BEMIDJI, Minn. – Refugee resettlement will not be allowed in Beltrami County, where officials voted late Tuesday to deny consent under an executive order from President Donald Trump that places the decision in the hands of local governments.

The vote was largely symbolic — no refugees have been resettled in this county for at least five years — but it appears to be the first move by a county board in Minnesota, and one of few nationally, to close a county to newly arriving refugees.

The 3-2 vote came on a day when the contentious issue surfaced in counties across the state, including St. Louis County, where Duluth is located, and Stearns County, home to St. Cloud. In both counties, officials postponed decisions on the matter despite a looming deadline.

"I think we will be making history today," said Beltrami County Commissioner Reed Olson, who voted in favor of refugee resettlement.

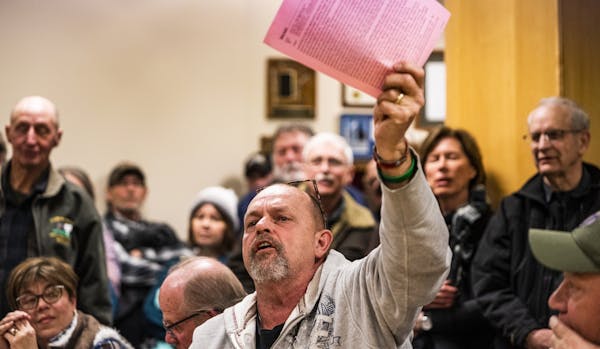

The audience applauded as the resolution passed during an unruly meeting filled with jeers, shouts and accusations among the more than 150 people — most of them opposed to allowing refugees — packing the county chambers.

Trump issued the executive order in September requiring consent from local officials before any refugees would be resettled in their communities.

Gov. Tim Walz, a DFLer who has spoken out against Trump's immigration policies, submitted a letter in December consenting to refugees being resettled in the state, and North Dakota Gov. Doug Burgum, a Republican in a state with high presidential approval ratings, also recently gave approval for refugee resettlement as long as local governments consented.

Asked for comment on the Beltrami County vote Tuesday night, Walz said, "I'm disappointed. But I understood that this executive order was meant to be divisive. … It should have never been [pushed] down to the county levels."

But across the nation, county officials are wrestling with the issue as a Jan. 21 deadline approaches. Burleigh County, N.D., which includes the city of Bismarck, voted 3-2 to limit refugee resettlement to no more than 25 people in 2020. Appomattox County in Virginia went further and refused refugee resettlement.

Whether jurisdictions such as Beltrami County will make any difference in the real fate of refugee resettlement is unclear. Minnesota's five resettlement agencies have solicited letters of consent from about two dozen counties in Minnesota that have a record of taking in refugees as they prepare to submit plans for the coming year. Those decisions take effect June 1.

More than a dozen counties have already submitted letters of consent. Hennepin and Dakota counties were among those that agreed Tuesday to welcome refugees. Ramsey County has resettled the largest number of refugees in the last five years (4,215), followed by Hennepin (1,345), Stearns (662), Anoka (430) and Olmsted counties (377).

If local jurisdictions take no action by the deadline, refugees may not be placed there. But the law applies only to the initial settlement of refugees; those already settled in the United States can move anywhere they wish.

The Beltrami County vote came as a mystery to Bob Oehrig, executive director of Arrive Ministries, one of Minnesota's refugee resettlement agencies. "That's not a county that's really had any refugee resettlement. … I don't know what they'd be voting for or against," he said.

At an October rally in Minneapolis, Trump's supporters cheered when he mentioned the local-consent order. Addressing the crowd at Target Center, he noted Minnesota's large number of Somali refugees and said, "You should be able to decide what is best for your own cities and your own neighborhoods."

But heated debate on the issue vexed county leaders across Minnesota on Tuesday as they faced meeting rooms packed with constituents who wanted a say on the matter.

At the courthouse in Duluth, more than 40 people testified over 2½ hours before the County Board voted 4-3 to postpone action on the measure. Many represented faith groups and spoke of European ancestors immigrating to the United States in search of better lives, urging their commissioners to open the county so others could do the same.

"I think this is the critical moral issue of our time," said Brooks Anderson, a retired pastor from Duluth.

Others called on county leaders to oppose the resolution, some saying that refugees would be a burden on taxpayers, schools and law enforcement.

"We don't have the resources," said Gerald Williams, of Virginia. "We can't take care of our own people. We don't take care of our own people."

No one with refugee status has been settled in St. Louis County, the state's largest county by area, in the last five years, the Minnesota Department of Human Services said.

"This executive order is about dividing county and states," said St. Louis County Commissioner Patrick Boyle, whose district includes part of Duluth. He wanted to approve the resolution Tuesday but was overruled by his fellow commissioners who want more time to consider what the implications of a letter of consent would be.

In St. Cloud, where immigration has become a political flash point in recent years, the Stearns County Board postponed action on a request from refugee resettlement agencies for a letter of consent.

Commissioner Steve Notch said he still had too many unanswered questions and wanted to hear from the public and other experts. He lamented equating humanitarian concerns with economic ones.

Commissioner Joe Perske said it was "imperative" that the county decide the issue immediately. "The question I hear today is, are we a welcoming community or not?"

But Commissioner Leigh Lenzmeier insisted that the commissioners need more information. "I don't see the hurry," he said.

In Beltrami County, Commissioner Craig Gaasvig began the meeting by asking for a show of hands from people who oppose refugee resettlement. When most hands went up, he said, "Thank you for showing up and showing us that."

Many opponents voiced concern that the county could not financially support refugees; some said refugees brought problems to St. Cloud and they didn't want them to play out in the Bemidji area too.

But Magie Baumgartner of Bemidji said after the meeting that opposition to refugees was heartbreaking and called the vote a "national shame."

Commissioner Tim Sumner, a member of Red Lake Nation, also voted to give consent for refugee resettlement.

"A lot of people that migrated here are resettlers, so it was difficult for me to understand how a resettler can tell another resettler, 'Well, you're not welcome here,' " he said. "I guess in my beliefs and thinking, that's not appropriate."

Staff writers Dan Browning, Rochelle Olson, Erin Adler and Stephen Montemayor contributed to this report.

Man agrees to 6-year sentence for fatally shooting Hopkins man on edge of downtown Minneapolis

Softball coach, with record delayed but not denied, keeps winning

Ludacris and T-Pain to stand up together at Minnesota State Fair grandstand in 2024

13-year sentence for man who fatally hit other driver while fleeing police in Oakdale