Minnesota homeowners facing the loss of their houses could stop foreclosures and make reduced payments for up to one year under a bill that will get its first legislative hearing today.

"It's time for bold, balanced actions," Rep. Jim Davnie, DFL-Minneapolis, said at a news conference Wednesday. "It's time to prevent avoidable foreclosures in Minnesota."

Minnesota's actions are being closely watched elsewhere, as few states have attempted a widespread freeze on foreclosures since the Great Depression.

Foreclosures are expected to reach a record 33,000 in Minnesota this year, up from 20,573 last year, said Sen. Ellen Anderson, DFL-St. Paul. And while Hennepin County is the hardest hit, foreclosure signs are popping up across the state as borrowers succumb to a weakening economy.

Anderson, chief sponsor of the Minnesota Subprime Foreclosure Deferment Act in the Senate, said, "It's going to offer breathing room."

And, she said, "it will offer an alternative to lenders who do not want to be in the real estate business."

The measure (HF3612, SF3396) would allow homeowners with subprime loans to pay roughly 65 percent of their monthly mortgage payments, deferring the remainder for one year.

Homeowners would have to live on their properties during that year, and even one missed or late payment could restart foreclosures.

Davnie estimated that up to 15,000 homeowners could be helped by the proposal.

Depression-era case

Interestingly, back in the Depression, a Minnesota moratorium on foreclosures set a precedent in a case that was fought all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The 1934 decision in the Home Building and Loan Association vs. Blaisdell broke new ground with its finding that states had the ability to address foreclosure problems even if it meant intervening in private contracts.

Prentiss Cox, a professor at the University of Minnesota Law School who researched and helped draft the current legislation, said, "There is no question this is constitutional."

Davnie, the House sponsor, said the proposal is far-reaching, but does not go as far as Blaisdell, calling it a foreclosure "deferment" rather than a moratorium.

Lenders nervous

The measure could affect lenders across the country, requiring them to accept partial payments and defer actions on defaulted loans with little promise that they could recoup their losses.

Some lenders sounded warnings Wednesday that the proposal could have unintended consequences and result in fewer lenders willing to do business in Minnesota.

Steve Johnson, spokesman for the Minnesota Bankers Association, said his organization has concerns about the bills, but has not taken a position yet.

"We don't want to be in the real estate business," he said. "I'm just not convinced that this is the way. I know there are concerns about the constitutionality of this. It could be an interference of contracts."

One of the people at Wednesday's news conference was David Williams, 52, who had lived in his modest Minneapolis home since 1989. Barely literate, Williams spends much of his time caring for his 84-year-old uncle.

On Wednesday, Williams said that three years ago he was enticed into a subprime refinancing of his home to install new windows and a ramp for his disabled uncle. When the time came to sign the papers, Williams said, "it was a whole different loan. It was crazy. I didn't know nothing about balloons [payments]." He began falling behind in his payments. The lender foreclosed and a sheriff's sale is scheduled for later this month.

"I trusted somebody and I got screwed," Williams said.

House Minority Leader Marty Seifert, R-Marshall, said Republicans will strongly oppose the measure, although he acknowledged that they lack the votes to stop it.

"Our financial markets are based on personal responsibility," Seifert said. "If we start to go down this road, where does it end? Do we give year-long deferments on student loans, car loans, credit card debt? I just think it's a slippery slope. If you buy more than you can afford, you have to calculate the risk. I'm not sure government can be your savior every time."

Don Brewster, vice president of Origin Financial, a Michigan-based lender that does business in Minnesota, called the proposal "ill-advised."

In many cases, he said, it will delay the inevitable while tightening credit for responsible borrowers. "Most people who go into default have lost their jobs or have severe financial problems," he said. "It's a convenient excuse on the part of consumer advocates to say that the lender is always at fault, but whether it was a wise or unwise decision, most of these people knew exactly what they were doing."

Brewster, who noted that his company does not make subprime loans, acknowledged that fraud is a factor, "but I have a hard time with the notion that consumers were somehow duped." Paying off high-interest credit card debt with a refinanced mortgage "was not an irrational decision for many people," he said.

Unintended consequences?

Being forced to accept partial payments and deferred foreclosures, he said, could motivate lenders to become even more aggressive on any late payments.

Most lenders allow 60 to 90 days before issuing default notices, he said, "but if you know you're looking at a year where you can't take action, they might start sending them out right away. You could even see some lenders withdrawing from the Minnesota market."

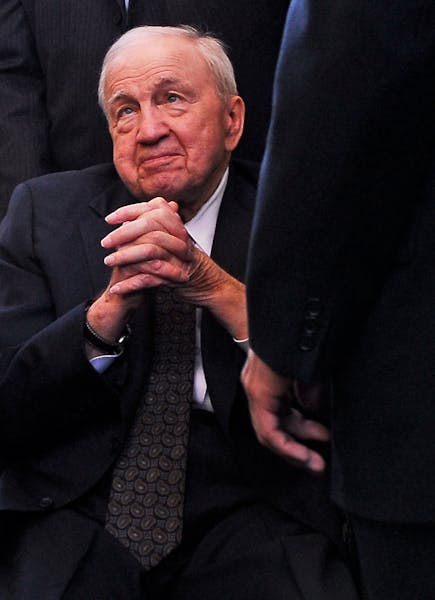

Art Rolnick, senior vice president for the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, said that the bill is "a bit unprecedented in modern times" and that government should move forward with caution.

"If you can keep someone in their house, that's a good thing, from a public policy perspective," he said. "But there could be unintended side effects. There is reason for government to step in, but it should, perhaps, be limited to low-income borrowers who were misled."

Patricia Lopez • 651-222-1288