Cult leader Victor Barnard is long gone from Minnesota, but his shadow hangs over Pine County, where the two-year wait to press charges against the disgraced pastor is shaping the race for county attorney.

County Attorney John K. Carlson is retiring this year after three decades as Pine County's top prosecutor. The race to replace him has sparked a bitter debate over how crimes are prosecuted, and how many criminals ever see the inside of a courtroom in this rural county midway between the Twin Cities and Duluth.

"It is a frustrating ordeal to get a crime charged in this county," said Pine County Sheriff Robin Cole, who is retiring in December after four years of rocky relations with the county attorney's office. "It's a battle to get any serious crime prosecuted."

According to the Minnesota Department of Public Safety, Pine County cleared, or solved, 46 percent of the criminal cases it handled in 2013. Of the 2,197 major, minor and juvenile criminal cases the county attorney's office handled that year, 11 of them made it to a jury trial.

Those statistics say very different things to the two prosecutors running to replace Carlson.

Chief Deputy Pine County Attorney Steven Cundy has spearheaded the county's criminal prosecutions for the past decade and now hopes to head the office. Challenging him is Reese Frederickson, a Pine County attorney who works as a prosecutor in neighboring Kanabec County — a county half the size of Pine, but with double its case clearance rate.

Prosecuting vs. winning

"The Pine County attorney's office takes every case very seriously," said Cundy. A self-described "straight shooter and a realist," Cundy says he's battled the county's slow-moving court system himself and understands victim frustration. But when prosecutors opt not to pursue a case in Pine County, he said, it's for solid reasons. The goal, he said, is to "bring forth every case that you think you can prove beyond a reasonable doubt."

Frederickson, on the other hand, says prosecutors should be willing to put themselves on the line and push aggressively for jury trials. An Air Force veteran, he has been working as a prosecutor in Kanabec County for the past seven years, where, according to the Department of Public Safety, the case clearance rate tops 98 percent.

Right now, he said, he's prosecuting a case in his county involving a child who was sexually molested in Pine County. The victim's family contacted him after Pine County declined to prosecute.

"It's shocking," said Frederickson, who said he researched Pine County felony conviction rates and found that 45 percent were dismissed the day of the trial. "I don't think I've ever dismissed a felony, and I've done everything from speeding tickets to homicides here."

Cundy disputes that the case fell within his jurisdiction, and the Pine County attorney's office disputes that dismissal rate figure. By their count, the office has had 391 felony referrals in 2014 and declined to prosecute a quarter of them — turning down 98 cases so far this year.

Cole, the retiring sheriff, said his investigators have been frustrated by prosecutors they felt didn't push hard enough on cases like the man who raped and impregnated his 11-year-old stepdaughter; or the woman who shared a lethal amount of methadone with her boyfriend; or the man who terrorized the county with envelopes of mysterious white powder, bomb threats and fake explosives.

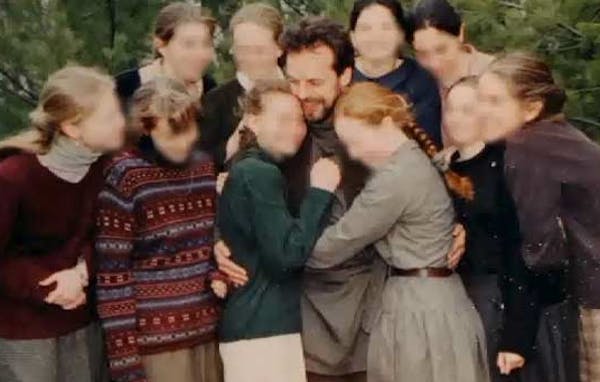

But for critics like Cole, no case better sums the county's problems than the case of Victor Barnard — a charismatic preacher who took young girls he dubbed "the Maidens" away from their families and allegedly molested them for years in a remote Pine County enclave.

The sheriff's office conducted a detailed investigation of the Maidens case, including witness statements from two young women who said they were molested by Barnard when they were 12 and 13 years old, the case went into two boxes that "sat on Steve Cundy's office floor for two years." The office brought charges against Barnard in April. Barnard is believed to be in hiding in Washington state.

"It's been frustration after frustration after frustration," Cole said. "It's catch and release. … We have been dealing for the past four years with 22- and 23-year-olds who spent their late teens on crime sprees and were never dealt with, never faced consequences."

Cundy counters that he worked hard to bring charges against Barnard but was frustrated by a lack of cooperation from witnesses. He takes pride in the big cases his office has pushed — homicides, drunken drivers and a serial arsonist who went on a cabin-torching spree.

Track records debated

Sparsely populated Pine County sprawls across 1,400 square miles of farms, forests, rolling hills and close-knit towns. Soon after Frederickson moved to Sandstone with his family seven years ago, he said he began hearing grumbles about the county's track record on prosecutions.

"In the area where I live, there are certain repeat offenders who continue to do the same crimes," he said. "The sheriff's department has had them in their clutches, to the point where they could go to prison, but the current administration always gets a plea deal, puts them on probation."

Cundy, 50, argues that he has far more prosecutorial experience than 38-year-old Frederickson.

"To my knowledge, he's never even prosecuted a homicide," Cundy said. Frederickson said he was part of the team that prosecuted a 2009 double homicide.

Frederickson says the number of years on the job is less important than what you do with those years. "I've played baseball longer than Joe Mauer, but that doesn't mean I'm better," he said.

Jennifer Brooks • 612-673-4008