"Have we gone insane?" is what a Minnesota cattle farmer probably not much interested in March Madness asked. His question was a reaction to the news that Jerry Kill, the University of Minnesota football coach, had his $1.2 million salary increased to $2.1 million, plus perks, for guiding the Gophers to eight wins and five losses during the 2013 season. Maybe winning isn't everything. It certainly isn't for everyone.

No doubt Coach Kill is a nice enough guy and competent enough at what he does. And he didn't complain about the salary bump he received. Ohio State's Urban Meyer makes $4.6 million, plus perks, and he's in the same league.

It's hard to imagine anyone in his or her right mind seriously believing that the NCAA Division I big-money sports — football, basketball, hockey — have anything but a tendril connection to a university's higher-education missions. There are several fine student-athletes who get excellent grades while working very hard at their sports. The graduation rate for athletes and nonathletes is comparable, though the amount of money it takes to get a student-athlete a degree is hidden in a murk of red ink. But it seems obvious that the hazards of football seem well out of line with what health educators teach, and that at the D-1 level students need to learn how to keep their classes from interfering with their serious sports jobs.

Student-athletes must suspect they're part of an entertainment industry. Coach Kill was honest enough to fess up to it, and he left the impression that as a newcomer to the industry his new salary represents his fair market value.

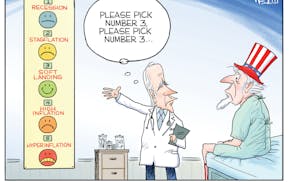

But some of the people responsible for overseeing the numbers at D-1 higher-educational institutions maybe need some refresher courses in elementary arithmetic. Only 23 of the 228 NCAA D-1 sports programs generated enough income to cover expenses in 2012, and 16 of the 23 winners received subsidies by way of student fees and university and state funds. The other 205 were losers, as were the donors and taxpayers who picked up the tab. Losing seasons are a financial trend for most NCAA schools.

Meanwhile, the NCAA as an organization quietly showed a profit of $71 million for 2012. Meanwhile, rather noisily, state governments try to figure out how to pay their bills.

It's time to turn these big-time sports teams into what they really are: Businesses. Because I'm addicted to thrift, I think they should get off an unsustainable welfare system. Privatize them.

I'm not a spoilsport. I know that millions love to cheer for the logos and colors on the laundry they love. Big-time sports are major rituals that stimulate a deep need for community identity. As a kid in Michigan, I grew up loving the Spartans and Wolverines, and I got my graduate degrees as a Buckeye at Ohio State. When I married a Nebraska woman, I learned to love Cornhuskers, and because I pay taxes in Wisconsin, I have a Badger in me, and because my daughter is a student at the University of Iowa, I'm a Hawkeye, too. As a Minnesotan, I'm a devout Gopher, for reasons I can't fully explain. I want everyone to win.

A lot of people are not ready to give up big-time collegiate sports, even when they go home from a game as losers again.

Turning big-time collegiate sports programs into for-profit enterprises should especially appeal to fiscal conservatives who have a passion to cut taxes and privatize the public schools.

Here's my business plan: Turn the big-time intercollegiate sports over to private entrepreneurs willing to invest in new business ventures. Let entrepreneurs, rather than participating schools, run them as private for-profit businesses. They buy the naming, branding and concessions rights from universities. They lease the cheerleaders and marching bands. They lease university facilities, or construct their own. They pay all travel and advertising expenses. They cut their own TV and bowl game deals. They hire the coaches and other managers. They pay the bills and enjoy the profits that come rolling in. Private investors could get involved, and maybe Wall Street, too.

Could these new business enterprises — let's call them clubs — still be considered intercollegiate sports? A few rules would give them permission to say yes. The players would be recruited from the pool of graduating high school student-athletes, as they are now. They would have five years to fulfill four years of service on the playing field. They would be required to establish student identity by taking at least one class at the university whose logo they wear during games.

Nothing much would change, except the ownership of teams, business plans and bookkeeping responsibilities. Gopher fans could continue to cheer for players wearing Gopher uniforms, and everyone could continue to have a good time.

Currently, there's some talk about student-athletes unionizing. That's an issue players could work out with management, maybe after some discussion about salaries for coaches and club executives. Clubs, as free-enterprise businesses, could make millions, or not. And if not, owners could downsize or apply other lean strategies.

Already there are rumors about the University of Minnesota needing $190 million for improved practice facilities. Experts feel that the U will not be able to compete without the upgrades. They're very probably right. Why would an 18-year-old superathlete high school recruit want anything but the latest and best high-tech facilities? Why not go to Penn State instead?

Tim Dahlberg, sports writer for the AP, says, "That's the way things are in big-time college athletics, where the rich are getting richer. Hard not to profit when the labor is free." Hard not to profit when public university athletic programs are bailed out by student fees and tax dollars.

I'm with the cattle farmer from western Minnesota. Why play this game? "Have we gone insane?"

Four or five times a year I get a call from sweet-voiced students at my alma mater Ohio State. They want me to send OSU money, because there's never enough to go around. I plead with them to spread the word: For starters, I tell the voices on the line, cut the coaching salaries in half. Call me again after you begin there.

Emilio DeGrazia, of Winona, Minn., is an emeritus professor. This article was first published by Twin Cities Daily Planet.

Lab-grown beef is red meat for the conservative base