How did pro baseball get its start in Minnesota?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

A well-known sign at Target Field portrays two baseball players representing the Twin Cities, Minnie and Paul, shaking hands over the Mississippi River. It reflects a relatively recent trait of professional baseball in Minnesota: unity.

Fierce competition between cities, by comparison, spurred the creation of the state's first professional teams that paid players in the 1870s.

Jimmy Lonetti wanted to know how professional baseball started in Minnesota and which team paid its players first. Lonetti and his son Dom repair baseball gloves at their Minneapolis business, D&J Glove Repair. He sought answers from Curious Minnesota — the Star Tribune's reporting project powered by reader questions.

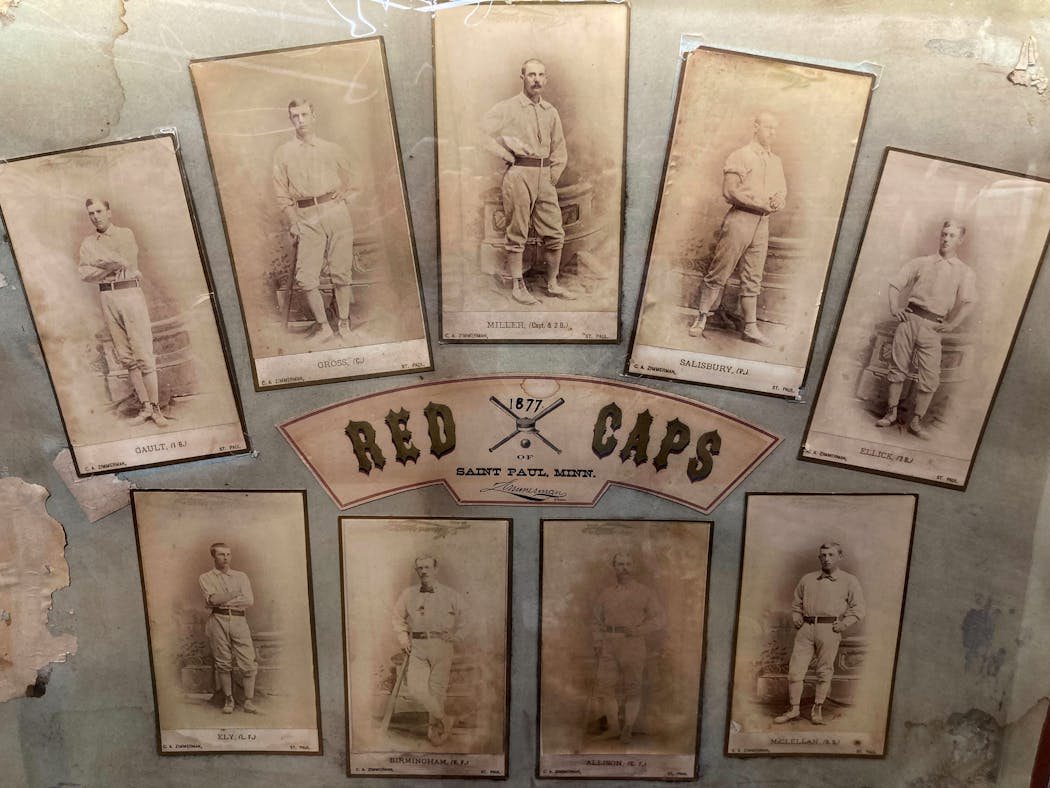

Growing competitiveness, race-based exclusion and cheating scandals marked baseball's earliest days in Minnesota, culminating in the arrival of professional teams in 1877. Befitting of the Twin Cities, pro ball came in a pair: the rival St. Paul Red Caps and Minneapolis Brown Stockings.

Baseball's popularity in the United States grew from its inception in the late 1700s into organized teams in the 1830s and '40s. National conventions held in the late 1850s formalized early rules of the sport.

In 1857, a team based in a town outside Hastings adopted the rules of the first baseball convention in New York. In doing so, the Nininger Base Ball Club became the first official organized amateur team in the state, according to modern historians.

The early years

Intercity baseball started in Minnesota as a friendly enterprise in 1865, fueled by the return of soldiers from the Civil War. Teams would often dine together before or after games with songs and speeches. But as fans grew more committed to their local teams in the late 1860s, winning became more important than camaraderie.

"Professionalism and money are going to creep into everything," said Stew Thornley, author of "Baseball in Minnesota: The Definitive History." "There gets to be so much pride and competitiveness of getting beat by another city."

Teams typically constructed their makeshift home fields in common areas next to local churches or other noteworthy buildings — like a bell tower or newspaper offices. Games were well attended, with women making up a significant portion of the crowd and bets exchanging hands, according to the St. Paul Pioneer in 1867.

Thornley points to 1869's state championship series between the St. Paul Saxons and the Gopher State Club of Rochester — both still amateur clubs — as emblematic of the new hostility driving the desire for professionals.

In the first game, players stormed the field over the Saxons' use of an extra fielder behind the catcher. In the second, the Saxons inexplicably walked off the field and kept the trophy with them, according to the 1938 book "The Rise of Baseball in Minnesota."

The first few professional players started popping up in Minnesota later that year on semi-pro teams — a mix of paid and unpaid players. Teams typically imported the professional players from out of state.

"I just see the desire of the fanatic," Thornley said. "People wrap up their own self-esteem and self-image in how their college does or how their favorite team does. And we know how nutty that gets with people brawling over it."

Paying for better players could give a city's team the advantage it needed to win the state championship, Thornley added.

Racial tensions

Individual paid players became increasingly common by the mid-1870s, but not all of them were welcome. The arrival of W.W. Fisher, a Black pitcher and infielder signed by the Winona Clippers in 1875, sparked debate about racism and professionalism in the sport.

The St. Paul Red Caps banned Fisher from competing in a tournament they were hosting at the State Fair in September. Standing up for their local player, the Winona Daily Republican newspaper noted that Fisher was an experienced member of the team who "is not only an expert player, but a gentleman in his department."

"The managers of the State Fair have shown themselves weak in not taking the matter at once into their own hands and saying that the tournament was open to all clubs whether they had any colored players or not," the newspaper wrote.

The Red Caps scrambled to withdraw their objection, saying their problem with Fisher was not his race but his professional status. Winona re-entered and won the tournament, with Fisher scoring a team-high 11 runs.

Fisher had faced discrimination earlier in the season. Before a game against the Northfield Silver Stars, the Stars pinned racist ornaments on their badges and marched around town in protest of Fisher, according to the Winona Daily Republican.

"There were a lot of places where nobody was hiding the fact that their treatment of Fisher was because of his skin color," Thornley said. "So the racism was certainly heavy and out there, but sometimes people would still use professionalism as a smokescreen."

Professionalism takes hold

The pushback against professional players gradually waned, however.

The Minneapolis Blue Stockings, a new club founded in 1876, quickly pursued professional talent. A traveling team from Detroit shut them out with the help of what historians believe were some of the first curveballs thrown in the state. By the next week, the Detroit pitcher and his catcher had signed deals with Minneapolis, according to Minnesota baseball historian Rich Arpi.

The appetite for professional baseball accelerated that October when the National League's juggernaut Chicago White Stockings arrived in Minnesota for a round of exhibition games. Fans flooded in to watch their first game in St. Paul — despite a steep 50-cent ticket price. The team stuck around St. Paul to play another game due to fan enthusiasm.

Chicago's tour signaled pro baseball's arrival the next year. Arpi said the move toward professional teams occurred over several years starting in 1875 as competition heated up.

"By 1877, a good number of the clubs were openly professional," Arpi said.

A new "loose confederation of teams" called the League Alliance, which both St. Paul and Minneapolis joined, characterized the 1877 season. St. Paul, wearing all white except for its red hats, kept the Red Caps name. Minneapolis changed its socks from blue to brown, calling themselves the Brown Stockings.

Arpi believes the Red Caps were fully professional the entire 1877 season behind a core group of players imported from states like Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island. The Brown Stockings reached that status by the end of the year, he said.

The League Alliance folded after a year and the clubs sustained major financial losses that "soured the state's baseball entrepreneurs on the sport as a profitable enterprise," according to Arpi.

Minnesota's professional baseball was resurrected in the mid-1880s with the formation of the Minneapolis Millers and St. Paul Apostles. The Millers and a subsequent St. Paul team, the Saints, would become the region's primary professional baseball teams until the arrival of the Minnesota Twins in the 1960s.

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Why are all of Minnesota's pro teams named after the state, not a city?

Who are all the people on sidelines during Vikings games?

Why is the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame located in tiny Eveleth, Minnesota?

Playing favorites: What's the story behind Twins' jersey picks?

Why isn't it a crime to punch someone in the face in pro hockey?

What is the oldest building in Minnesota?