Why didn't Minneapolis and St. Paul ever merge?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

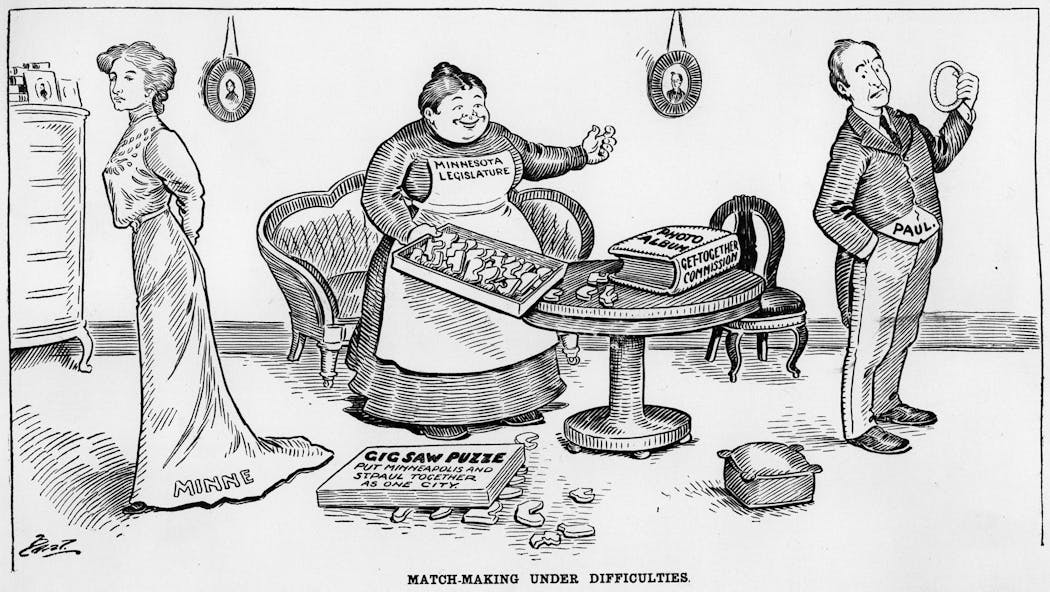

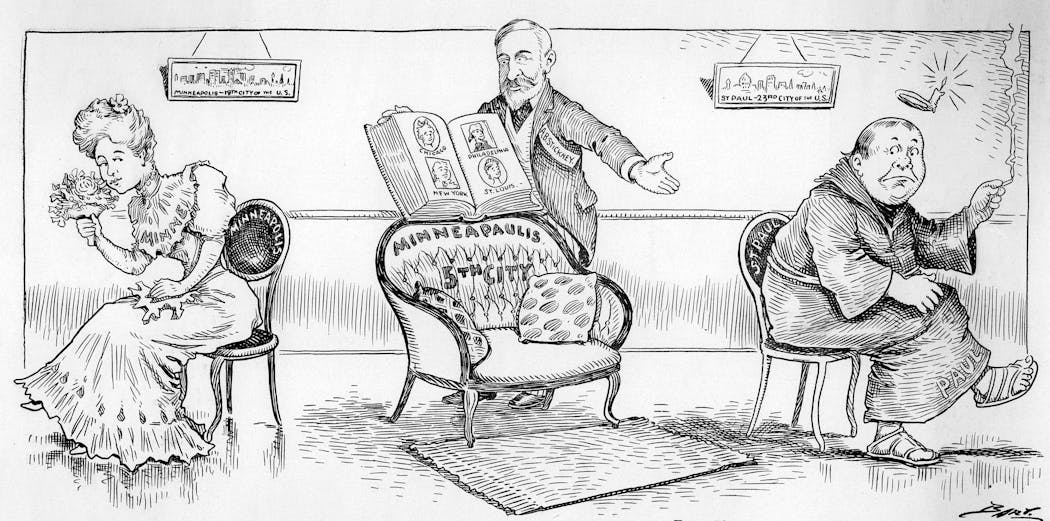

Minneapolis and St. Paul would rank among the top 20 largest cities in the country today had they chosen to merge over a century ago — creating Paulopolis, Minneapaulis or one of the other names proposed for the united city.

Each of the twins instead is nipping at the heels of cities like Oakland and Newark, which are far smaller than the Twin Cities' peer regional centers like Seattle, Denver and Boston.

That's one reason why Scott Berger, a patent lawyer who grew up in Edina and lives in St. Paul, turned to Curious Minnesota — the Star Tribune's reader-powered reporting project. He wanted to know why Minneapolis and St. Paul remained separate, and whether they ever considered joining forces.

"Minneapolis and St. Paul are underrepresented because of population," Berger said. "It just feels to me that it would be more fair to the cities to share the load, the benefits, the tax base, and unify our identities. They have more similarities than differences."

In fact, movers and shakers in both cities engaged in serious talk of a merger as far back as the 1880s. Many thought it was only a matter of time.

"That Minneapolis and St. Paul are to be united is simply manifest destiny," the Minneapolis Tribune thundered in 1891, going on to say that the cities already had "become practically one city, so far as continuous streets and settlement are concerned."

It didn't happen because of a simmering social and business rivalry between the two cities, each of which had developed distinct cultures and were propelled by very different economic engines. Those contrasts, fueled by jealousies and suspicions that erupted into urban warfare over the 1890 Census, simply couldn't be bridged.

"About the time when people in St. Paul were saying a merger wouldn't be so bad, Minneapolitans were turning up their noses," said Mary Lethert Wingerd, a retired labor historian and professor who wrote "Claiming the City," the seminal book on St. Paul's origins.

Merger momentum

When local newspapers referred to the Twin Cities in the 1860s, they meant Minneapolis and St. Anthony. The two settlements across the falls had all the signs of budding civilization: sturdy houses, churches, schools, museums.

Charles Hoag, one of Minneapolis' first educators (and credited with coming up with the city's name), told the Old Settlers' Association in 1869 that their children would one day see Minneapolis and St. Anthony unite with the downriver community of St. Paul "under one municipal government."

Minneapolis annexed financially-burdened St. Anthony a few years later, and by 1880 was a city of nearly 47,000 on its way to becoming the flour milling capital of the world — just as St. Paul's fortunes were sliding and railroads were replacing river commerce.

"Minneapolis really from the get-go was controlled by New Englanders," Wingerd said. "St. Paul was a conglomeration of all kinds of different people. They had very little in common."

Nevertheless, land speculation in St. Paul's undeveloped Midway district, about equidistant between the two downtowns, helped to fuel merger talk. The St. Paul Globe predicted a new state capitol building would rise there, and Archbishop John Ireland bought up property for his envisioned cathedral in "the very heart of the coming great city" that he called "Paulopolis," according to Ireland biographer Marvin O'Connell.

But whatever momentum was building toward a merger came to an abrupt end in 1890, when Minneapolis and St. Paul engaged in a highly publicized brawl over which city had the most residents. Both cities connived to pad their numbers and win the upper hand in what became known as the Census War.

A St. Paul spy reported to his superiors that Minneapolis enumerators were making up lists of families, leading to their arrests by a federal marshal. When Minneapolis officials went to St. Paul with a warrant to recover six bags of evidence, St. Paul police officers drew their revolvers and showed them the door.

An investigation by federal officials uncovered a conspiracy to inflate population figures in Minneapolis and lesser incidents of fraud in St. Paul. Minneapolis lost the battle, with about 18,200 phony names expunged compared with 9,400 in St. Paul. But the Mill City won the war: The final count put it at nearly 165,000 residents, compared to 133,000 in St. Paul.

The census dust-up "put what appears to be a final stopper upon the movement for civic union," a St. Paul historian wrote in 1906.

'Better off without St. Paul'

Excited anticipation for a merger ratcheted up again in 1891, when a widely distributed pamphlet forecast the eventual union of the two cities as one breathtaking "Federal City," population 900,000, with mayors alternating from both sides of the river.

The St. Paul Chamber of Commerce swallowed hard and decided to take the plunge. That summer, it voted to form a committee to lay the groundwork for a merger and invited the Minneapolis Board of Trade to do the same.

A month later, the St. Paul chamber finally got an answer from the Minneapolis board: Not interested. The only reason St. Paul wanted to merge was to boost land values in the Midway district, the Mill City tycoons said.

"We don't want union with St. Paul; we don't want to even consider the matter," sputtered Minneapolis board member J.T. Wyman. "We are stronger and better off without St. Paul."

"St. Paul reluctantly realizes that it isn't going to be the center of the Northwest, and that's going to be Minneapolis, those people across the river — those arrogant upstarts," said Twin Cities historian Iric Nathanson. "So St. Paul says we have to pull together as a community if we're going to get out from under their shadow."

The news of "Poor Paul Jilted" flashed across the nation. "There will be no more gibberish about Minnipaul or Paulopolis," asserted one Ohio newspaper.

The Legislature's decision in 1893 to keep the State Capitol in downtown St. Paul put an end to the Midway land rush, and Archbishop Ireland decided to build his cathedral on Summit Avenue instead.

Continued calls for a coupling

Still, the flame of merger continued to flicker. The Minneapolis Tribune polled newspaper editors across the country in 1895 about a potential merger, and many said it should happen.

"In my recent visit to your city, I rode between the two cities on the electric line and noted the wonderful filling up with buildings of what a few years ago was farm lands," wrote the editor of the Chicago Times-Herald. "Every new improvement brings you closer together."

Not everyone was convinced. "Except for the bitterness displayed in it at times, the rivalry between [the cities] is healthy," wrote the manager of the Tacoma Ledger.

The president of the Chicago Great Western Railroad, A.B. Stickney, urged the cities to unite in a speech to the St. Paul Builders Exchange in 1906. They would together make "a world commercial power," he said, pointing to New York and London as examples of cities that had grown in status through consolidation.

"Do the people of St. Paul and Minneapolis understand," Stickney said, "what it would mean ... to be recognized as the sixth [most populous] city in America?"

A bill passed the House in 1909 creating a legislative committee to draw up a merger plan, though newspaper reports suggest that many of those who supported it didn't take it seriously. In 1943, St. Paul legislator John Drexler introduced a bill to merge the two cities into "Twin City," once local government officials and voters agreed. It went nowhere.

Nathanson, who grew up in Minneapolis and has worked in government on the local and federal levels, said he wasn't sure that combining Minneapolis and St. Paul into one big city would have meant all that much in the end.

"We'd still be in flyover country," he said. "We'd still have 30-below winters. I think frankly it's much more interesting to have the two cities that are very different. And we long-timers need to educate the newcomers that they ... should get to appreciate those differences."

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Why do tiny cities like Lauderdale, Landfall, Lilydale, & Falcon Heights exist?

Is it true that Minneapolis has a park every six blocks?

Why is 'southeast' Minneapolis actually northeast of downtown?

Where did streetcars once travel in the Twin Cities suburbs?

Who dug the sandstone caves along St. Paul's riverfront?

West, North, South, Park: Why are there so many suburbs named St. Paul?