Today's Republicans are very good at tending the fire of Ronald Reagan's memory, but not nearly as good at learning from his successes. They slavishly adhere to the economic program that Reagan developed to meet the challenges of the late 1970s and early '80s, ignoring the fact that he largely overcame those challenges, and now we have new ones. It's because Republicans have not moved on from that time that Sens. Marco Rubio and Rand Paul, in their responses to the State of the Union address last week, offered so few new ideas.

When Reagan cut rates for everyone, the top tax rate was 70 percent, and the income tax was the biggest tax most people paid. Now neither of those things is true: For most of the last decade, the top rate has been 35 percent, and the payroll tax is larger than the income tax for most people. Yet Republicans have treated the income tax as the same impediment to economic growth and middle-class millstone that it was in Reagan's day. House Republicans have voted repeatedly to bring the top rate down still further, to 25 percent.

A Republican Party attentive to today's problems would work to lighten the burden of the payroll tax, not just the income tax. An expanded child tax credit that offset the burden of both taxes would be the kind of broad-based middle-class tax relief that Reagan delivered. Republicans should make room for this idea in their budgets, even if it means giving up on the idea of a 25 percent top tax rate.

When Reagan took office, he could have confidence in John F. Kennedy's conviction that a rising tide would lift all boats. In more recent years, though, economic growth hasn't always raised wages for most people. The rising cost of health insurance has eaten up raises. Controlling the cost of health care has to be a bigger part of the Republican agenda now that it's a bigger portion of the economy. An important first step would be to change the existing tax break for health insurance so that people would be able to pocket the savings if they chose cheaper plans.

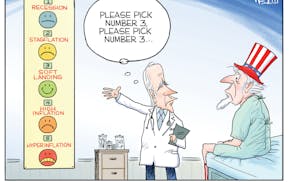

Conservative views of monetary policy are also stuck in the late 1970s. From 1979 to 1981, inflation hit double digits three years in a row. Tighter money was the answer. To judge from the rhetoric of most Republican politicians, you would think we were again suffering from galloping inflation. The average annual inflation rate over the last five years has been just 2 percent. You would have to go back a long time to find the last period of similarly low inflation. Today nominal spending — the total amount of dollars circulating in the economy both for consumption and investment — has fallen well below its path before the financial crisis and the recession. That's the reverse of the pattern of the late 1970s.

Trying to boost economic growth through looser money is usually a mistake, as Reaganites rightly argued. They were right, too, to think that the Federal Reserve should make its actions predictable by adhering to a rule rather than improvising depending on its assessment of current conditions. The best way to put those impulses into practice is to require the Fed to stabilize the growth of nominal spending. That rule would allow looser money only when nominal spending is depressed. This is more or less what the Fed did from 1984 through 2007, a period that Republicans sometimes call the Reagan boom (since they see Bill Clinton as having largely kept his policies) and that economists generally call the Great Moderation. Relatively stable nominal spending growth promoted relatively stable economic growth, and it can again.

The Republican economic program of the 1980s also fought against government-imposed restrictions on economic activity: decontrolling energy prices, for example. Today we should target different restrictions. Software patents have become a source of unproductive litigation that entrenches large tech companies and inhibits creativity. Republicans shouldn't support those patents. Economic growth has to trump corporate executives' campaign donations.

Conservatives should retain their skepticism about government intervention, the preference for letting markets direct economic resources and the zeal for ending government-created barriers to economic growth that they inherited from Reagan. In his first inaugural address, Reagan famously said that "government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem." The less famous yet crucial beginning of that sentence was "in our present crisis." The question is whether conservatism revives by attending to today's conditions, or becomes something withered and dead.

--------------

Ramesh Ponnuru is a columnist for Bloomberg View and a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He wrote this article for the New York Times.