What was going on in your Facebook news feed the week of Jan. 11-18, 2012?

Birthday reminders, cat videos, crockpot recipes, baby pictures and invitations to play Bejeweled Blitz, probably, plus lots of current events posts were guaranteed to make you glad or mad.

That week, Mitt Romney won New Hampshire's Republican primary, Playboy announced it was leaving Chicago, and Hostess filed for bankruptcy, prompting fears that there would be no more Twinkies. The Patriots knocked the Broncos out of the NFL playoffs, putting an end to Tebowmania. Chicago had its first real snowfall in an otherwise mild winter, Derrick Rose was out with a sprained toe, and your crazy cousin was picking fights with anyone who commented on any of it.

If you were one of nearly 700,000 randomly selected Facebook users, though, your feed might have contained a little less to "like." Or dislike. For years, Facebook has ignored pleas to add a clickable thumbs-down icon. Maybe this is why.

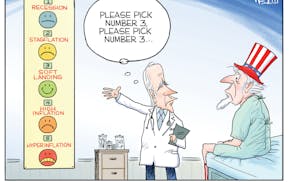

That week, Facebook conducted a little experiment. Its robots trolled the news feeds of the users in that sample, tinkered with them to reduce the number of positive or negative posts, then studied the users' own entries for signs of "emotional contagion." They wanted to see if reducing the positives (or negatives) in your news feed made you feel less positive (or negative).

The results were published in the June 17 issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study suggests that yes, emotional states can be transferred via social media, with no face-to-face interaction or nonverbal cues. People with happier news feeds posted slightly happier things themselves; people with grouchier feeds wrote slightly grouchier posts. The more conclusive finding, though, is that Facebook users don't appreciate being treated like lab rats.

There's nothing new about Facebook messing with the content supplied by its half-billion users.

Its ever-changing algorithm determines which of your friends' posts appear in your feed and where. Currently, the algorithm seems to dictate that every time someone "likes" a photo you "liked" previously, then that photo must rocket to the top of your feed again. That forces you to scroll past it over and over and over, because it's not quite annoying enough to make you log off, which means you're wasting even more time on Facebook than you used to. That's not an accident.

Periodically, Facebook provokes a fresh uproar by rearranging the elements on users' home or personal pages, seemingly on whim, or changing the rules about who can see what. Where are your videos this time? Where did these ads come from, and how did Facebook know you were shopping for underwear yesterday? Keeping your privacy settings updated can feel like a losing battle, but those BuzzFeed quizzes are kind of addictive, like everything else on Facebook. So you keep threatening to close your account, but you don't.

The truth is that the whole Internet is one giant experiment in user behavior, though generally the goal is to figure out how to sell you something rather than to make you smile or frown. You might not like it, but you're getting used to it.

But Facebook's research crossed a line. This time, it wasn't just manipulating users' content; it was manipulating their minds. And without permission. Yes, you agreed to Facebook's terms of service and no, you probably didn't read them. So legally, Facebook has done nothing wrong. But ethically? It's a real stretch to argue that clicking on a little box the day you joined Facebook constitutes informed consent all these years later.

Talk about emotional contagion. Facebook made several thousand people happy or sad — and millions of them furious. But somehow we don't expect a mass exodus. Because where does everyone go to rail about this outrage? To Facebook, that's where.