FORT MYERS, FLA. — Once the entire Twins squad assembles on Wednesday morning for the first full team workout, the days will end around 12:30 p.m. -- except next Thursday, when the players will be let out early to take part in their annual charity golf tournament.

It has been the Twins' way going back to Tom Kelly. They get their work in and have afternoons to themselves.

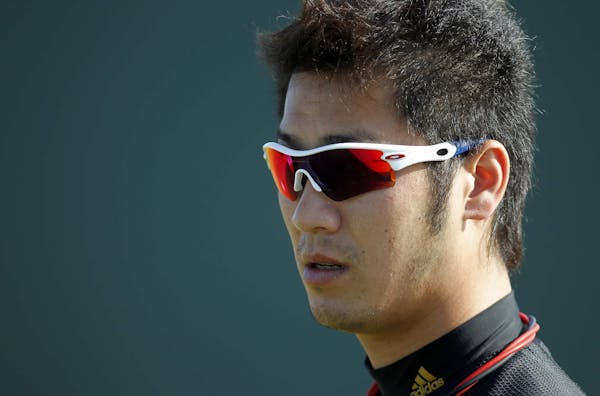

That's not how it's done in Japan. Tsuyoshi Nishioka, the Twins' new middle infielder, is about to find out the differences. And now that the Twins have become the 27th team in the majors to employ a player from the Japanese Leagues, so will the team and its followers.

Nishioka's arrival opens a new chapter in Twins history -- and opens a door to baseball in the Far East, where the game offers a peek into the culture.

Where Nishioka comes from, a workday means working on your game until 6 p.m. -- and there might be night practices. And then you return to your hotel room at the end of the day, not a vacation home or condo. The Japanese don't know any other way than to prepare, prepare and prepare some more. The approach is rooted in martial arts, with "endless training, development of spirit, self-sacrifice, etc.," author Robert Whiting, who wrote a popular book on Japanese baseball called "You Gotta Have Wa," said in an e-mail.

"The samurai code of Bushido and the martial arts philosophy were grafted onto the game in the late 19th century," Whiting said. "For the Japanese -- in the pros, high school and college -- baseball is a year-round endeavor. High school baseball players in the big schools get New Year's off, that is it. The rest is practice. Total dedication."

Driven by history

American professor Horace Wilson introduced baseball to Japan in the late 1870s while teaching at what is now Tokyo Imperial University. The sport became a hit on the high school and college levels. And the first professional team was born in 1935.

By the time baseball became a professional sport in Japan, routines were established that continue today.

There are stories of intense training sessions in the past in which players pushed on despite welts and bruises from being hit with batted and pitched baseballs.

Training sessions today entail a lot of repetition -- things unheard of in the major leagues.

"The first thing that jumped out at me was the practice time guys put in," C.J. Nitkowski, a lefthander who pitched for eight major league teams before joining the SoftBank Hawks in 2007 and '08, wrote in an e-mail. "At spring training I would see young players arriving the team hotel from spring training workouts at 7 p.m. after our day started at 10 a.m. They would eat dinner and then go to 'swing practice' at the hotel, 500 dry swings. Pitchers would do similar routines.

"I've seen 250-pitch bullpens before, which in American eyes is absurd. Guys will practice this hard, see guys get hurt and continue to do the same routines. They know one way, work hard, work long."

Former Twins outfielder Michael Restovich, a Rochester native who played in Japan in 2008, said American players didn't have to practice as long as Japanese players. They would return to the team hotel and be eating dinner when other teammates were arriving from workouts.

He said Japanese players would miss a ground ball, then bow to the coaches to apologize. The next ground ball would be farther away from him, the next one even farther. The player would dive and dive and dive, his jersey layered with dirt.

"There are so many things about what the Twins do that make them so successful," said Restovich, who played for the Twins from 2002 to '04. "I remember the quote. 'Let's do things right. We're not going to be here all day.' Over there, there's no sense of whether you are doing it right or wrong. They obviously want it done right, but there's a definitely a sense that no matter how it goes, we're going to be here until 5, 5 or 6."

While speaking to a reporter on Feb. 4, Nishioka seemed eager to begin his season.

"This is not too early," he said through interpreter Toru Suzuki. "Japan has already started spring training. This is when I start, in February."

Spring training in Japan began on Feb. 1, with the regular season starting March 25. Nishioka isn't used to inactivity. Japanese reporters who stopped by the Lee County Sports Complex last week indicated that Nishioka was in a rush to get started.

Rooting interests

American baseball fans like well-pitched games and good defense. They also like home runs.

Howard Norsetter, the Twins' international scouting coordinator who has been traveling to Japan since 1998, believes the opposite is true in Japan.

"I think it's almost as if they would rather get a guy on base, bunt him over to second, hit behind and get him over to third and then hit a sacrifice fly," Norsetter said. "That's a better run than a home run to them."

It's born of "groupism," a Japanese viewpoint that values the many over any individual. And that sort of rooting is part of a large investment made by fans in Japan. There are cheer squads at every game. Every player has a song. Japan has several daily baseball newspapers. The high school championships are similar to the Final Four in men's college basketball here.

"Roll up the Final Four and Indiana high school basketball and Minnesota high school hockey and the Super Bowl and the World Series and you are getting close," Norsetter said.

Nishioka left all that to test his game in the major leagues, where he doesn't speak the predominant language and will play for a team that never had a player from Japan before him.

An unenlightened reporter speculated in a recent blog that it might help Nishioka if the Twins added another Japanese player to help with the transition. Because the Twins needed bullpen help, he speculated on free agent Kenshin Kawakami.

Within minutes, a Japanese reporter responded that it would add even more pressure on Nishioka, because he would have to respect Kawakami and be obligated to join him for dinner and take on other responsibilities.

Whiting confirmed the sempai-kohai (senior-junior) relationship.

"Younger players are expected to be subservient to their seniors," Whiting wrote, "Even if their field performance is superior, show them respect, deference. Call him Kawakami-san. Light his cigarettes, etc."

So Nishioka will have to go it alone, bringing the game he has learned through more hours or work than most American baseball players can even imagine, hoping his style of play will help the Twins be successful.

"I expect the Twins to win another pennant," Nishioka said, "and to help."

Jets beat Canucks 4-2 in the regular-season finale for the playoff-bound teams