As I drove to church one Sunday afternoon, I turned the corner to the ramp to the freeway, only to encounter two potholes spaced in such a way that I could not avoid them. I was only going about 25 to 30 miles an hour, but the horrible noise made my entire car shudder -- and made me wince.

"Pothole or person?" I quipped to my 16-year-old son, who had briefly looked up from his magazine. My quip belied the reality I knew. Of course it was a pothole; I saw it before I hit it.

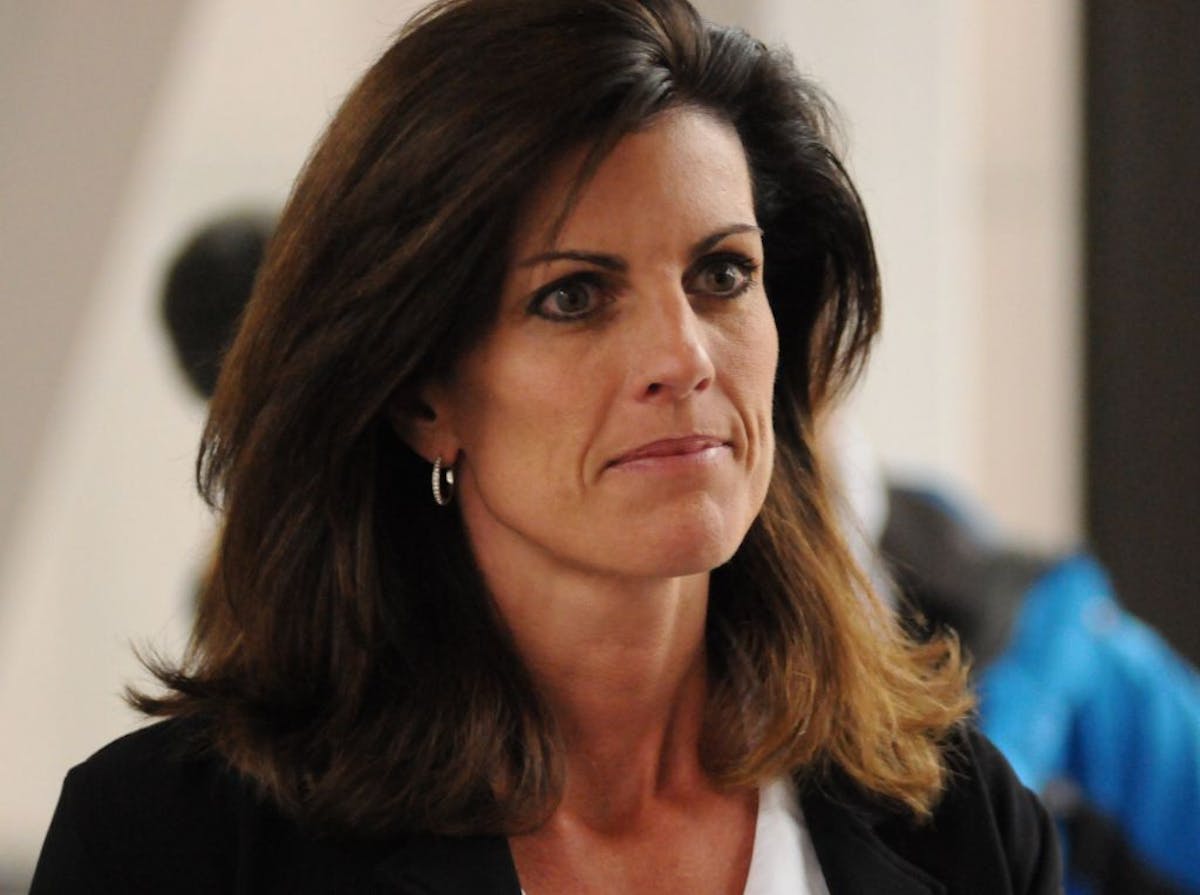

But Amy Senser testified that she did not recall seeing Anousone Phanthavong's vehicle and thus did not, and could not, associate the sound she heard with hitting anything but what her experience told her was normal and her conscious mind was aware of -- a pothole.

In his book "Thinking, Fast and Slow," psychologist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman uses years of psychological and behavioral research to develop two conceptual constructs of the mind: System 1, intuitive and emotional (Fast), and System 2, deliberative and logical (Slow).

These constructs distinguish which part of the mind influences our thoughts and behavior.

Kahneman asserts: "System 1 is designed to jump to conclusions from little evidence -- and it is not designed to know the size of its jumps," because it does its work outside our conscious awareness. In another passage, he writes: "When uncertain, System 1 bets on an answer, and the bets are guided by experience."

Senser admitted her uncertainty in her testimony: "I've never been in an accident, so I wasn't quite sure if I'd hit a pothole or one of those construction signs. I wasn't sure what it was" ("Amy Senser recounts night of fatal I-94 crash, through tears," May 1).

It is possible that she was being as honest as she could be given the limitations of her conscious brain to remember something it was most likely never conscious of. Without reading Kahneman's book, very few of us are aware of how quickly System 1 does its work to come with up with an explanation outside our conscious awareness, in our "continuous attempt to make sense of the world."

The jury seemed to interpret her inability to remember the night's events as a sign she might be lying about at least some aspects of the case.

One of the jurors, Jay Larson, told the Star Tribune after the verdict: "It was almost like from the moment she got up from the day of the crash, she remembers where she went that morning, she remembers taking the kids to the mall, she remembers everything. How would she remember everything so well it's almost versed, but come to that time of the crash, there's just ... we just couldn't buy it anymore."

Another juror wrote in a May 12 commentary ("The thinking of the jury on the Amy Senser case") that Senser "also should have been more forthcoming in court."

Yet Kahneman offers this remarkable insight from which we can form a possible explanation as to why Senser had so much trouble remembering the events of the evening of Aug. 23, 2011: "A general limitation of the human mind is its imperfect ability to reconstruct past states of knowledge, or beliefs that have changed. Once you adopt a new view of the world (or of any part of it) you immediately lose much of your ability to recall what you used to believe before your mind changed."

As for why Senser avoided hitting Phanthavong's vehicle, even though it partially straddled the white line defining the driving lane of the exit ramp and she didn't recall seeing it, consider this from Kahneman: "System 1 can respond to impressions of events of which System 2 is unaware. Indeed, the mere exposure effect is actually stronger for stimuli that the individual never consciously sees."

By looking at a picture of the scene that night, it is easier to understand how the bright reflection of the construction signs might have minimized Senser's ability to see the less-bright flashing hazard lights on Phanthavong's car. In addition, she testified that as she drove up the exit ramp, she was looking at the bridge to her left to see if it was the right one.

Because of the efficiency of System 1, and the inability of System 2 to multitask, it is possible that when she got to the top of the exit ramp and realized it was going to be far more complicated to return to St. Paul than she anticipated, she put the question of what caused the sound out of her mind.

Her System 1 had already created an explanation -- it was a pothole, her most common experience. (Remember: System 1 "is not designed to know the size of its jumps.")

It is only when she got home and was able to inspect the damage to her car that her System 1 and System 2 were forced to work together to create a different explanation for the sound -- that she hit a construction barrel or sign, objects that she remembered seeing that night.

• • •

I offer this possible explanation with a caveat: I am not Amy Senser, so I have no idea what she saw that night, what she thought she hit at the moment she heard the sound, or why she didn't stop. None of us do.

This is why the task of the jury -- to try to determine what she did see, what she thought she hit, if she fled in panic or ignorance, and if she was lying or telling the only truth she knew -- was essentially an impossible one.

Jurors were further hampered by the influences of priming and outcome bias, and thus, without conscious awareness, admittedly shifted their focus from a question that was impossible to answer -- "What did Senser know?" -- to a question that was easier to answer: "What would a reasonable person do?"

Kahneman writes: "When faced with a difficult question, we often answer an easier one instead, usually without noticing the substitution."

Answering the question, though, of "what a reasonable person would do" allows for introduction of the experiences and opinions and perspectives of each individual juror into the deliberation process, undermining the credibility of a verdict that should be based only on the facts and evidence presented in the case.

Cultural influences cannot be checked at the courthouse door. We are immersed in a culture of distrust. Several national political leaders have tried to suppress the truth about their personal indiscretions. Logical conclusion: Everyone lies when they're guilty.

Combine these influences in the stew of the jurors' minds: cultural influence, prosecution's "out for blood" approach, outcome bias -- the knowledge that someone was killed, the high-profile aspect of the case, the belief that accountability is equivalent to justice.

What you get is an overwhelming sense of responsibility to send the correct message -- to future defendants of hit-and-run accidents, to the victim's family, to society at large.

Sending a note to the judge ("Jurors' note to judge: We believed Senser didn't know she hit a person," May 10) before the verdict was announced could have been the jury's way of splitting the difference, saying essentially: "Yes, we understand our responsibility, but we also want Amy Senser to know we don't think she knew she hit a person."

Frankly, learning about the note was a relief. A clean guilty verdict seemed too heartless a punishment for the failure of the conscious mind to remember something it was most likely never conscious of.

--------------

Ellen Hoerle is a writer in Eden Prairie. She holds a master's degree in public policy from the Humphrey School of Public Affairs and just started blogging at at www.yesiampayingattention.com.