Thousands of frail Minnesotans who plan to move into assisted living facilities will have to talk with a telephone counselor first under a state law that takes effect Oct. 1.

The counseling is designed to help older people and their families make better -- and less costly -- long-term care choices. It also is projected to save taxpayers $3.8 million in the next two years because public programs such as Medicaid pick up much of the bill for long-term care.

But it has kicked up a fuss among the state's 1,701 assisted living operators, who could lose customers.

The popularity of assisted living has exploded over the past two decades, from zero to 62,000 residents -- twice the number now in nursing homes. About 30,000 Minnesotans each year make the move. Lawmakers have become increasingly concerned about the burgeoning costs of public programs to care for frail people, whether at home, in nursing homes and recently in assisted living.

But while the average yearly cost for an assisted living apartment in Minnesota now is $37,000 -- well below the $67,000 on average for more intense care at nursing homes -- it's far more expensive than remaining at home. While about one-third of residents pay privately for nursing home care, about 85 percent pay their own way in assisted living.

As a result, some people exhaust their savings in assisted living and shift onto a Medicaid-supported program called Elderly Waiver, which subsidizes their costs. Of the 62,000 people in assisted living, about 7,875 are on that program, each at an average annual cost of about $26,000.

With the counseling, the state estimates that 945 callers a year will choose a cheaper option, most likely staying in their homes with added services.

"Our surveys have told us that people want this kind of information" to help them maintain a high quality of life as they age, said Loren Colman, assistant commissioner for continuing care at the Minnesota Department of Human Services. "This will be very helpful for many older Minnesotans and their families."

'Government overreach'

Giving advice and information is a good idea, critics in the senior housing industry agree, but they argue that it shouldn't be mandatory and must come far earlier to be effective.

"This is government overreach," said Eric Schubert, vice president for public affairs at Ecumen, among the state's largest providers of nonprofit senior housing, with 37 assisted living facilities serving 2,000 residents.

"People do need good information about long-term care options, but don't make it mandatory counseling just when they're decided to move. It's not effective and it's ageist," he said.

"Older people can buy a house or move to Arizona, but now they need counseling to move into assisted living?"

Deb Holtz, the state's ombudsman for long-term care, says the industry has done a far better job than previously in screening new residents to ensure they can afford the care.

"But when it comes to giving unbiased information about your range of choices, the state is very effective," she said. "Most people have no idea what services are available, then have to scramble when they hit a crisis."

State officials and critics agree that people would make better choices if they got information earlier, perhaps in workplace programs.

"I tell my clients that their home is the cheapest housing they'll find," said St. Paul elder law attorney Julian Zweber. "But most people move into assisted living because they need extra help. By that time, counseling probably won't make much difference."

How it works

Starting next month, before people sign a lease for assisted living, called "housing with services" under Minnesota law, they must call the Minnesota Senior LinkAge Line (1-800-333-2433) for counseling about their care options. At the end, they will be given an 11-digit "verification code" number, which also will be sent to them in the mail.

People may refuse the counseling, but still must talk with a counselor and obtain a code number. Only those entering government-subsidized assisted living will not need one.

The call itself may take five to 10 minutes, longer with more complex situations. The counselors, all with degrees in social work, nursing or a related field, ask seven screening questions to help determine a person's risk of needing nursing home care.

Callers will be offered information about programs that might help with daily activities, and about 6 percent with high needs -- perhaps 1,800 over a year -- will be linked to county social service professionals for a face-to-face evaluation.

Colman pointed out that the new program is an extension of a voluntary service the state has offered for years.

"We want to give people the information they want so they can make good choices," he said.

Warren Wolfe • 612-673-7253

Legendary record store site in Minneapolis will soon house a new shop for musicheads

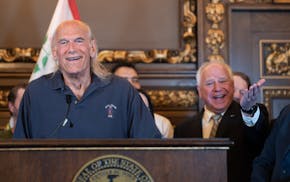

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president

Dave Kleis says he won't run for sixth term as St. Cloud mayor

Newspaper boxes repurposed as 'Save a Life' naloxone dispensaries