On Tuesday, Pakistani Taliban thugs tried to assassinate a 14-year-old girl. You read that correctly: Masked gunmen from the ultra-purist Islamist group stormed a van full of schoolchildren in an effort to kill Malala Yousafzai, who has won international acclaim for going to school in defiance of Taliban edicts against educating girls in her home region of Swat.

With chilling pride, a Taliban spokesman announced that the attack was revenge for Malala's having generated "negative propaganda" about Islam; he called her an "obscenity." That strikes us as an apt description of the attack itself; if anything is causing a negative view of Islam around the world, it is the Taliban's attempts to impose a medieval social order on Pakistan and Afghanistan.

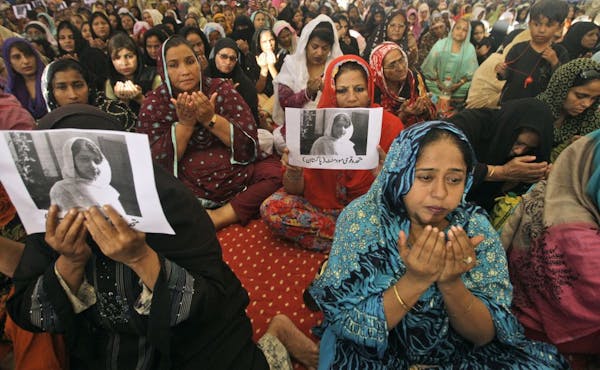

At last check, Malala, though critically wounded, was expected to survive. The larger question, of course, is whether the progress she both embodied and sought to extend will prove lasting. The Taliban struck this brave youngster at least in part because it knows that she may represent the wave of the future. She enjoyed significant popularity in Pakistan, as shown by the condemnation that rained down on the Taliban from the highest levels of the government and from the country's media.

For all its woes, Pakistan has shown measurable progress in educating girls. Pakistani females ages 15 to 24 were half as likely as males to be literate in 1990; in 2009, that ratio had improved to three-quarters, according to the United Nations. Alas, the greatest obstacles to girls' schooling exist in rural areas where the Taliban and other extreme groups maintain a presence.

A similar drama is playing out across the border in Afghanistan. In May, the Ministry of Education said that 550 schools in 11 Taliban-plagued provinces had been forced to close their doors. And in 2011, 150 girls fell ill at a school near Kabul, in an apparent mass poisoning by foes of female education.

The Obama administration has repeatedly said that it is open to a negotiated settlement to the Afghan conflict - but only if the Taliban agrees to abide by Afghanistan's constitution, including its protections of women's and minority rights. So far, of course, talks have not even begun. Taliban hard-liners seem content to wait until after 2014, when the United States is scheduled to finish withdrawing from Afghanistan.

In December, Vice President Joe Biden publicly summarized the administration's rationale for negotiations, noting that "the Taliban per se is not our enemy." This was reasonable, to the extent Biden was simply saying that the United States could deal with the Taliban, or elements of it, that agrees to repudiate al-Qaida and respect the constitution.

The vile attack in Pakistan, though, reminds us that enmity is a two-way street, and the Taliban still hates the United States and everything it stands for - whether we like it or not. According to the Taliban spokesman, one of Malala's worst sins was to "consider President Obama as her ideal leader." It might never be possible to strike a deal with such people. It should always be possible for the United States to help protect innocents from them.

The little park that could … be better

Climate change looms large this election year

For this Minnesota legislator, action targeting child abuse is intensely personal