This story has a happy ending, but it took 6 1/2 years.

In October 2006 Joan Najbar opened her mailbox one afternoon and found a returned letter she had sent two weeks earlier to her son serving in the Army National Guard in Iraq. In red letters, the envelope was stamped "DECEASED."

A frantic Najbar found out later that night that her son was still alive. But the Duluth woman never was able to determine who had stamped the word on the letter, or if it had ever even left the Duluth post office.

Her son has since left the military and is safe back home. Postal inspectors and the Office of the Inspector General investigated but could never conclude the origin of the stamp on the letter. But Najbar never let go.

A malicious stamp on a letter may seem like a small thing, but its symbolism had broader implications about how a government behaves when it is at war and only a small percentage of its citizens are doing the fighting.

It was right before the 2006 election. She was active in the antiwar movement at the time. Other mothers she was working with in opposing the war received death threats and harassing late-night phone calls.

"If we are a nation of war, we need to act like it," Najbar said. "I couldn't handle it if it happened again. You are a government agency handling soldiers' mail during wartime, you better get your act together. What it said to me was that soldiers and their families are invisible."

She sued the Postal Service in 2009, saying she experienced emotional distress and lost income. In 2011, an appeals court ruled that she couldn't sue for what happened because the Post Office was immune from liability. The court did admit in its ruling that she "was injured in an uncommon way, one in which we might not ordinarily expect the Postal Service to injure its customers."

It was never about the money, she said.

Earlier this month, a letter came from the Postal Service to U.S. Sen. Al Franken's office, which had taken up the case at Najbar's request. It reiterated that an investigation had never been able to determine at what point the stamp was placed on the letter.

"The mishandling of the mail is certainly unintentional and we work very hard to eliminate such mistakes when brought to our attention," wrote Anthony C. Williams, district manager for customer service and sales of the Northland District. "We do not take these matters lightly and will try to ensure a situation such as the one that Ms. Najbar experienced does not happen in the future."

But it contained more: "Please extend our sincere apology to Ms. Najbar."

They were the eight words she had been fighting for.

A spokesman for the Postal Service said it is standard procedure to send a response to a congressional office making an inquiry for a customer, so it did not send a letter personally to Najbar.

She said she was thankful it happened at all. "To me this was just, you don't disrespect our servicemen and women in this manner. It's like the bully in the playground, only the bully is your government and they can't say they are sorry," she said. "At least they are saying in this letter, 'OK, we'll pay attention.' That's all I want."

Mark Brunswick • 612-673-4434

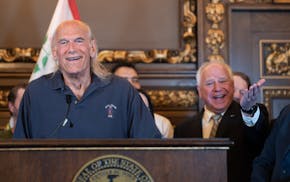

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president

Dave Kleis says he won't run for sixth term as St. Cloud mayor

Newspaper boxes repurposed as 'Save a Life' naloxone dispensaries

St. Cloud house vies for Ugliest House in America