Why a slice of I-94 west of the Twin Cities is a 'candyland for researchers'

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

A divided section of Interstate 94 west of the Twin Cities looks — at first glance — like any old construction detour that pepper state highways. But this is no ordinary fork in the road.

Minnesotans zipping to and from work, home or the family cabin on this 3.5-mile stretch of freeway are unknowingly helping engineers in Minnesota and around the country design better roads. The westbound lanes between Albertville and Monticello are part of MnROAD, one of the country's leading pavement research facilities run by the Minnesota Department of Transportation.

An anonymous reader sought more information about the purpose of this test road from Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's community reporting project fueled by reader questions.

Researchers at MnROAD primarily study how different pavement materials and designs hold up in real-world traffic conditions amid Minnesota's harsh winter climate. They conduct as many as 50 experiments at a time on the westbound lanes, aided by data from underground sensors.

Engineers as far away as Iceland rely on the findings, since variables like traffic, temperature, moisture and the passage of time are difficult to recreate in lab environments.

"We can develop new paving materials, pavement designs, and better ways of managing our roadways and have real world data from MnROAD to back our results," explained MnDOT engineer Ben Worel, who oversees operations at the facility.

There are actually three sections of test road. In addition to the westbound lanes, a MnDOT truck loaded with weights makes loops on a self-contained "low-volume" road to the side of the freeway. MnDOT periodically closes one of the westbound lanes to make changes to the roadway.

Researchers inspect the roadway for visible changes, such as ruts, faults, cracking. But they also analyze pavement temperature, moisture, and the strain of passing vehicles using the underground sensors, which are linked by fiber optics directly into MnROAD's systems.

The data collected from the experiments enables MnROAD and its partners to make design or material recommendations based on small investments in the test sections. That can shape policies affecting the way Minnesota approaches infrastructure around the state.

The ultimate goal, Worel said, is innovation in the way roads are built and finding a balance between long-term durability and fiscal responsibility.

"Transportation, bridges, infrastructure — all these things we take for granted take a lot of money to keep running at our level of quality," Worel said. "Much of our roadways were originally built in the 60s and 70s and they are getting old and need to be maintained. But we also are adding new roads each year."

'Candyland for researchers'

One recent study conducted at MnROAD might help answer a question every driver has probably asked themselves: Why does road construction take so long?

MnROAD and its partners are looking at how long concrete pavement needs to cure before traffic is allowed back on, and what long-term damage occurs if cars drive on it too soon. That research, which is still ongoing, could one day shorten the delay experienced by drivers.

"MnROAD is kind of candyland for researchers," Worel said. "Researchers from around the world have all the things they need to make new models, develop new materials, test designs and processes in a safe environment."

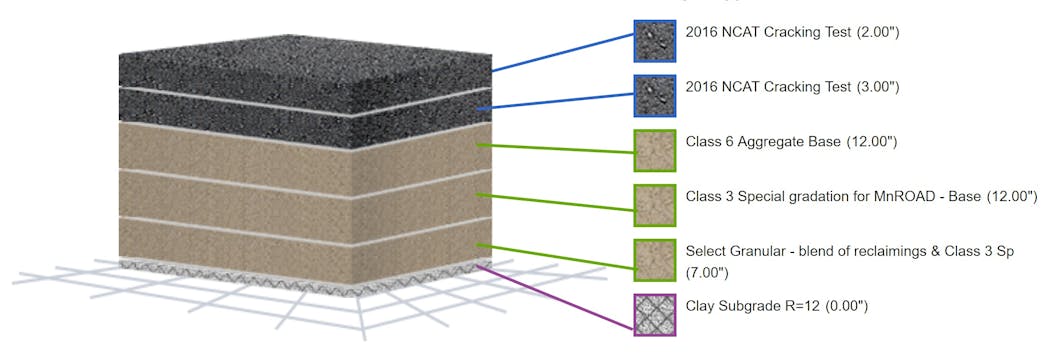

The test road is divided into segments that each contain a unique sandwich of gravel, asphalt, concrete or other materials — which can be viewed online.

The price tag to build MnROAD in the early 1990s is the equivalent of about $80 million today when adjusted for inflation. MnROAD estimates their studies have saved the state millions of dollars each year by increasing pavement longevity and reducing maintenance costs.

MnROAD is one of several facilities of its kind in the nation. But its research is more comprehensive than most of its peers.

The state's weather alternates between extreme lows and highs throughout the year, which allows experiments for many types of climates to be run on the test roads. Most sites test only asphalt, while MnROAD tests both concrete and asphalt. Concrete testing is key for smaller, non-interstate roads like city and county streets. Nowhere else can both pavements be evaluated for so many factors interacting under live traffic and extreme weather.

A lot of the current research is focused on how to build and maintain roads sustainably.

"Now, we're doing a lot of projects related to road designs using recycled materials," said Glenn Engstrom, a MnDOT employee who is director of the National Road Research Alliance (NRRA), an organization comprised of governmental agencies, academics and private companies that helps fund research at MnROAD. "We want to reduce our effect on the environment. And a lot of that is in how we use and reuse materials as we construct roads."

The research can also help transportation departments work more efficiently, Engstrom said. Potholes, for example, are relatively simple and inexpensive to repair — but those costs quickly add up. At MnROAD, researchers are exploring ideas to stop potholes from happening at all.

Worel noted the process of building roads has grown a lot more complex over the years.

"It's not as simple as it was and you have to do your homework and research to understand roadways if you want to effectively make positive change for the future," he said.

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Why does I-35E through St. Paul have a 45-mph speed limit?

Should you really let your car run on cold mornings before driving it?

Is Minnesota's power grid ready for widespread electric cars?

Are roundabouts really safer than traditional intersections?

Why are motorcycles allowed to be so much louder than cars & truck?

Why was I-94 built through St. Paul's Rondo neighborhood?