George Floyd pleading for his life under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer has become a defining moment of our time.

What began 10 months ago at the corner of 38th Street and Chicago Avenue has transformed into nothing less than an American reckoning on justice, racial equity, the proper role of law enforcement and the historical wrongs society has perpetrated on Black people.

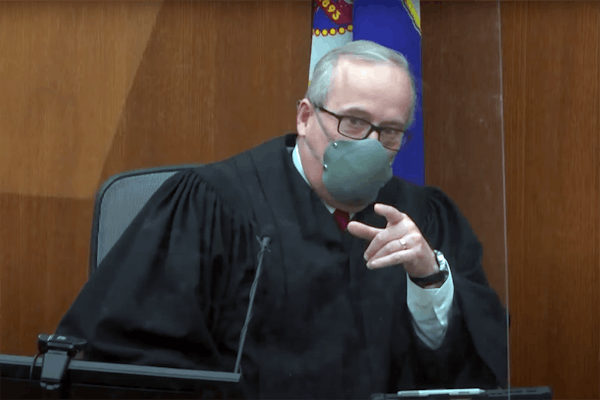

Monday morning, that moment leads to the 18th-floor courtroom of the Hennepin County Government Center, where a jury will begin to hear a murder and manslaughter case against since-fired police officer Derek Chauvin.

The trial itself is about what happened that May evening, but it will also be a vessel into which a splintered society places its rage, anxieties and hopes. Like the trial after Rodney King's beating, like the trial after Emmett Till's murder, like the Scottsboro Boys' trial, this case will be viewed as another chapter — perhaps a turning point — in America's racial history.

"Everything is riding on the outcome of the trial," said Keith Mayes, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota's Department of African American and African Studies. "Yes, Chauvin is on trial, and it's about the Floyd murder. … But an argument can be made it's about all the other folks that didn't receive justice, too. That's why a conviction is necessary for us to reimagine what a future can look like, because these cases continue to happen until the police are thoroughly reformed."

Still, while some look at Chauvin as emblematic of law enforcement as an institution that's misguided at best or racist at worst, others see what happened last Memorial Day as an anomaly: that Floyd's death was the rare exception instead of proof that police are the bad guys.

"I try in my head to better understand that broad-brush mentality, but I have a hard time," said Tim Leslie, the Dakota County sheriff. "If a plumber gets arrested for DUI, are all plumbers drunks? If a pilot crashes a plane, are all pilots incompetent? No. Yet Chauvin does that, he murders somebody, and all law enforcement needs to be reformed. Is that the same?"

History on video

When Mayes saw the Floyd video, the 53-year-old professor had a visceral reaction: What if that were me?

"You almost see yourself lying on the ground with the police officer's knee on your own neck," Mayes said. "You can't help but … be engulfed in this kind of anger and rage and disappointment in the system that continues to allow this to happen."

Growing up in Harlem, Mayes had two distinct types of interactions with police: One with housing police, who were familiar and respectful, and the other with city police, who were feared. Decades later, even as an author with an Ivy League degree, those feelings linger.

After Floyd's death, Mayes joined protests and paid respects at 38th and Chicago. That's how he processed it: by sharing his grief with the grief of the community. He thought about George Floyd, but he also thought about Philando Castile, and Jamar Clark, and Amadou Diallo, the Guinean immigrant killed by New York police while Mayes lived in New York.

"I put this incident along this spectrum of other incidents," he said, "where police either assaulted or killed Black people. And they just get stacked up."

Heroes or villains

For police officers, the national debate about where the profession falls short has often felt jarring and unfair.

"We've disappointed some of our constituency — that's the bottom line," said Leslie, the sheriff in Dakota County. "We have to take a look in the mirror and figure that out."

The past year has been an emotional whirlwind for police. When the COVID-19 pandemic began, they were painted as heroes; after Floyd died, they were painted as villains.

Leslie has tried to think deeply about the issues Floyd's death brought up. He's read books such as "How to Be an Antiracist" and "Uncomfortable Conversations with a Black Man." He's hired a community outreach and equity coordinator, and he's focused more on deputies' mental health.

But Leslie has been in law enforcement for four decades. He knows innumerable police officers who went into the field for honorable reasons. He knows policing is an emotional profession to begin with: seeing dead bodies, dealing with people in crisis, always remaining on edge. The past year has made it more so.

"We're in a really tough spot right now," he said. "We're supposed to deal with people with mental illness, chemical addiction, all sorts of family drama, poverty, undereducated. These are not police problems. These are social problems. We're trying to be everything for everyone, and I'm not sure we're able to do that without disappointing some people sometimes."

Global impact

Chauvin's knee became a symbol of Black oppression worldwide: in Australia and Japan, in France and Germany, in Kazakhstan and Indonesia.

The case "has really become a global indictment of police forces," said Brenda Stevenson, a professor of history and African American studies at UCLA. "This is now representative of what happens everywhere — at least, that's what many people believe. … People are really watching to see if the U.S. can get it right this time."

Thabi Myeni, a 23-year-old law student in Johannesburg, South Africa, had been to plenty of protests before last spring — mostly over racial equity in tuition fees.

When Myeni saw the video of Floyd's death, she thought it would be another example of racial injustice going unnoticed. "I had no idea it would spark a global movement," she said.

What changed for her was when South Africa's ruling party decried Floyd's killing as a "heinous murder." It struck Myeni as hypocrisy. While Americans protested Floyd's death, South Africans were protesting the death of a man named Collins Khosa. Khosa lived in Johannesburg's poor Alexandria township, and he was beaten to death by soldiers who said Khosa had been drinking alcohol in public, a violation of COVID-19 lockdown rules.

After Floyd's death, Myeni organized a march to Parliament. Racial justice protests were sweeping more than 60 countries around the world, but in South Africa, they felt especially resonant. It has been nearly three decades since apartheid ended, and yet institutionalized segregation still has a long tail in South Africa. It was, she thought, no different from America's legacy of slavery and Jim Crow.

"These things are transnational in nature, the global nature of Black oppression," she said. "I think of America as I think of South Africa, where the government — the people of power, the people of privilege — don't want to acknowledge racism still exists."

Policing questions

For some, Chauvin's knee on Floyd's neck told a story of America's history of racism. Calls for an overhaul of policing — to defund or even abolish police — also functioned as calls to disrupt America's power structures.

The reason Floyd's death had more impact than other instances of police violence is simple, said James Mulvaney, a law enforcement professor who worked in New York's Division of Human Rights. Technology made Floyd's death immediate, graphic and personal.

"We're no longer viewing these things through a telescope — we're witnessing them in our living rooms," Mulvaney said. "America watched George Floyd die at our house."

In the months since, police reform has become a heated topic in Minnesota and around the country.

Brendan Cox, the former Albany, N.Y., police chief who now works as Director of Policing Strategies at the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion National Support Bureau, believes the message needs to be the system cannot be fixed by police alone.

"If the community does not trust us not only as individuals but as a system, then we really can't do our job," he said.

Maria Haberfeld, a professor of police science at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City who has written extensively about police training, has been frustrated with the national conversation about policing after Floyd's death. Too much has been driven by loud voices instead of insightful ones, she said. The better discussion, she believes, should have been about centralizing America's police system. Each state having a single police force would help funding and streamline training.

Chauvin "is a classic example of someone who should not be on the job, who was poorly trained," Haberfeld said. "I didn't see all the unrest [Floyd's death] would trigger, but in a way to me I was waiting for something of that nature. I've been writing about this for 20 years. And nobody's been listening."

The cataclysmic national moment that began 10 months ago at the corner of 38th and Chicago will not come to a tidy end at the conclusion of Chauvin's trial. The three other officers at the scene are scheduled to be tried in August, and Floyd's death is certain to reverberate much longer than that.

But Martin Luther King III, the oldest son of the civil rights icon, said he believes the impact of this trial cannot be overstated. An acquittal would mean our criminal justice system must be rethought, he said.

"It may set a tone for how people perceive whether justice can be achieved, specifically for Black people," King said. "Nothing brings this young man's life back. … But his legacy can be that his tragic death mobilized people all over the nation and the world so that we don't go backward, but we as a world community go forward in terms of addressing racial issues."

Tip brings new search for Blaine woman who went missing 30 years ago

Souhan: Fans turned Game 1 into something special. Now bring on Game 2