Is writing the word "ISIS" on a Muslim student group's sign an act of free speech? Or hate speech?

What about the phrase "Make rapists and racists afraid" in front of a fraternity house?

Those are the kinds of questions the University of Minnesota has been wrestling with for the past year, since it created a "bias response team" to monitor acts of bigotry on the Twin Cities campus.

So far, the team has fielded almost 100 reports of so-called bias incidents since February 2016. Along with a wave of complaints about swastikas and racist graffiti, some students have raised alarms about professors using stereotypes of Asians and gays in classroom discussions. About Facebook posts and overheard conversations. About a group of students hitting a President Trump piñata.

University officials readily admit that what some see as bigotry, others see as the First Amendment in action. But they say the Bias Response and Referral Network is doing its best to walk that fine line.

"We need the network as a place for all of us to go when we experience, see or hear biased behavior," President Eric Kaler said in a March speech. "We need to promote a culture that honors free speech while discouraging hateful words."

The problem, critics say, is that free speech is often the first victim when bias response teams appear on campus.

"At some point, it is policing what people are saying," said Amna Khalid, an assistant professor of history at Carleton College in Northfield. Instead of encouraging students to confront opposing views, she says, it turns them into informants. "No matter how well-intentioned these committees may be, what they end up doing is really infantilizing our students," she said.

In February, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) warned that bias response teams are an emerging threat on college campuses. In a survey of more than 230 colleges, it found that students and faculty have been reported for such "protected speech" as satirizing "safe spaces," referring to the police as "terrorists" at a public rally; and leading a class discussion about transgender rights.

"Just having a team on campus might make some people think twice about addressing touchy subjects," said Adam Steinbaugh, the chief author of the report. "Because who wants to sit there with an administrator or someone from HR and say, 'No, I was playing Devil's Advocate'?"

U officials say they've seen no evidence of a chilling effect. "We have actually found that it's had quite the opposite impact," says Kris Lockhart, the associate vice president for equity and diversity, who helps oversee the group.

U: Team brings consistency

Before the team was formed, she notes, the same kinds of reports would arrive scattershot throughout the campus, and there was little coordination on how to respond. Now, she says, "we can act more efficiently and consistently."

In all, the bias network has 19 members across the university. But Ann Freeman, one of the leaders, said that the group has no authority to investigate or discipline anyone.

"Our role is really more educational and referral than it is direct action," said Freeman, who is also a consultant in university relations. The team's main job, she said, is to consult with other departments, such as university police, on how to respond, and offer support to those who feel victimized.

Benjie Kaplan, executive director of Minnesota Hillel, is a fan. "I really believe this network is fantastic," said Kaplan, who worked closely with the group this year after a string of anti-Semitic incidents. In February, when Nazi graffiti was found in a Jewish student's dorm room, the bias team helped ensure that the threat was taken seriously, Kaplan said, and that the U publicly condemned the incident. "When your community is under attack, you always feel like there should be more done," Kaplan said. "But I think they are doing great work."

At the same time, some faculty members worry about the unintended consequences, especially when people can file complaints anonymously.

'Room for mischief'

"There is room for mischief here," said Jane Kirtley, a professor of media ethics and law at the U. "This is a really good way for disgruntled students to try to get their professors in trouble." Last fall, she recalled, a student sent her an e-mail complaining about her use of the term "undocumented aliens" in class. Kirtley said she explained that she was merely quoting a specific statute. But even so, the "whole semester I was wondering if I was going to get a call from the bias response team."

In response to faculty concerns about academic freedom, the U added two professors to the team, including one with expertise in free speech. It even changed its name, originally the "Bias Response Team," to sound less like a "SWAT team," Lockhart said.

As the newly dubbed Bias Response and Referral Network, officials said, it doesn't hesitate to push back when people complain that they're offended by an act of free speech.

In practice, though, records from the past year suggest that the U's response isn't always consistent on that score.

On Feb. 10, a student complained about white supremacist fliers, and was told that the U "doesn't censor postings that follow our posting policy, even when they are contrary to our values," according to the bias incident log. Yet one week later, the log shows, an "extremely anti-Semitic flier" was reported outside McNamara Alumni Center, and U police promptly removed it.

U officials could not explain the distinction, but said other factors may have been at play — such as rules governing postings, graffiti or destruction of property.

'Better than many,' but …

On paper, the U's bias response policy "is better than many," says Steinbaugh, who wrote the FIRE report. Unlike most schools, he said, it explicitly requires those who assess bias complaints to factor in free speech. But in practice, he says, that may not pan out.

"There are definitely situations where they have done the right thing," said Steinbaugh, who reviewed the U's log at the Star Tribune's request. "But a lot of this seems to be pretty clearly protected speech."

The incident log sometimes only hints at what happened.

In December, a staffer complained about "a loud conversation" in which three student-athletes reportedly said "disparaging things" about women's sports. The response: "This information was sent to Athletics, and the department will follow up."

In February, a student complained about a group of students hitting a piñata of President Trump in Coffman Union. After noting that the bias group doesn't focus on political incidents, the report was forwarded to the Student Unions and Activities office "to determine whether any policies were violated."

To Steinbaugh, that's troubling. "It's not very helpful to essentially think, 'Well, this is protected speech, but we're going to refer this on to another department and let them deal with it,' " he said.

U officials say they're not passing the buck, but they forward bias reports to other departments to keep them informed. They say the U may still have a role to play, even if no policies or laws are broken.

"Even sometimes when it is free speech, people are affected," said Lockhart. When a gay student encounters homophobia, she said, "it impacts their ability to walk on campus, to go to class and to get an education."

To Khalid, the Carleton professor, the problem is that bias teams can affect education. "Nothing quite kills intellectual exploration like the fear of causing offense," she and Jeffrey Snyder wrote in a 2016 essay in the New Republic.

That's especially toxic in a classroom, says Snyder, also an assistant professor at Carleton. "Something like race becomes so charged that we're afraid to say anything about it," he said.

Lockhart, though, says there's no sign that's happening at the U. "I think we've had a more thoughtful dialogue across the university about bias, about campus climate, about free speech and about academic freedom."

Maura Lerner • 612-673-7384

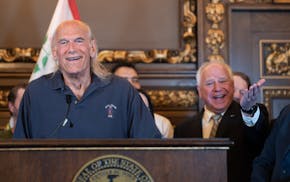

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president

Dave Kleis says he won't run for sixth term as St. Cloud mayor

Newspaper boxes repurposed as 'Save a Life' naloxone dispensaries

St. Cloud house vies for Ugliest House in America