Before all the recent headlines about United Airlines fade in our memories, it's time to take another look at them. A lot of "bad publicity" is how news reports repeatedly described United's problems. Case in point was the "PR disaster" reference about United in the Star Tribune's Business section on April 19. But the incidents with United are not bad PR. Quite the opposite. Communication between the organization and the public worked exactly as it should have. It's important for all of us, from CEOs to consumers, and everyone in between, to understand how public relations works, since we encounter it on a daily basis. To characterize United's experiences as bad PR ignores the value of interactive communication.

A brief review of what brought United into the headlines: First there was the no-leggings dress code enforced for young daughters of employees flying for free. Then the incident where an elderly passenger, forced to give up his seat, was dragged, bloodied and bruised, off the plane. Finally, United gained more headlines when a passenger was stung by a scorpion during a flight. There are three key points to understand how these situations illustrate the good of public relations:

1) United Airlines' problems were not public relations problems; they were operational ones that lacked adequate communicator involvement or influence.

These incidents, while not entirely predictable, happen regularly enough that organizations make contingency plans in case something happens. It's a process in which operations and communications staff work together to identify and plan to manage issues with potential problems. Picture yourself as a communicator for United. In a meeting with executives, you hear the chief operations officer report that oversold flights have risen sharply in the past year due to a number of factors. You know about the policy to pay for volunteers to give up their seats.

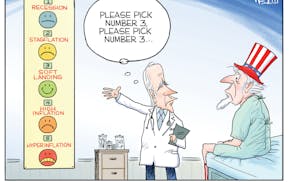

Part of your job in PR is to think about worst-case scenarios. So you ask about what happens when no one volunteers, and everyone is already seated on the plane. The COO responds, "Then we call in security and have some passengers forcibly removed from the plane." At this point, you would apply what PR practitioners call "the grandma test." It is to be able to explain the issue to your grandma so she understands and accepts it. Grandma does not need to be a relative, or even female, just someone who is slightly skeptical and supremely wise. If you asked grandma about the no-leggings dress code, she would probably agree. But any version of communication about the "involuntary denial of boarding" process would fail; grandma would raise her eyebrows and say, "Oh, I don't know about that."

For companies to avoid their own version of a "forced deplaning" debacle requires that there are enough communicators involved in contingency planning, with influence to change processes that fail the grandma test.

2) Public relations means relations with publics.

The news label of "bad PR" has been applied to these incidents based on how they affected United Airlines, the company. It ignores the other side of the equation, in the benefits for the public. The passengers took action to communicate, and their communication was highly effective. The social-media posts got immediate response from United, and the attention of stockholders. The interactive communication resulted in an apology and hopefully better treatment for future United customers. It's also a benefit to the companies, in having real-time, immediate communication. No delay in knowing what happened on the plane.

The United incidents also show that organizations need to communicate with a broader range of people. To date, the response from United Airlines has been a promise to improve its customer relations. But it's not just customers who engaged in this communication. Executives may be biased by their MBA or marketing perspective, which views PR's value as promotional, to support sales. You have to be able to see the forest beyond the trees, and communicate with the general public that determines United's reputation.

3) The irony of free speech.

One of the strongest public reactions to the forcible deplaning incident came from hundreds of millions of Chinese commenting on Weibo, the Chinese version of Twitter, angry about the treatment of the passenger, who was Chinese-American. The global reach of the communication could have been expected, since United has frequent daily flights to and from China.

Ironically, had the United incident occurred on a Chinese airline, in China, no one would have posted to the internet a video about a passenger being forcibly removed from the plane. To do so would be risking the wrath of the Communist government. No one in the U.S. would call free speech a PR disaster.

A final point about the irony of free speech is passengers on oversold airplanes now know the value of their seats. Delta Air Lines made headlines by saying it would now be willing to pay up to $10,000 to get passengers to voluntarily give up their seat. All this good PR means passengers can negotiate higher prices to stay off the plane.

Maureen Schriner, of Eagan, is leaving her faculty position as a professor in public relations and advertising at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire in May to return to working full-time in public relations.