Attorneys for Winona County and a sand mining company clashed in court Thursday over the legality of Minnesota's first countywide ban on frac sand mining.

Saying the county's two-year-old ban is unconstitutional and an illegal "taking" of a private property owner's rights, attorney Christopher Dolan for Minnesota Sands argued before the state Court of Appeals that the ban should be overturned.

Dolan and an attorney for Winona County were rigorously questioned by the three-judge panel about the company's claims of constitutional violations, the difference between frac sand mining and mining for construction sand, and why Winona authorities didn't simply put a cap on mining rather than prohibit all of it.

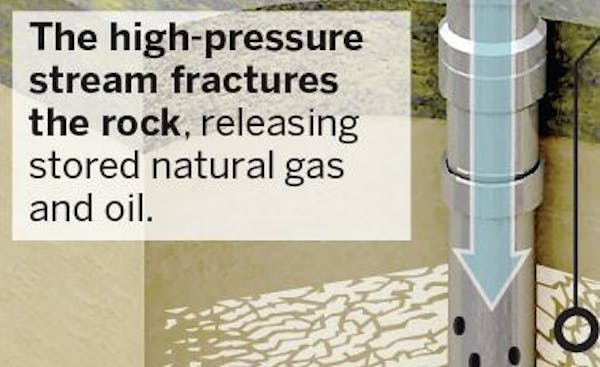

Dolan said the company worked for years to acquire mineral rights in areas of Winona County rich with silica sand, a material of enormous value for oil field fracking operations used to prop open cracks in shale rock while extracting natural gas. The county's ban, passed by a 3-2 vote in 2016 as an amendment to the local zoning ordinance, "eviscerated" the value of those leases, Dolan told the court.

The company sued the county, but in November, Winona District Judge Mary Leahy ruled that the county was within its rights to regulate frac sand mining and dismissed the company's claims.

Dolan began Thursday's hearing in St. Paul by saying the district court committed four errors in its decision, but the Appeals Court justices cut him off soon after he got underway.

Appeals Court Judge Lucinda Jesson first took issue with the company's claim that the frac-sand ban was a violation of the Constitution's commerce clause.

"I just don't see that here," she said.

Dolan countered that it was a hoarding of the sand, something that the commerce clause would prohibit.

But Appeals Court Judge Renee Worke asked if there were any local uses for frac sand, also known as industrial sand; a local use could justify hoarding it for future use. But the frac sand mines operating throughout Minnesota and Wisconsin mostly send the industrial sand by rail to oil fields in Texas and elsewhere.

The judges then began to hone in on another of the company's arguments — that the mining process for frac sand and construction sand are the same.

The Winona County Board has allowed mining to continue for construction sand, a cheaper and less pure material that's used on roadways and for other commercial purposes. Minnesota Sands has argued that Winona's ban discriminates against its business because it specifies that only industrial sand mining is prohibited.

A report from the state Environmental Quality Board found that there are significant differences in mining the two sand types, most of them driven by the need for industrial sand grains to be of a particular size, shape, purity and intactness. Filtering out unwanted grains requires water and a chemical flocculent, some of which can get pumped back into the ground with the unwanted sand. The demand for industrial sand also follows boom and bust cycles that can at times greatly outweigh the demand for construction sand, with varying levels of trucking as a result.

Jesson asked if Dolan if he was trying to say that the processes are identical.

Dolan maintained there's disagreement over that point, saying Minnesota Sands takes the position that silica sand is so pure in Winona County that it needs little processing, eliminating the differences in its mining compared with construction sand.

Judge Matthew Johnson asked Dolan if the silica sand could be used for all of the local purposes that construction sand typically gets used for. Dolan said it could.

The judges then moved on to the argument by Minnesota Sands that Winona County took something of value from them and didn't provide compensation as required by law. That, too, fell under heavy scrutiny as the appeals panel questioned whether Minnesota Sands had a vested interest in the property.

Attorney Jay Squires, arguing for Winona County, said the company never had a right to mine, and thus can't prove its argument, because it never completed an environmental-impact statement as required by the state Environmental Quality Board. Without that permit, there is no right to mine, he said.

Johnson asked if the county could have regulated the sand mining through a cap of some kind, limiting the amount of silica sand mining but not prohibiting all of it. Squires said the county examined alternatives to a ban but ultimately determined that whether there was one mine or 10, the risks posed to local geology, water and roadways were unacceptable.

"It is our belief," Minnesota Sands said in a statement issued after the appeals court hearing, "the Winona County's zoning ordinance amendment was adopted to keep Minnesota Sands and other similar operators from being able to mine silica and at a broader level also eliminates landowner mineral rights."

The ban is a "significant threat" to landowners, the letter added, saying it could lead to future unconstitutional restrictions on land use.

The Appeals Court has 90 days to issue its ruling.

Demand for frac sand has soared to record highs, with some 100 million tons needed this year, according to a Rystad Energy analyst. The northern white sand from Minnesota and Wisconsin is considered the best in the industry, but also the most expensive. Texas oil producers have been developing their own sand mines that produce lower quality but far cheaper sand.

8 months in jail for Blaine man who caused 120-mph crash hours after he was caught speeding

Daughter sues St. Paul, two officers in Yia Xiong's killing