Holly Vilione wasn't quite sure what to expect when she walked into room 768 of the intensive care unit on that December morning.

Her 60-year-old patient had been lying in bed and hooked up to a ventilator for more than three weeks while trying to survive the worst of COVID-19. Now, with his lungs growing stronger, it was time to see if he could sit up on his own.

Donning a mask and gloves, Vilione wrapped a yellow and gray gown over her royal blue scrubs and began working with a physical therapist and his assistant to move her patient to the edge of his bed. They lifted his torso and swung his feet to the floor. Minutes later, all three let go.

The man lurched forward, then caught himself — supporting his weight for the first time in weeks. As Vilione and colleagues grabbed hold again to steady him, they burst out with a cheer that broke the somber hush in the hospital hall.

"We get excited for very small things," Vilione said. "But this is a huge thing in his life."

Triumph and sorrow play out daily in the intensive care unit at North Memorial Health Hospital in Robbinsdale, where Vilione pulls shifts treating some of the most challenging of COVID-19 cases.

Working for the past 11 months in a cluster of rooms known as "South Seven," the 37-year-old critical-care nurse has watched as patients gasped for air and struggled to breathe. She's looked on with dread as the sickest, fighting to survive, were hooked up to a ventilator. She's been there, too, when patients, ravaged by the virus, declined use of the machine, saying they were too weary to go on.

For Vilione, a mother of three from Maple Grove, it's heartbreaking duty that in recent months has become sadly personal, too.

Last August, after Vilione and relatives gathered at the family cabin in Wisconsin for a weekend celebration, she and four others became sick with COVID-19. All recovered except for Vilione's mother-in-law, Carol, who died after spending her final weeks linked to a ventilator.

Vilione, who assured her mother-in-law in the days before the gathering that all would be safe, is haunted by questions of guilt and responsibility. Not a day goes by, she says, when she doesn't regret that decision or wonder if she was the one who spread the virus to others.

Yet the pain of that loss has deepened her commitment to the difficult work in South Seven, where she draws on her skills, sense of compassion and the support of colleagues to wage what she calls a "personal vendetta" against the deadly pandemic.

The number of COVID-19 deaths and new cases has dropped significantly this winter in Minnesota, relieving pressure on hospitals. Yet caregivers remain wary as more infectious forms of the virus surface amid impatience that vaccines aren't reaching people faster.

"You feel like you're at war. You feel like we're doing some good for people," Vilione said recently after finishing a shift. "I still want to go to work every day, as sad as that work is."

Providing critical care has long been stressful, yet there's concern in the profession that the prolonged burden from COVID-19 could ultimately lead to burnout and departures, as doctors and nurses repeatedly confront the most devastating consequences of the disease.

Roughly 1 in 4 COVID-19 patients admitted to ICUs don't survive, according to a national registry from Mayo Clinic and the Society of Critical Care Medicine. The registry also shows that the most severely ill are staying for weeks in units, well beyond ICU norms.

At North Memorial, the lengths of stay with some virus patients are "just something we haven't seen before," says Dr. Kristen Hasson, a critical care specialist. Some have stayed more than 50 days, a duration that Hasson calls "astounding."

Workers, meanwhile, worry about exposure and the risks to their own health. More than 35,000 health care workers in Minnesota have been infected by the virus that causes COVID-19, although state data suggest most hospital worker cases from high-risk exposures have happened away from work.

Front-line clinicians who have provided nearly yearlong COVID care feel "conflicted," said Dr. Lewis Kaplan, president of the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

"You feel drawn to the profession. You feel compelled to render care for patients, to help people get better," Kaplan said. "And at the same time, you wonder, especially if you feel emotionally or physically exhausted: How do I get out? And then you feel guilty about perhaps extracting yourself from continuing to be at the bedside — you have a unique skill set.

"It's a very unmoored time in critical care."

Vilione, who always wanted to be a nurse, admits it's been daunting.

Growing up in Argyle, a town of 640 people in far northwestern Minnesota, Vilione followed her sister's example in high school by taking a job working with Alzheimer's patients in the town's nursing home.

Today, both sisters work as critical care nurses at North Memorial.

Vilione switched to the ICU about five years ago, drawn by the sense of urgency in critical care, where she felt her knowledge and skills could help patients whose lives were hanging in the balance. She also sought the close connection nurses often develop with relatives of patients, even when the outcomes aren't good.

"There's something very important," she says, "about being with someone on their last days."

With COVID-19, however, death has become a much bigger part of the work.

More Minnesotans died in hospitals from COVID-19 in December than during any month since the pandemic surfaced in the state nearly a year ago. North Memorial wasn't spared by the surge, and state records show it was one of several hospitals in Minnesota reporting an average of more than one death every day.

Moments after watching her patient sit up on that December morning, Vilione pointed to a nearby room in South Seven where family members were allowed to visit a loved one as she neared death. The woman's husband of 35 years tenderly ran his fingers up and down her arm.

Such scenes sometimes eclipse the happy memories of patients who recover and make it out of the unit.

Vilione speaks with sadness of the elderly COVID-19 patient who rejected going on a ventilator, even though the decision meant he wouldn't survive. He was too tired to continue, he told Vilione, and was ready to meet God. When his sons came to say goodbye, Vilione stood by their side, her face wet with tears.

"It was the most heart-wrenching day," she says.

Vilione's green eyes often reflect the emotions of the ICU. They also command attention as she talks with colleagues in a unit that's quieter than it once was, with all rooms now closed off because of the virus.

Petite with shoulder-length hair, Vilione is both direct and disarming, speaking with confidence while drawing people in.

On this December morning, the hospital is buzzing with excitement as North Memorial receives its first vaccine shipment. Yet a colleague fears that with millions in Minnesota still needing vaccine doses, life won't soon return to normal.

"I hope there's a day," Vilione says, "when we can come to work without a mask on."

Before COVID-19 and mandated wearing of masks, Vilione spoke with families face to face as they visited loved ones. Now, she is forced to forge a bond through regular phone calls, where she provides updates on patients. Nurses try to paint a picture that's accurate, Vilione says, but the impulse to be kind and reassuring can sometimes run up against painful facts when a patient's condition doesn't improve.

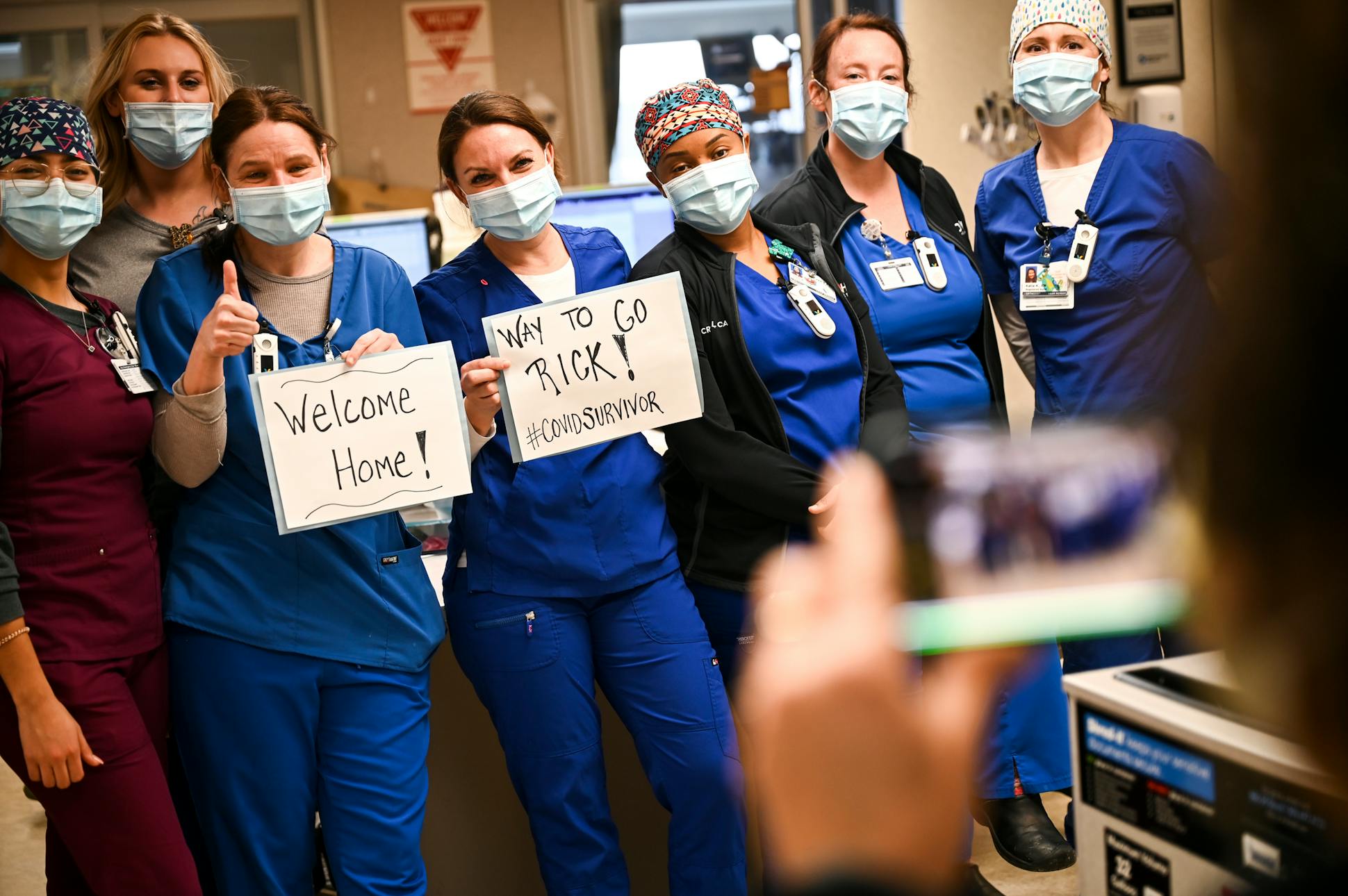

On this day, at least, Vilione can deliver good news to Deb Ulrich, whose husband, Rick, sat up on his own for the first time since coming off a ventilator.

Holding a phone in the middle of the ICU, she quietly describes Rick's progress, stressing the positive in a calm, steady voice. Not only did he hold himself up for a moment, she says, he tolerated sitting on the edge of the bed for more than five minutes.

By week's end, she adds, doctors expect he will be discharged to a long-term rehabilitation center.

When mentioning the transition, Vilione senses hesitation on the other end of the line. It's scary to think about a change, she said, but moving on is a crucial step toward getting home.

"I know it's hard to stay positive, but it's the only thing that's going to keep you going," Vilione tells Deb Ulrich. "He's had a lot of complications and he's made it through everything."

Vilione knows from personal experience that loved ones hang on every word.

Only five months ago, she and her husband, Chris, were on the other end of the phone conversations, desperately waiting for encouraging words from hospital caregivers on the status of her mother-in-law, who was on a ventilator and fighting for her life.

Early last summer, the Vilione family had considered options for their annual gathering at a cabin near Wisconsin Dells. Despite the complications caused by a global pandemic, it was an important tradition — and one Carol Vilione, who lived outside Milwaukee, desperately wanted to continue.

Holly, Chris and their three young children all would be there, along with Chris' older brother, Nick, and his family, who live near Chicago.

Yet anxious as Carol was to see her children and grandchildren, she was leery, too.

Never a smoker, she had been diagnosed two years earlier with lung cancer. Doctors caught it early and had managed it into remission, but Carol and her husband, Don, were extremely cautious about socializing amid the pandemic.

The boys were sympathetic and supportive, but also figured the families could meet safely at Nick's cabin, away from whatever crowds they might find at the Dells, a popular vacation spot. With her sons encouraging her, Carol turned to Holly for guidance.

"What do you think, Holly? Do you think we should go?" Holly recalled her mother-in-law asking.

"And, of course," Holly remembered, "I said, 'Yes, we really want to see you.' "

At the time, the daily coronavirus case counts were relatively low. The number of virus deaths had dropped significantly from the spring. At North Memorial, only two COVID-19 patients were being treated in South Seven. What's more, health care workers like Holly had experience using protective equipment to avoid infections.

"I think it's safe," Holly told Carol.

Within days of the weekend gathering, however, Holly, Carol and three other adults got sick with the virus. Carol suffered the worst case. Once admitted to a hospital near Milwaukee, she soon called her family in a panic, saying doctors were putting her on a ventilator.

Holly could hear the terror in her mother-in-law's voice and tried to reassure her.

"My last words to her were: 'This is not your time. You're not going to die from this. I'm going to take care of you.' "

Over the next four weeks, as Carol battled the virus, the family became dependent on daily phone updates from nurses and doctors. After each call, they'd dissect the conversations, reviewing not only the words they heard but also the tone from caregivers — desperate to find snippets of hope.

At one point, doctors thought they'd be able to wean Carol from the machine. But when her case took a sudden and frightful turn, caregivers, thinking death was near, let Don sit at her bedside.

Carol rallied that day. Holly wonders now whether Don's presence might have helped somehow. Still, the ultimate prognosis would get no better over the next few weeks. Carol was just too sick. She died Sept. 24.

Looking back, Chris Vilione says no one can know for sure how the virus spread to the cabin that weekend.

"Any one of us could sit here and think, 'Oh, this is on me,' " he said. "But that's not going to help us. And my mom wouldn't want that. When I say family's everything to us, I mean she wouldn't want this — what happened to her — to destroy everything she worked for her whole life, which is such a tight family."

Despite strictly adhering to infection control protocols, Holly still fears she may somehow have been exposed while working in South Seven — or even outside work — putting the others at the cabin at risk. Her remorse centers on the choice to gather that weekend in the first place.

"She just really wanted to see us and the grandkids, so they decided to come," Holly said, with tears in her eyes. "And not a day goes by when I don't regret that decision."

As Carol fought to stay alive, Holly suffered from fatigue and a horrendous cough. Her recovery from COVID-19 was probably delayed, she said, by the stress of watching Carol's health deteriorate while also trying to help her family interpret messages from caregivers.

In the weeks after Carol's death, Holly was reluctant to return to work but felt compelled to help her unit, since COVID cases were beginning to surge in Minnesota. She knew the sight of ventilator patients would remind her of what Carol had suffered, but the good memories of her mother-in-law also helped to motivate her.

Since returning to work, she has tried her best to bridge the gap between patients and families, making sure no question about a loved one's health goes unanswered. She'll figure out the best time to reach a family member for daily calls and is careful not to miss the window.

With face-to-face visits between patients and their loved ones still risky as the virus continues to spread, she is quick to suggest video visits and gently encourages them even when families are hesitant.

Still, screens are no substitute for bedside visits, and Holly will plead with supervisors to allow family members into South Seven as soon as possible. Patients need to hear a comforting voice. And she knows from her father-in-law's experience that being in the ICU, while painful, helps families cope when hope is gone.

Holly seldom tells the story of her personal loss to patients or their families, preferring to keep the focus on their struggles. But sitting in South Seven on a December afternoon, she teared up while describing all that's happened.

She threaded a tissue beneath a plastic shield to dab at her eyes as a co-worker offered a reassuring hug.

"I'm struggling. They know it," Holly says.

All caregivers are shedding more tears these days, she says, adding with a slight laugh, "Maybe me just a little bit more."

It's dinnertime at the Vilione house, and Holly is tending to pasta on the stove while holding 2-year-old Nora on her hip. In a few minutes, her middle child, Reed, comes up from the basement, bouncing exercise balls with his cousin.

On this January night, Holly's sister is there, too, having received earlier that day a second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. She inspects the bouquet of pink lilies on the counter, an anniversary present from Chris to Holly.

On the refrigerator, a magnetic pad displays a note from Mya, Holly's oldest.

"I love you Mom, you're the best," the 8-year-old wrote. "The best nurse ever is you."

Despite the sadness and loss of the past year, and with support from family, Holly remains committed to South Seven. She doesn't see how she could leave the ICU at this point, considering how close she and her colleagues have become through all the suffering.

She'll do it for her patients and their families, she says, and to honor Carol, too.

Sometimes, when she's missing her, Holly will watch a video from that weekend at the cabin, where Carol reveled in all the games and boat rides and laughter and love. It shows her mother-in-law, a sprightly redhead, as she dances with her grandchildren, twirling Mya before rushing over to dance with Reed.

Looking back, Chris and Holly say, it seems almost like a send-off.

Intensive care units across Minnesota aren't experiencing as much stress in the new year, which makes Holly want to believe the state is turning a corner with COVID-19. But she's also apprehensive that the pandemic might accelerate once again.

"I want people to know that it can happen to anyone," she says. "We really didn't think it could happen to us — and still, to this day, we're in shock that it did."

PHOTO GALLERY

They've witnessed the worst of COVID-19 – day after day, week after week — while fighting to help grievously ill patients who otherwise wouldn't survive. The pandemic has forced critical care nurse Holly Vilione and caregivers at North Memorial Health Hospital to confront a grueling emotional landscape that's made all the worse when the virus hits home.