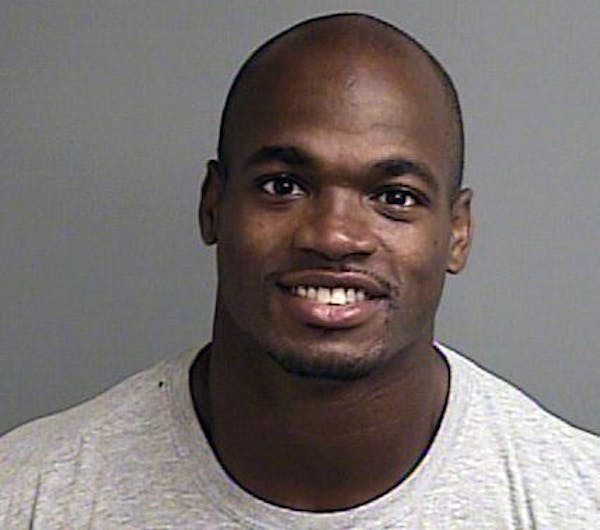

Adrian Peterson told police the "whoopings" he gave to his 4-year-old son came from a switch similar to the ones used on him when he was an east Texas boy, lessons in discipline that he believes helped carve him into an NFL star.

For a Texas grand jury, Peterson didn't carry out a tradition, but an abuse.

Across the nation, the charges against the Vikings star have elicited sharp divisions over when discipline becomes abuse, with social media flooded by sometimes-biting comments.

"I don't doubt a little bit that Adrian Peterson was hit with a switch. I was too," said Jim Bransford, a longtime chemical dependency and family violence counselor in the Twin Cities. "But I never did that to any of my children."

University of Texas associate Prof. Elizabeth Gershoff said the felony charge facing Peterson is rooted in "intergenerational transmission" — when patterns of child raising are repeated, parents using the same methods of discipline they experienced as children.

"Most of these parents are hitting their kids because they think it's the right thing to do and they don't know any other way," said Gershoff, who has researched how parental discipline affects child development and how poverty, neighborhoods, schools and cultures affect children and families.

Peterson's son had welts a week after the beating, which caused a Minnesota doctor to alert authorities. Photos of the injuries that were leaked after Peterson was indicted Friday turned what was a flood of reaction to the case into a tsunami.

Back and forth

Experts said Saturday that what Peterson did is harmful, and undeniably could result in long-term mental health and developmental problems for the child.

But reaction elsewhere was far more mixed and ranged from horror to endorsement of Peterson's approach to child rearing.

"Adrian Peterson has been indicted on a charge of whooping his child with a switch," John Whittaker wrote under @J_Whitty. "My whole family bout to go to jail! Especially Grams. I'm tellin!"

Several pro athletes, including NFL players, recounted their own childhood "whoopings."

"When I was a kid I got so many whoopins I can't even count!" wrote Mark Ingram, running back for the New Orleans Saints. "I love both my parents, they just wanted me to be the best human possible!"

Darnell Dockett, a defensive end for the Arizona Cardinals, recalled a "whippn at 5 with a switch that's lasted about 40mins and couldn't sit for 2days. It's was all love though." He added: "Times have changed!"

People disturbed by Peterson's actions tweeted photos of the boy's injuries.

"I don't care where u r from or how you raise your kids," one man wrote, linking to a photo. "This is not discipline."

Some drew a link between the Peterson case and the domestic violence issue that has marred the start of the NFL season.

"The Adrian Petersons of the world create the Ray Rices of the world," wrote Kris Huson, a St. Paul woman, referring to the former Baltimore Ravens running back seen on video that emerged last week delivering a knockout punch to his now-wife. "Leaving bloody marks and bruises crosses legal line."

Mixed signals

Some took both sides, reflecting the difficulties of the issue. Anthony Tolliver, power forward for the NBA's Phoenix Suns, first took to Twitter to share that "switches & belts probably saved my life growing up."

After seeing the photos of Peterson's son, Tolliver said that he had misunderstood the basis of the case.

"Thanks for the info … was just told he spanked his kid," he tweeted. "Definitely don't support that!" Tolliver added. "Like I said spanking is one thing … that looks very excessive!"

The law itself conveys mixed signals on corporal punishment.

"The line between what's legal spanking and what is abuse is very gray," Gershoff said. "Parents are left to figure it out for themselves."

After Peterson was charged, Montgomery (Texas) County first assistant District Attorney Phil Grant said, "Obviously parents are entitled to discipline their children as they see fit, except when that discipline exceeds what the community would say is reasonable."

In all 50 states, corporal punishment by a parent remains legal. Nineteen states — mostly in the South — allow schools to administer physical punishment to students. Gershoff said it's generally accepted that the line between discipline and criminal behavior is crossed when physical harm to the child remains after 24 hours.

Getting help

Community standards remain a key factor in attitudes toward corporal punishment.

Gershoff's research has shown that African-Americans are more likely to use corporal punishment on their kids and have argued that it's part of their culture.

In a 2012 study, she looked into whether African-American children benefit from physical punishment.

Her finding was that they don't, and that the children suffered the same negative long-term effects as did children of other races.

"I don't think people can keep using that defense when we know any kind of hitting is harmful to children," she said.

Treatment and punishment can be just as fraught. Bransford said Peterson needs treatment from a male African-American therapist who "can talk the same language and respect what he's saying," Bransford said.

He argued that Peterson can get qualified confidential help in Minnesota.

"My hope is the Vikings will show a little bit more wisdom than the Baltimore Ravens," he said.

Gershoff said it's important for parents to understand that hitting a child with an object is not OK. She was also hopeful about Peterson's future.

"I have no reason to believe he is anything other than a parent who wants to do right by his kid," she said. "He can be educated about the harm he's done and still be a good parent."

Rochelle Olson 612-673-1747

Jenna Ross 612-673-7168