It underwrote AIDS prevention in the 1980s when many funders were still leery, launched provocative ad campaigns to foster awareness of discrimination in the 1990s, raised seed money for the now-vibrant Minnesota Women's Foundation, and poured about $850 million into the Minneapolis area over the years.

Now the Minneapolis Foundation is celebrating its 100th anniversary, marking its place in history as one of the world's oldest community foundations.

On Monday, the foundation kicked off the first of several events scheduled to showcase its support for anti-poverty initiatives, the arts, health care and more. Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges was on hand at a news conference to declare "Minneapolis Foundation Century Day," speaking alongside an art project commissioned in the IDS Center courtyard depicting the Minneapolis of the future.

"To give you an idea of how far we've come in 100 years, I'd like to share these numbers," said Sandra Vargas, foundation CEO. "During the foundation's first year of operation, we distributed $25,000 in grants — a stark contrast from last year's $47 million."

In 1915, a group of five Twin Cities businessmen came up with an idea to support their fast-growing city.

Why not encourage its wealthier residents to donate to a community fund that would pool the cash, invest it, and give some of its earnings to improve Minneapolis?

The concept of a "community foundation" was new. The first one had been launched in Cincinnati a year earlier.

Minneapolis joined the fledgling philanthropic movement, which has grown to more than 1,800 community foundations across the globe.

Steady growth

The Minneapolis Foundation now distributes earnings from 1,200 charitable funds set up by individuals, families and businesses, to the tune of nearly $40 million last year.

It also gives grants from roughly $7 million in other funds and manages $735 million in assets.

Raising funds, awareness

The foundation operated out of First National Bank for decades, with a board of directors that included some of Minneapolis' best-known families, said former foundation CEO Marion Etzwiler.

In 1970, it hired its first executive director, Russ Ewald, who set up an office in the Foshay Tower and began raising its profile and giving. Its purse strings opened significantly by the early 1990s, when Etzwiler reported that she had raised its assets from $27 million to more than $150 million.

The late 1990s brought Emmett Carson, a CEO who wasn't afraid of brash public relations campaigns.

When then-Gov. Jesse Ventura's administration, for example, proposed freezing new government contracts with nonprofits, the foundation launched a powerful ad campaign, said Jon Pratt, executive director of the Minnesota Council of Nonprofits.

The ad included a photo of a forlorn young girl holding a sign saying, "If we cut funding for nonprofits, will you let me come to your house after school?"

"It wasn't just about raising money, but raising challenging questions for the community," recalled Carson, now CEO of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation.

Vargas became just its sixth CEO in 2007, continuing many existing priorities such as closing gaps in educational attainment, wages and housing, as well as promoting civic engagement.

In a nod to the priorities of younger donors, the foundation is increasingly funding environmental issues.

Its work has always been a reflection of the era. In 1973, it awarded its then-biggest grant — $130,000 — to help desegregate three Minneapolis junior high schools.

In the 1990s, it was a staunch advocate for early childhood education and all-day kindergarten.

More recently, it supported tornado cleanup on the North Side and provided loans to help minority-owned businesses participate in the construction of the Vikings stadium.

It also has been in the vanguard of developing new philanthropists with its "Fourth Generation" project for young professionals, as well as with programs for immigrant groups learning the ABCs of philanthropic legacies.

Lessons learned

Like most community foundations, this one has its challenges, its leaders acknowledge.

It's been a scrappier philanthropy, willing to try new approaches to long-standing problems. That's been a mixed blessing.

For example, one of its highest-profile projects, Destination 2010, provided educational support to 364 third-graders starting in 2001 through high school and was prepared to give them $10,000 apiece for college if they graduated.

By graduation deadline 2010, just one-third had stuck with the program, and fewer were prepared for college.

The lesson: "Unless the education system changes, those individuals and families can't override the system," said Vargas.

Carson said the foundation has historically been a "bridge builder" — on one side, informing Minneapolis residents about things they might not want to know about their community, but also proposing solutions for those problems.

"The challenge for community foundations is to be at both ends," Carson said.

Pratt said the foundation has long been a friend to nonprofits.

But he notes that community foundations now face growing competition for donor charity funds from for-profit financial institutions.

The foundation's leaders, past and present, agree that Minneapolis was fertile ground for launching such a pioneering idea in philanthropy — and that bodes well for the next 100 years.

"It took thousands of generous Minnesotans, nonprofits and local leaders to build this incredible place we call home," said Vargas. "The history of the Minneapolis Foundation is really the story of our whole community."

Jean Hopfensperger • 612-673-4511

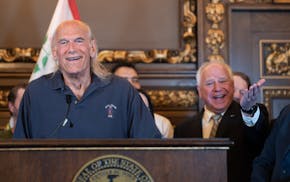

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president

Dave Kleis says he won't run for sixth term as St. Cloud mayor

Newspaper boxes repurposed as 'Save a Life' naloxone dispensaries

St. Cloud house vies for Ugliest House in America