The Minneapolis police stopped fewer suspicious people, suspicious vehicles and traffic scofflaws than usual over the past year, a change that in some neighborhoods resulted in police stops falling by about half.

Police made about 66,000 of the stops, which do not include 911 calls for help, citywide in the first six months of last year. It's fallen to about 44,000 for the first half of this year, city data show. The shift has not fallen evenly across the city, and in some places the diminished police activity has been more acute: stops for traffic violations downtown have fallen by 53 percent.

Asked why the numbers are dropping, Chief Janeé Harteau pointed to the department's 784 sworn officers, its lowest staffing level in at least 10 years. She also said the drop reflects a change in crime-fighting strategies that she argued doesn't show up in the stats.

"I don't want traffic stops just for the sake of traffic stops," she said in an interview.

Harteau said she's changed officers' priorities since she took over the department 18 months ago, and argued that some of those changes have meant officers "engage with the community" rather than conduct stops.

She pointed to officers walking a beat or attending a community meeting. They might also spend more time on a burglary call or a report of a gun being fired, she said.

"That's proactive work. It's not being counted," she said.

The stops are those done spontaneously by officers on routine patrol. They might see a car without a license plate or working headlights and decide to pull it over. Or they might see someone walking in a suspicious manner and decide to stop and talk to him or her.

Harteau said she plans to hire new recruits and experienced officers from other departments to push the force's numbers up to 860 officers by year's end. A pension rule change this year drove more officers than usual into retirement, and the aging department has already seen its roster fall below 800 sworn officers.

The falling stops tally has also given rise to union concerns that overworked officers don't have time to do their jobs.

'Tight, limited resources'

The city has recorded three types of police stops for years: a stop for a suspicious person, a suspicious vehicle or a traffic law violation. The information gets printed up each week in the department's weekly crime statistics and compared to past trends. The effort, known as CODEFOR in Minneapolis, was introduced in the 1990s as data-driven "hot spot" policing became more common across the country.

In south Minneapolis, where robberies are up 41 percent so far this year, violent crime is up 23 percent and burglaries are up 20 percent, the number of police stops are down by 30 percent. Becky Timm, the executive director of the Powderhorn Park Neighborhood Association, said a recent meeting with police officials about shots fired in Powderhorn Park resulted in a police promise to send more officers to patrol the park when they're not tied down with 911 calls.

"I'm sure they're just like everyone else with such tight, limited resources," said Timm.

Patrol stops attack

The patrols that do work E. Lake Street sometimes find urgent need for their presence: On a recent patrol, officers saw three men surround and then attack a fourth man with knives near the corner of Lake Street and 1st Avenue S. The officers came up unseen behind the knife-wielding assailants, and were able to capture all three, according to court papers describing criminal charges. The victim was stabbed several times in the left arm but escaped the ordeal with minor injuries thanks to the officers' intervention.

More typically, police officers make a stop when they see something that doesn't look right, like a car being driven at night down an alley with its headlights off, said Lt. John Delmonico, president of the police union.

It's not happening as often now simply because the department is stretched too thin, said Delmonico. "I think the most obvious thing is less cops," he said.

He said he spoke to three police officers this week about the falloff in stops and all three pointed to the smaller staff. "We don't have the people, and we don't have the time," he said they told him.

The frustration for police, Delmonico said, is that independent stops by a patrolling officer are considered a cornerstone of police work. Investigating a suspicious person or stopping a car that looks out of place can lead to criminals who might otherwise get away, he said.

It's not unusual for a traffic stop to find someone who's wanted on a warrant or who's carrying drugs, he said.

"Is less traffic stops a correlation to crime going up? It could be," said Delmonico.

Watchful neighbors

Violent crime has risen 4 percent in Minneapolis so far this year. That's on top of a 4 percent rise in violent crime last year, though police officials quickly point out that crime remains at historic lows when compared to crime rates of the 1990s.

Longfellow Community Council executive director Melanie Majors said residents in her neighborhood have been concerned about the rise in robbery and burglary in south Minneapolis.

A neighborhood meeting earlier this year drew a few dozen locals to hear from top police officials, she said.

"They didn't say that they were dropping down on these stops or anything but they did say they were concentrating their efforts at Lake and Hiawatha. It actually makes a difference," she said. "We all know there's less police but I do think they prioritize based on crime statistics."

People were told to call 911 if they see something suspicious, and the community council printed up lawn signs that carried the same message.

"People really are starting to pay attention," she said.

Matt McKinney • 612-217-1747

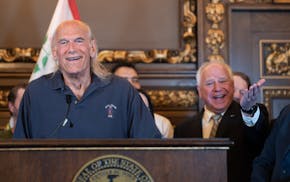

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president

Dave Kleis says he won't run for sixth term as St. Cloud mayor

Newspaper boxes repurposed as 'Save a Life' naloxone dispensaries

St. Cloud house vies for Ugliest House in America