Hofesh Shechter Company's "Political Mother" is not easily forgotten -- and could likely spark a spirited debate. Presented Tuesday night at the Orpheum Theatre in Minneapolis by Northrop Concerts and Lectures with the Walker Art Center, the 2010 production proved positively Orwellian in its unsettling depiction of what happens to a society -- and individual free will -- when power goes unchecked.

Shechter, an Israeli-born choreographer and musician now based in Great Britain, relies upon his hard-driving metal-inspired rock score played live by a disciplined band (drilling guitars, with pounding bass and drums) to propel 12 performers through movement using elements of the folk dancing he learned in his youth filtered through the considerably more rugged but still communal experience of the mosh pit.

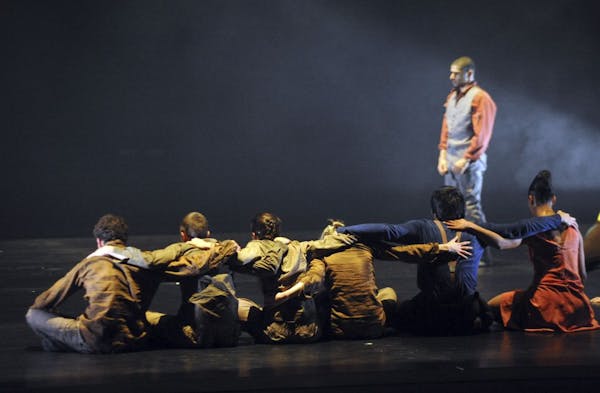

The troupe (with members from several countries) was flat-out fantastic and stirringly cohesive, dancing with an urgent sense of survival, their limbs loose with a paradoxical shambling grace, kicking feet in constant motion, heads hung a bit between hunched shoulders and arms often raised, either in submission or triumph -- as the moment required. They generated a maelstrom of motion within a shadowy space lit by Lee Curran, one that served well Shechter's cinematic vision of a dystopic world.

The dancers' bodies were seismic maps, trembling and quaking, often in response to a charismatic vocalist whose guttural shouts were passionate but intentionally garbled. A thread of violence (threatened or realized) ran throughout the work. This was most apparent in the dancers' beaten-down aspect as well as the occasional firing-squad-style line-ups or small yet poignant rebellions. Even Samurai warriors played a ghostly role -- with one committing ritual suicide in the opening scene.

"Political Mother" packed a punch but didn't always connect. Shechter wisely varied the raucous metal vibe with more delicate strings on a soundtrack (his musical collaborators are Nell Catchpole and Yaron Engler), but the work grew repetitious.

And also surprisingly sentimental, with a message broadcast across the back wall -- "Where there is pressure there is folkdance" and Joni Mitchell's reflection on love, "Both Sides Now," played at the end. Maybe Shechter held out hope for empowerment but his depiction of the struggle against oppression was so indelible that the reward of relief felt too easily obtained. Then again, perhaps this illusion was his point. As the work's maker, he too is capable of manipulation.

In heated western Minn. GOP congressional primary, outsiders challenging incumbent

Minnesota Sports Hall of Fame: A class-by-class list of all members

This retired journalist changed professional wrestling from Mankato