who was wrongly convicted and freed after being on death row

Officials reveal reason Robbinsdale shelter-in-place alert mistakenly was sent countywide

DFL state senator charged with first-degree burglary in break-in at stepmother's home