On Monday, the United Nations issued its report on the Aug. 21 chemical weapons attack in Syria. With scientific certainty, it confirmed that sarin had been used to kill more than 1,400 Syrians, including more than 400 children.

By design, the report did not assign blame. But the detailed documentation of the munitions and the direction from which they were fired support the conclusion of the United States and other responsible nations: Forces loyal to Syrian President Bashar Assad are culpable in the mass murder.

The report's certitude led U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon to drop his diplomatic caution and candidly assess the situation by saying, "This is a war crime. The results are overwhelming and indisputable. The facts speak for themselves."

If so, U.N. member nations should push for war-crimes charges against those deemed directly responsible. For far too long, the United Nations has been paralyzed by the veto power wielded by China and Russia, permanent members of the Security Council. The report should be a warrant to seek justice and end the civil war. If Russian and Chinese leaders once again use vetoes to shield Assad, they will finally and firmly be revealed for what they are: accomplices.

To its credit, the Security Council is at last working to deal with the immediate crisis of chemical weapons. But it took the threat of a U.S.-led military response to trigger diplomacy. The result was that, on Saturday, Syria agreed to relinquish its chemical weapons — which it had recently and repeatedly denied possessing — by the middle of 2014. Should the country renege on its commitment, the Security Council would determine appropriate international action. Russia, still staunchly backing Assad's homicidal regime, maintains that it will not back military action. Obama and other leaders say that the threat of force, even if outside U.N. auspices, needs to be retained.

That threat was almost defanged by Congress, which seemed set to deny Obama authorization for a military strike intended to deter and degrade Assad's ability to use chemical weapons (even if this strike was to be "unbelievably small," as Secretary of State John Kerry oddly promised). That vote was put on hold after the last-minute U.S.-Russia diplomatic deal.

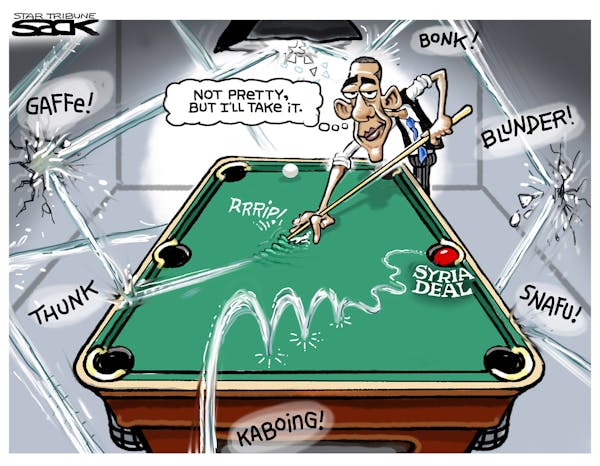

For Obama, the agreement provided a way out of a diplomatic and political problem mostly of his own making. By failing to set a clear strategy from the beginning, he was unable to build international and congressional consensus, which left him mostly isolated on Capitol Hill and at the G-20 summit, where he tried to rally global support.

But in the end, Obama was wise to seize upon the diplomatic opening, however inadvertently it developed. The result, however messy, was that even without an actual U.S. strike, Syria and Russia blinked.

Congressional critics should remember that Assad and Russian President Vladimir Putin did not come clean because of their humanitarian instincts. They have none. They did so to avoid confronting U.S. military might. Had Congress rebuked the president, that threat would have been hollow.

Antiwar sentiment is understandable. But Congress must consider its role carefully, lest it render America's commander-in-chief ineffective. It may, for instance, need to back Obama's plan to arm more-moderate opposition fighters in order to keep the pressure on Syria and Russia to seek a diplomatic solution to the civil war.

The nightmare in Syria goes beyond the illegality and immorality of chemical weapons. The August attack was just a sliver of the slaughter unleashed by Assad: Conventional weapons have killed more than 100,000 and have displaced nearly 7 million. The resulting regional instability risks a wider war that would inevitably involve the United States and other nations.

The chemical weapons crisis may be defused. But the wider crisis of Syria's civil war still needs the world's urgent attention.

The courage to follow the evidence on transgender care

Republicans wanted a crackdown on Israel's critics. Columbia obliged.