The Twins' championship teams of 1987 and '91 largely grew up together in the minor leagues, many of them playing for manager Tom Kelly. Their boisterous clubhouse and prideful, long-standing leaders seemed to benefit them in big games.

An eight-year losing streak ended in 2001 when another group of players who had won together in the minor leagues reached the big leagues.

For years, the Twins have honored their World Series champs on every conceivable occasion. They have also celebrated the Twins of the early 2000s, a team that never made it to a World Series.

There is a reason for this. That group of players fought off the dubious threat of contraction, and played the game the way the more romantic among us believe it should be played — with passion, humor, grit and a sense of brotherhood.

With the return of two of the key players of the early 2000s — outfielder Torii Hunter and closer-turned-bullpen coach Eddie Guardado — the Twins' clubhouse this spring was once again loud and funny, after a handful of years during which it resembled a small-town library.

Their return also brought reminders of how those teams embodied the hard-to-define, easy-to-see characteristic that could be called "baseball competitiveness" — a loose-yet-driven attitude that has marked the Twins' best teams.

There was the time in spring training that Corey Koskie loaded David Ortiz's clothes with ice, to distract him from the large dollop of peanut butter in his underwear. While cursing his teammates about the ice, Ortiz made it halfway across the clubhouse before realizing something was amiss. He began screaming at Koskie, threatening to kill him. Koskie and Hunter were already on the floor, laughing.

There was the time that Koskie hid in the back of Hunter's car after a game at the Metrodome. Koskie popped up halfway home and screamed, "Gimme all your money!" "I'm from the 'hood," Hunter said. "I saw something back there and reached down to grab a pen. I almost stabbed Corey Koskie to death. How would that have looked in the newspaper?

"The worst part was I had to turn around and drive him back to the Dome."

Guardado would hassle teammates in the shower. He would also do what could be described as a horizontal cliff dive — he would get a running start and dive on his belly on the shower-room floor, to see how far he could slide.

So one time Koskie sprayed the floor with baby oil without Guardado knowing. Guardado slid so hard into the far wall, leading with his head and shoulder, that Koskie feared he might have damaged an All-Star closer. Guardado lifted his left arm and said, "I can still pitch."

There were more subtle moments that spoke to an unusual dynamic. One day on the road, Koskie, Doug Mientkiewicz, Luis Rivas and Cristian Guzman sat down to watch a movie. All four — the third baseman from Canada, the first baseman from Florida, the second baseman from Venezuela and the shortstop from the Dominican Republic — crammed into a two-person love seat, like kids at a sleepover.

Talent is the most important component to winning in the big leagues, with pitching talent being the most important subset. Roster makeup and organizational depth are vital as well.

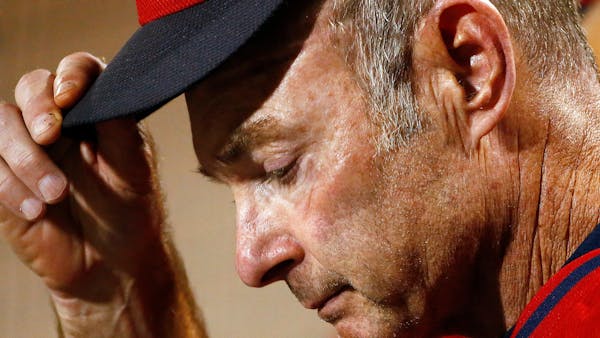

But when you think of good Twins teams, you think of moments informed by personality. Kelly going against his book and leaving Jack Morris in to pitch the 10th. Ron Gardenhire pulling Justin Morneau into an office in Seattle and telling him to straighten himself out, leading to Morneau's MVP run. Puckett telling teammates to jump on his back. Hunter burning his eyebrows off sliding face-first on the Metrodome turf to make a game-saving catch while Guardado exulted. Mike Redmond inventing catch phrases and taking naked batting practice in 2006 as the Twins put together the four best months of regular-season baseball in franchise history.

The return of personality to the clubhouse may not save this team. But it can't hurt.

Jim Souhan's podcast can be heard at souhanunfiltered.com. On

Twitter: @SouhanStrib. • jsouhan@startribune.com

Souhan: Why Tiger Woods should keep swinging

Souhan: Scheffler wins Masters again, shows what makes him special

Morikawa falters in final round at Masters

Keeping up with the Joneses who helped design Augusta National's classic back nine