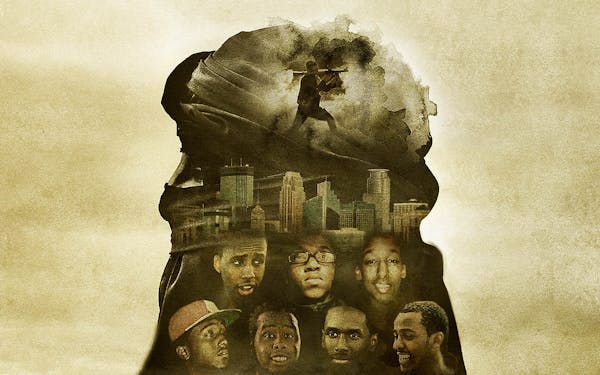

Federal prosecutors in Minneapolis will pull back the curtain this week on one of the nation's largest terrorism recruitment cases, as three young Somali-American men go to trial on charges that they conspired to join the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and commit murder abroad.

The trial caps a yearslong FBI investigation into a circle of friends from Minnesota's Somali-American community and may offer a glimpse inside the minds of young Americans drawn to the call of radical jihad. It promises to be a lengthy trial attended by many members of the Twin Cities' Somali community, the nation's largest.

And because it is only the third federal ISIL-related case to come to trial, it will also be closely watched across the country for clues on how the government can detect and prosecute potential homegrown terrorists — something that has trained a global spotlight on Minnesota.

"New York has seen more arrests, but Minneapolis' recruits are tied together in a way we've not seen before," said Seamus Hughes, deputy director of the George Washington University Program on Extremism, which has tracked the 86 ISIL-related cases charged since 2014. "You wouldn't have seen 15 people [try to] go out of Minneapolis-St. Paul if they didn't know each other."

Of the original group, six have pleaded guilty and one made it abroad. Several others also left for Syria in 2014 and have since been killed in battle.

The final three have resolved to fight the government's case, with their families insisting they are innocent.

Abdirahman Daud, 22, has been described as a gifted athlete who wanted to be a dental technician. But he was arrested with another defendant after trying to cross into Mexico last year.

Mohamed Farah, 22, aspired to be a teacher; he shuttled his six siblings to school, tutored them and did the family's grocery shopping. But he was caught on tape saying he would kill any FBI agents who got in his way.

Guled Omar, 21, was a pre-nursing student who liked watching "The Office." But he allegedly tried to follow his fugitive older brother, who joined Al-Shabab, before setting his own sights on ISIL.

When jury selection starts Monday — after a hearing on one attorney's late request to leave the case — they will face charges that could put them in prison for life.

The men were among 10 charged in a federal investigation whose roots can be traced to the disappearance nearly a decade ago of several Minnesotans who left for Somalia to join Al-Shabab. Among them was a Roosevelt High grad who in 2008 became the first American suicide bomber overseas.

By 2012, agents working on the FBI's "Operation Rhino" began following a group of friends using surveillance and an informant culled from their circle to record their activities.

At his plea hearing last month, Mohamed Farah's younger brother, Adnan, 20, shed light on how ISIL appealed to the group of young Somali-Americans.

"Looking back at it, what would you say is the hook that grabs teenagers? That grabbed you?" U.S. District Judge Michael Davis asked.

"[ISIL's] propaganda is based on the battle of hearts and minds," said Farah, who estimated that he watched at least 100 ISIL-produced videos. He said they made him want to join the group's fight against Syrian President Bashar Assad, known for ferocious suppression of Muslim opposition groups.

"They believe that once you control someone's heart, and you have them attracted to this or in love with this, you can control their minds," Farah said. "And I would say I was attracted to it, and I felt like it was the right thing to do."

A series of failed attempts to flee in 2014 — efforts foiled by either family intervention or FBI interdiction — only added fuel to the group's desire to leave, according to court documents. They followed a blueprint that had worked for others — taking a bus to New York City and trying to board flights to Europe with stops in Turkey, which shares a border with Syria. Others drove to San Diego and tried to cross into Mexico and fly overseas.

The case has sown division within the Somali-American community and intensified debate over how to combat radicalization without stigmatizing one community.

"We see this as a defining moment," said Sadik Warfa, a community leader who has served as a spokesman for some defendants' families. "We have to make sure this kind of story doesn't define who we are. … We are bigger than this."

Other Somali-American leaders have spent much of the last year helping their community understand a complex legal process.

"You never have the community on the same page," said Mohamud Noor, whose Confederation of Somali Community was one of six organizations funded as part of a federal pilot project to fight terror recruitment through social services. "There are groups who say take it all the way to trial until proven guilty, and others say if there's any shred of evidence you should take a deal."

One measure of the attention on the case is that the federal building's largest courtroom has been packed with relatives and supporters for most pretrial hearings, requiring overflow seating and a thick law enforcement presence.

Despite the gravity of the charges and months of pretrial maneuvering, the parents of the remaining defendants still say they are confused by the case — and insist on their sons' innocence. "This is manufactured and this is not true," Fadumo Hussein, Omar's mother, said recently. "They never left, they didn't kill anybody, they didn't harm anybody. Why are they in jail?"

The FBI's use of an informant has also rankled some, including a growing contingent of antiwar and civil liberties advocates who say the defendants were entrapped.

The government's key witness is Abdirahman Bashiir, 20, who was present at many of the group's planning meetings as a co-conspirator. By early 2015 he was a paid informant who flipped after lying to agents and a grand jury. At defendants' plea hearings, however, after questioning from Davis, each has said they weren't entrapped because they were willing to carry out the plot before Bashiir turned informant.

Davis, who has presided over every Minnesota terror recruit case since the Al-Shabab episodes, has signaled a deliberate approach that balances the gravity of a federal terrorism case against the youth of the defendants.

Since last year, Davis has experimented with alternatives to jail and introduced the country's first "deradicalization and disengagement" program to compile better information before he considers sentencing. As part of that program, German counterterrorism expert Daniel Koehler interviewed five defendants and their families last month.

"I can say that their radicalization processes did not differ significantly from what I have seen in other countries," said Koehler. "In fact, they were by-the-book radicalization processes."

In pretrial hearings, Davis has asked if the young men understood the proceedings and demanded that they give more than yes-or-no answers.

And on the eve of the trial, he is also in a position to set the tone for other cases to follow. Late last year, for example, when prosecutors added charges of conspiring to murder abroad, Davis denied a defense motion to drop the charge on grounds of "combatant immunity," which argued that ISIL was an army engaged in traditional warfare.

Then last month, when Daud's attorney, Bruce Nestor, asked for a jury instruction that the men may have thought they were traveling overseas to fight in defense of others, he drew an animated reply from Davis.

"I'm shutting the door on this," Davis said. " …This is not a political trial."

Stephen Montemayor • 612-673-1755

Twitter: @smontemayor

Israel-Hamas war creates 'really fraught times' at Minn. colleges

Rare and fatal brain disease in two deer hunters heightens concerns about CWD

911 transcript gives more detail of Sen. Mitchell's alleged burglary

Police arrest man suspected of invading St. Paul home, raping and robbing woman