Nekima Levy-Pounds wants to be voters' first choice for Minneapolis mayor, but she's not deterred if someone professes support for one of her opponents.

For those who can't be swayed, she tries a different pitch: How about a second-choice vote? Or even marking Levy-Pounds down third?

"Those numbers are going to add up and ultimately determine the winner of this election," she said. "People are going to have to study their second choice and their third choice just as much as they study their first choice."

The state's two largest cities will each elect a mayor in November, and candidates in the midst of heated campaigns are simultaneously courting votes and providing a little tutelage on the relatively new ranked-choice voting system. St. Paul is picking a new leader from a crowded field of 10 candidates, and in Minneapolis, one-term incumbent Betsy Hodges is running against 15 challengers.

Voters in both cities are no longer limited to one choice, and that's changed the tactics candidates are employing. Some are hesitant to criticize others for fear of alienating their supporters. Both cities have had the ranked-choice system for less than a decade, and voters and campaigns are still figuring out how to navigate an election where people can list their preferences. Fans of the new system say it encourages broader participation, but critics say it is confusing.

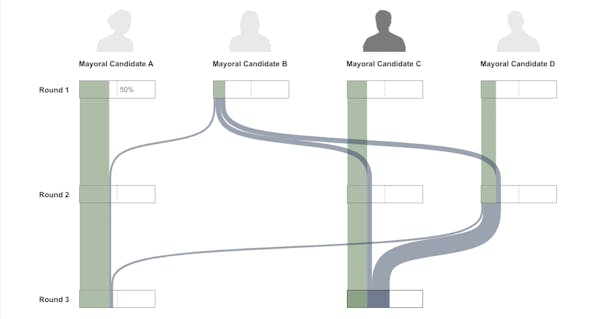

FairVote, an organization that supports ranked-choice voting, has staff or informational brochures at almost every political event in the two cities to explain the system, which eliminates candidates who get the fewest votes and reallocates votes until one of the candidates has a majority.

The brochures, tucked into programs at mayoral forums, tell Minneapolis voters they will be ranking not only their top three mayoral choices on Nov. 7, but also their choices for City Council, Park and Recreation Board and Board of Estimate and Taxation. St. Paul voters will be ranking only mayoral candidates, and they can choose up to six.

That means more studying for voters like Ella Thayer, who lives on St. Paul's West Side. When the city made the switch, she didn't like it. At that time, she only knew her first choice. But the idea of listing multiple preferences has grown on her, she said as she settled into a seat at a mayoral forum last week for some more research.

Candidates and campaign staff said this is the first true test of how the voting system shapes the competition in a St. Paul mayor's race. The 2013 mayor's race was ranked, but incumbent Chris Coleman ran with minimal opposition and won in a landslide.

"There's so much to be learned from this election once the results are in," St. Paul candidate Dai Thao said.

Reducing negativity?

When Minneapolis voters first used the new method of voting in 2009, it was lauded by supporters as a way to bring a diversity of voices into the election process and reduce negative campaigning.

Ranked-choice voting does bring more people and ideas into a race, but having an incumbent in the mix changes the dynamics, said Hodges' campaign spokeswoman, Alex West Steinman.

"When you have a very collaborative leader who's an incumbent they're more likely to get attacked by others who want to unseat that person," she said.

Minneapolis candidates have become increasingly critical of their opponents as Election Day nears.

"It's difficult to win a race against an incumbent without pointing out how you would do things different," said Joe Radinovich, campaign manager for candidate Jacob Frey. "Contrasting in a focused way is something you really have to do."

In St. Paul, where there's no incumbent running, the majority of candidates are avoiding blatant attacks on their opponents, at least so far. Minneapolis mayoral hopefuls were similarly hesitant to criticize others four years ago when they were competing for the seat R.T. Rybak vacated, said Roann Cramer, who was vice chairwoman of the Minneapolis DFL during that election.

"This year there's been some coalescing against the incumbent," said Cramer, who supports Hodges.

In San Francisco, where ranked-choice voting has determined municipal elections for 14 years, political analyst David Latterman said incumbents have fared well. Ranked voting allows a crowded field of candidates and people default to the incumbent because they have name recognition, he said. Challengers generally fare best if they go after the incumbent as if it were a traditional one-on-one race, he said.

"If you go down the rabbit hole of thinking about that demographic's second choices, and that group's third choices — therein lies madness," Latterman said. "It's better to just run your race."

Twin Cities voters have noted moments when candidates seem to be angling for people's second choice.

When Thao recently announced his opposition to St. Paul's controversial Ford site rezoning plan, critics said he was trying to get the runner-up votes of Highland Park residents who disliked the plan, many of whom support Pat Harris as their first choice.

Thao, who is on the City Council, said he was trying to reach a compromise with residents who felt the city was ignoring their concerns.

Opponents remain

Not all residents are sold on the new way of voting, which eliminates primaries and allows all candidates to end up on the final ballot.

In St. Paul, it will result in a long process after Election Day. Election officials will use an electronic system to redistribute Minneapolis residents' choices and the winner will likely be announced Nov. 8, the day after the election. In St. Paul, however, ballots will be hand counted and the final results will likely not be known until Nov. 11.

A small group of St. Paul residents urged the city's Charter Commission earlier this year to eliminate the ranked system and return to primaries. Shawn Towle, who was behind that push, said he's taking the issue to the Legislature this year and hopes it will pass a bill blocking use of the system statewide.

"There's this feel-good notion that, 'Oh, you have more choices,' " he said, but with so many candidates it's hard to have a comprehensive understanding of their positions. Opponents also said it was confusing, cost too much and did not increase voter turnout.

Many voters said that the ranked system is too new in St. Paul to determine its effectiveness and that this election will provide a critical test. It was used in City Council races in 2011 and 2015, but not a contentious citywide election.

Minneapolis and St. Paul are the only Minnesota cities that have made the switch to a ranked-choice system. But others, such as St. Louis Park, are looking into it — and watching how the Twin Cities' elections unfold.

Jessie Van Berkel • 612-673-4649

New police chief in Columbia Heights will start work Friday

An infamous heist put this North Woods town in the global spotlight. Nervous breakdowns and Hollywood deals ensued.

Lotto America player in Minnesota hits $3.1M jackpot

Star Tribune adds Kavita Kumar, Melissa Wind to news organization's leadership