It wasn't the first, nor was it the biggest.

But Target's data breach struck a nerve like no other.

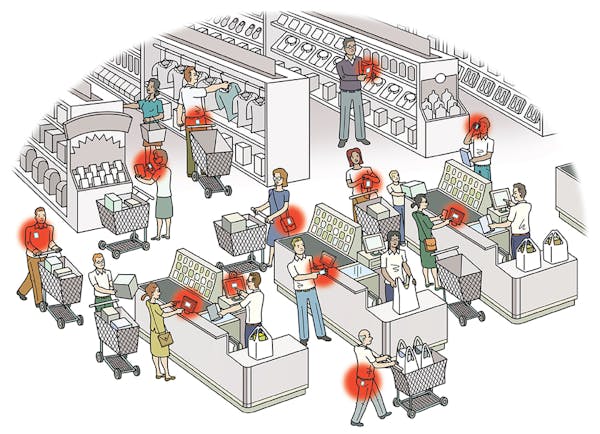

A year ago this week, cyberthieves started copying information from every transaction at Target's 1,800 U.S. stores. After they were stopped three weeks later, the heist made international headlines and scared customers away from Target at the peak of the Christmas shopping season.

In the weeks that followed, Target's sales and profits sank, executives were grilled by Congress and, in May, chief executive Gregg Steinhafel was ousted.

A year later, a lot has changed.

More than a dozen other major retailers and service providers — from Dairy Queen to Neiman Marcus — have endured similar cyberattacks. The firms, banks and credit card issuers have largely insulated consumers from harm, rendering such breaches far less scary than Target's seemed at the time. Meanwhile, a cross-industry effort to create safer credit cards and debit cards is making progress. And Target itself is more or less back to normal, with its executives just this past week forecasting a stronger holiday season.

None of that seemed likely a year ago, when the Minneapolis-based retailer found itself at the center of consumer fears, intense media scrutiny and the mockery of late-night TV comics.

"The roulette ball came up on Target," said Charlie O'Shea, an analyst with Moody's Investors Service. "It's not as much of a shock as it was before."

Breach fatigue

The cyberattack on Target was the biggest on a major U.S. retailer since one on T.J. Maxx in 2007. But since Target was hit, cyberthieves have attacked so many consumer-facing companies, including Home Depot, JP Morgan and the U.S. Postal Service, that a new catchphrase has set in: breach fatigue.

"You don't see alerts and news articles written about (other breaches) every five minutes like Target did," said Sean Naughton, an analyst with Piper Jaffray.

Even so, 69 percent of Americans in a recent Gallup survey said they worry about having credit card information lifted by hackers. And about 19 percent of shoppers in a National Retail Federation survey said that data breaches would likely affect where they shop or how they pay this holiday season.

Retailers' sales figures paint a different picture. Cyberthieves collected financial data from more customers in the Home Depot breach disclosed two months ago than in Target's, but customers hardly blinked. Home Depot last week reported its sales jumped 5.4 percent in the August-to-October quarter, outperforming many other retailers.

"Consumers quickly forget about these breaches," said Avivah Litan, a security analyst with research firm Gartner.

In addition to being the first big firm hit in several years, Target suffered because its breach came to light at the worst possible time for a retailer, during the week before Christmas. Not only is it the busiest time of the year in retail, but media attention on shopping is high and shoppers are anxious to finish their holiday tasks. "There's a lot of stress going on that time of year," said Amy Koo, an analyst with Kantar Retail.

Target, banks and other credit card issuers promised to protect Target's customers from damage if stolen credit card information led to fraudulent charges on their accounts. Many customers asked for new cards to be issued, a practice that has been repeated as other breaches occurred.

"The real disaster has been for retailers and banks. They're on guard," Litan said. "They're reissuing cards much more aggressively. There's a lot more replacement cards going out in the mail than there used to be."

New cards

The breach at Target triggered an industry discussion about upgrading the U.S. credit payment system to cards that are more secure than ones in which the data is encoded on magnetic stripes. In much of Europe and Asia, credit and debit cards have computer chips that hold more data and hide it in code that's hard to decipher.

Even before the Target breach, the U.S. payment network industry had set a deadline of October 2015 after which the liability for breaches would transfer to retailers if they hadn't switched over to the more secure payment systems, called EMV cards.

But many people thought that date would be pushed back because not enough companies would be ready in time, said Martin Ferenczi, president of the U.S. division of Oberthur Technologies, a supplier of chip-based cards. Following the breach at Target and other places, it's now clear that date will stand.

"There's no doubt that the sense of urgency changed dramatically after the breaches," Ferenczi said.

New cards will begin showing up in consumer mailboxes next year, and card issuers estimate that one out of every two cards in the U.S. will have chips in them by the end of next year.

After the breach, Target decided to speed up its $100 million plan to update its terminals to accept EMV cards. Those card readers were installed in all stores by September and will be activated early next year. The retailer also plans to reissue its RedCards, the credit and debit cards it manages and that provide discounted shopping, with chips.

Wal-Mart already has terminals in its stores that can accept chip-based cards. Home Depot says it will accept them next year.

Target's turnaround

When Target confirmed that its point-of-sale system had been hacked, it initially said 40 million credit and debit cards were compromised. It later revealed that 70 million shoppers also had their personal information hijacked.

Traffic at its stores plunged, leading the firm to announce a weekend promotion of 10 percent off everything just before Christmas. As the breach made front-page headlines, TV comics zeroed in on the news. "A company spokesman said 'Maybe we shouldn't have named ourselves Target,' " Conan O'Brien joked the day after Target revealed the trouble.

As it tried to win shoppers back, Target continued to sprinkle the stores with deep discounts over the following months. Store traffic has rebounded every quarter since and was down just 0.4 percent in the most recent quarter, ending Nov. 1.

"We still have work to do to heal the U.S. business," John Mulligan, the company's chief financial officer said last week. He added that executives believe customers had mostly shrugged off the breach by the middle of the summer. "We feel we moved past the breach, much more quickly than perhaps those who write about us."

A longer-lasting change at Target has been the shake-up at its headquarters in downtown Minneapolis. The breach came amid other difficulties, including struggles with its digital strategy and a botched, too-fast expansion in Canada that was producing hundreds of millions in losses each quarter. The combination of those troubles led Target's board to remove Steinhafel and hire Brian Cornell, a former PepsiCo and Wal-Mart executive, as new chief executive. The firm also replaced its chief information officer and hired its first chief information security officer.

Target's costs related to the breach haven't panned out to be as bad as initially feared. Some analysts forecast that the retailer would have to spend $1 billion to fix its systems and pay damages to customers and banks. So far, Target has reported about $248 million in breach-related costs, about $90 million of which is expected to be covered by insurance. By comparison, Target has lost about $1.6 billion with the flailing expansion in Canada.

Painful and public as it was, the breach forced Target's leaders and board to re-evaluate its entire business and the ways in which it had been losing ground.

"It kick-started them a little faster," Koo said.

Kavita Kumar • 612-673-4113