Going, going, gone: Macy's is pulling the plug on the Store Formerly Known as Dayton's.

Sometime in March, the last standing department store in downtown Minneapolis will be history. It's a sad and probably inevitable denouement to 700 Nicollet. But let's set aside any discussion of the Oval Room, the eighth-floor auditorium shows, the Daisy Sale and other beloved retailing legacies. This is a restaurant requiem.

That's because the store boasts a proud 113-year dining history, one that should be celebrated. (The restaurants close on Jan. 27.)

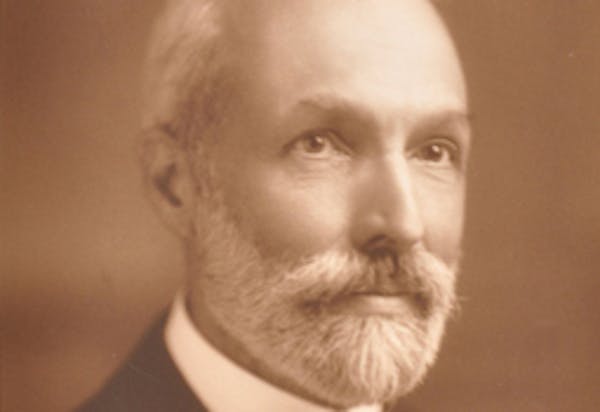

It began in 1904. Two years after founder George Draper Dayton opened the store that eventually bore his name, a restaurant opened on the fourth floor. In the period's parlance, it was called a tearoom, and shoppers arrived, in droves.

Expansion yielded newer, larger food-and-drink destinations, eventually culminating in the 12th floor's fraternal twins. Their original names were the Men's Oak Grill and the Sky Room, and both were key players in a burst of postwar optimism, a multimillion-dollar expansion that elevated Dayton's into the fraternity of the nation's 10 largest department stores.

True, other Dayton-driven innovations were just down the road.

In 1956, Southdale, the nation's first enclosed shopping mall, would open in Edina, forever changing the way America shopped. The transformation of the nation's retail landscape continued six years later, when the company launched its first Target store in Roseville. Today, the discounter, the nation's second-largest retailer, operates nearly 1,800 outlets. In 1966, Dayton's debuted B. Dalton, a bookseller that became a familiar name across the country; it was sold to Barnes & Noble in 1987.

But the 1947 addition was an investment that cemented the store's supremacy on the state's retail landscape. And what a lasting legacy: The two restaurants (a third, the Tiffin, a casual but stylish cafeteria, fizzled in the 1960s) have lived long after the Dayton's name was pulled from the building in 2001, replaced first by Marshall Field's, and then, five years later, by Macy's.

A dining refuge

Perhaps we owe Macy's our gratitude for not messing with these last vestiges of our Dayton's.

Contemporary shoppers unfamiliar with the store's storied pre-Macy's life can't really grasp the lifelong affection and regard that shoppers held for the two massive mismatched brown buildings that stretch across an entire city block on Nicollet Mall.

Former Minneapolis Star columnist Jim Klobuchar summed it up best. "If you couldn't find it at Dayton's, either it didn't exist or it wasn't available," he wrote in 1979.

During the Macy's years, the store's retail floors slowly receded into a shadow of their former selves, a painful death by a thousand paper cuts and indignities. But the restaurants? Take a seat in the Oak Grill today, and it feels as if the Macy's era never happened.

"A poor man's Minneapolis Club" is how the Oak Grill's cigars-and-brandy ambience was captured in a 1970s Minneapolis Star article. Perfect, right?

It's restaurant as stage set: The white oak paneling, the heavy furniture, the crisp white linens, the flickering fireplace (an intricately carved, solid oak beauty, salvaged from a Jacobean manor in southern England shortly after World War II) and the dim lighting all contribute to the room's reassuringly stolid sense of calm.

Ditto the menu, which echoes the room's comfort-food past with well executed chicken pot pies, classic Minnesota wild rice soup, meatloaf with peppery gravy and mashed potatoes, almond-crusted walleye and a chicken salad made with what is surely the city's last appearance of the water chestnut. And, of course, popovers.

Brilliant cuisine? No. But suitable to its surroundings, and pleasing.

It's a credit to Warren Wolfe, group vice president of Macy's food services, that the Oak Grill's reassuring sense of timelessness has never faltered. The restaurant's service staff also deserves high marks for its warmth and professionalism, which hark back to a time when "Dayton's" was synonymous with "quality."

There's just so much Minneapolis history in this room. Did the dynamic, forward-thinking Dayton brothers — Bruce, Donald, Wallace, Kenneth and Douglas, grandsons of founder George Draper Dayton — dream up Target, and the Dales, and B. Dalton while lunching in front of that fireplace? Who knows? But it's a lovely thought.

Room with a view

If the Oak Grill was inward looking and overtly masculine, its massive next-door neighbor, the Sky Room, was the complete opposite.

It's hard to imagine now, but the restaurant wasn't always today's bright, loud, utilitarian Salad Bar in the Sky. Hardly. In its original incarnation (and two-word name), the Sky Room was designed to be Dayton's ultimate loyalty-building machine.

Beyond its day-to-day function as a female-friendly luncheon destination, and through a steady diet of fashion shows, club gatherings, charity dinner-dances, Santa breakfasts and other events, the coolly elegant Sky Room was a deluxe component in cultivating steadfast shopping habits. Like the tearooms that preceded it, the Sky Room was designed to get women into the building and keep them there, spending money. And making memories.

The strategy worked, for years. Here's a measure of Dayton's market supremacy: In the pre-McDonald's era, several thousand people a day dined at Dayton's.

(It's telling that when Macy's opened its Mall of America outlet in 1992, a store executive looked with awe at the grip that Dayton's had on the Twin Cities market. "We are facing an institution that has been here a long, long time and earned their stripes," he told the Star Tribune. Yeah, no kidding.)

Robert Hansen, the store's University of Minnesota-trained in-house architect, used all kinds of design tricks to give the enormous Sky Room a glamorous sweep, with floor-to-ceiling Thermopane windows, a curvaceous ceiling, lush draperies, dramatic state-of-the-art lighting and eight magnificent Waterford chandeliers. It was the store's open-to-the-public penthouse, and it was an instant hit.

"The new tearoom, decorated in the modern manner with slate gray walls and white ceiling with indirect lighting, provided a swank background for the elegant fashions modeled by league members," was how the Minneapolis Tribune described a Junior League fashion show that was staged for 800 guests on the evening of Oct. 1, 1947, the night before the restaurant opened to the public. (Husbands were invited to attend the dress rehearsal, held the previous day.)

In its own advertising in the late 1940s, Dayton's cannily trumpeted its Sky Room as the "Showplace of the Northwest" and "One of America's smartest achievements in dining."

The press agreed. "The Sky Room has no equal in the United States as far as a restaurant of this type goes," raved Virginia Stafford of the Minneapolis Tribune in July 1949. "Right now I could drool thinking about that special fresh lobster Thermidor that became a real adventure in lunching there, not so long ago."

A major selling point — and novelty — was the panoramic views. Remember, this was a time when the 32-story Foshay Tower dominated the skyline.

"See Minneapolis through walls of glass," boasted one early 1950s ad, which also pointed out that breaded pork tenderloin or scalloped salmon, served with dessert and a beverage, cost $1. Another from the same period — this time, aimed at budget-conscious shoppers — extolled the restaurant's built-in chic, noting that a suit's "rich wool gabardine is dressy enough for Sky Room dining."

It should be noted that the Sky Room played host to many celebrities over the years, including actresses Rosalind Russell, Joan Fontaine, Jane Russell, Constance Bennett, Helen Hayes, Ruth Gordon and Mary Martin, as well as singer Dionne Warwick, author Betty Friedan and fashion designers Claire McCardell, Adele Simpson and James Galanos.

Bowing to changing demographics and shopping patterns (women were entering the workforce in record numbers, and the ones who weren't were shopping in the suburbs at the Dales), the Sky Room took a radical turn in the 1970s.

The ladies-who-lunch vibe disappeared, and the restaurant targeted the busy downtown lunch crowd, lured to the 12th floor (via an express elevator) with a well-stocked salad bar.

The room also got a makeover. Inexplicably, the glorious chandeliers were placed in storage (four later materialized on the store's first floor, part of a remake of the cosmetics department) and the decade's earth tones took over.

A 1987 renovation introduced the white-on-white color palette that exists today. Several quick-service counters also made their debut, along with a new, single-word name: Skyroom.

It may no longer be the native habitat of the the city's socialites, but hundreds of diners continue to drop into the 300-seat Skyroom on weekdays, lured by its 40-foot salad bar ($2 in 1978, $9.95 today) and five busy quick-service cafe counters.

Beyond restaurants

In 1913, Dayton's figured out that one way to reach a shopper's heart was through her sweet tooth.

"Our own candy kitchen" is how the ad hailed the newcomer (peanut brittle cost 25 cents a pound) and the in-store operation kept Minnesotans in chocolate, nuts and assorted nougats for the next century.

Boxes of Cossack Mints ("Yummy, creamy with minty chocolate all the way through and coated with smooth, rich chocolate," reads a 1953 ad) were big sellers from the 1930s into the early 1970s.

The story behind the Cossack name is a mystery. But in the 1970s, "Cossack" gave way to Minnehaha Mints and, in the 1980s, Boundary Waters Mints.

When the company purchased Marshall Field's in 1990, the Chicago store's trademark Frango Mints became the marquee name at Dayton's, and the candy kitchens — tucked away from view on the building's 12th floor — began producing specialty Frango flavors.

Another food tie: Unlike his father George Draper Dayton, George Nelson Dayton's career initially took a different path. Out of college he established and then sold a farm in Anoka County, and in 1926, while he was running the store, purchased an 800-acre spread on Lake Minnetonka's Smithtown Bay and named it Boulder Bridge Farm.

For the next 24 years — until his death in 1950, when the farm was sold — Dayton (Gov. Mark Dayton's grandfather) managed what became a nationally famous herd of purebred Guernsey cows.

The farm had one customer — Dayton's — and the 200-head herd's milk and cream was channeled to the store's restaurants, where it was served in specially marked glass bottles and hailed on menus. This was no hobby. In 1949, the farm's output was 900,000 pounds of milk; that's roughly 105,000 gallons.

The store's food-related innovations continued long after the Dayton family took the company public in the late 1960s. In 1984, the store's bargain basement was replaced by revamped housewares departments and Marketplace (now Signature Kitchen), an instantly popular food hall that included a bakery, deli, candy counter, gourmet foods shop, a quick-service branch of Leeann Chin, a cafe called 700 Express and a trendy gourmet cookies counter called Le Petit Gateau.

Ironically, the remake borrowed elements from (and improved upon) the Cellar, an earlier reincarnation of the basement at Macy's store on Union Square in San Francisco.

Looking ahead

While the loss of the city's last department store is cause for concern and lament, Macy's exit also presents a rare opportunity to rethink and reposition a major downtown asset.

(How major? Huge. The sum of the square footage — two basements and 12 above-ground stories — is just shy of Southdale's entire leasable space.)

Given the building's history, here's hoping that food plays a significant role in whatever developer 601W has in mind.

It's not such an out-there proposition, because food-centric remakes of historic department stores are certainly on the rise in other American cities.

Because of its proximate size to Dayton's, the project to watch is the rebirth of the longtime home of the May Co. in downtown Los Angeles. The 1908 Beaux-Arts behemoth is currently being refashioned into offices, a hotel with a rooftop park, a food hall, restaurants, bars, a private club, parking and retail.

In 2015, a massive 1925 Sears store and warehouse in Atlanta (twice the size of 700 Nicollet) became the Ponce City Market.

It's primarily a mix of housing and offices, but its centerpiece is the Central Food Hall. A larger, more upscale version of the Midtown Global Market — another Sears store remake, at Chicago and Lake in Minneapolis — it features nearly 30 cafes, restaurants, bakeries, food vendors and bars, led by some of the region's top chefs and restaurateurs, including four James Beard award winners.

In Birmingham, Ala., the elegant Pizitz department store is undergoing a $70 million conversion into housing, offices, three restaurants and a food hall with nearly two dozen stalls. The building, which dates to 1923, is less than a quarter the size of Dayton's.

The former Hahne & Co. in downtown Newark, N.J., has just been reborn as housing, a cultural center for Rutgers University, a Barnes & Noble bookstore and the city's first Whole Foods store; a Marcus Samuelsson restaurant is on its way. The 1911 building is roughly a third the size of Dayton's.

The stately Filene's in downtown Boston? Its first floor and basement — yes, that basement — is now Roche Bros., a gourmet supermarket.

Oh, and while Uber is planning to house several thousand employees in the upper floors of the former Capwell's in downtown Oakland, Calif., the main floor is being reserved for a food hall grocery, Newberry Market.

Please, 601W, imagine the possibilities, and think big. The Skyroom as a red-carpet-worthy cocktail palace. The main floor as the crossroads-of-the-city food hall. The skyway level as downtown's see-and-be-seen lunch destination.

In the thinking-small department, there's always the example of the tearoom at L.S. Ayres. A decade after the Dayton's of Indianapolis closed in the early 1990s, its restaurant's elegant setting was recaptured — from furniture to fixtures to beloved menu items such as "chicken velvet soup" — in the nearby Indiana State Museum.

It's now used for private events, and comes to life as a restaurant every year during the holidays, giving Indianapolitans young and old a festive taste of the long-gone niceties of gracious department store living.

Treat the Oak Grill like some kind of art museum period room, installed, perhaps, as a dining destination inside the Minneapolis Institute of Art? It's a thought.

If we'll never have Dayton's again, at least we could still have its signature restaurant, or a facsimile thereof. And, if we're lucky, a popover.

Rick Nelson • 612-673-4757