Jim Ragsdale

CHICAGO – Grim statistics about gun violence, hyperclose readings of the Second Amendment, and data sets describing the nation's special relationship with firearms overflowed my aging brain at a seminar on guns last week.

Then someone handed me a Glock.

There suddenly was only one overriding truth and it was exploding in my hands, like a tiny cannon. I held on as my kindly gun-range instructor urged me to breathe deeply and squeeze gently.

"Good, good," he kept saying, but I felt like I was holding on for dear life.

"Covering Guns" brought reporters with front-line experience covering mass shootings in Tucson, Ariz.; Aurora, Colo.; Newtown, Conn., and Red Lake, Minn., to meet with gun experts and advocates and gun trainers. Sponsored by the Poynter journalism center and funded by the McCormick Foundation of Chicago, we gathered in a city that witnessed 506 homicides last year.

U.S. Supreme Court victories by gun advocates; a Chicago Crime Lab bar chart of victims, in which the column for young African-American males spikes as tall as what they used to call the Sears Tower; the way Congress has cracked down harder on the federal agency that regulates guns than on those who sell guns without background checks; even the unavoidable fact that the U.S. homicide rate towers over those of other developed nations — all paled next to an encounter with the real thing.

A team led by Don Haworth, a Chicago private investigator and firearms trainer, explained the components of a round, the various sizes of ammunition magazines, even the spiral etching inside the barrel that spins the bullet for accuracy and leaves a ballistic fingerprint. Haworth displayed the cavity of a hollow-point bullet and showed with his fingers how it would shatter and spread should it enter my chest.

"I bet the surgeons loved them," I said.

Haworth, who carries a weapon in his PI work, said he once drew on three unarmed men who were threatening him. They let him pass and he did not have to shoot. He said a person shouldn't carry a gun without first deciding he or she is willing to pull the trigger when the time comes.

Maybe that explains the tension between "gun people" and "gun control people": The controllers believe the gunners have answered Haworth's question in the affirmative, and therein lies a philosophical divide.

Haworth said the smooth-looking Glock was "locked and loaded" when I had clicked in a filled magazine and slid a round into the chamber. But I felt no sense of "gun control" — not much better than the member of our party who screamed and dropped the weapon on a table after it fired.

My reeled-in target of a human form with holes in the upper chest and arms showed, to my surprise, that I hung on well enough. I could see how that unmistakable bang and kick and focus on the target creates a rush of its own, in the sporting and nonviolent sense. The trainers' care and caution were a strong endorsement for responsible gun ownership and training.

But no one disputed the fact that some of our 270 million guns inevitably leak into Chicago and north Minneapolis and also into the hands of people who are the emotional opposite of Haworth and our coolheaded trainers. The Chicago Crime Lab's numbers show that U.S. residents are no more crime-prone on non-gun measures than, say, Londoners. We lead the world in gun ownership, and England has few firearms in private hands. It's difficult to get shot in the England.

I left Chicago wondering whether there is any middle ground — if we can have our Glocks and our ranges and our permits to carry without that Sears Tower of tragedy.

The "Covering Guns" presentations and data are available at coveringguns.com.

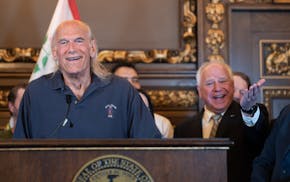

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president

Dave Kleis says he won't run for sixth term as St. Cloud mayor

Newspaper boxes repurposed as 'Save a Life' naloxone dispensaries

St. Cloud house vies for Ugliest House in America